Introduction

In histories of specific places in the Black Country, the first paragraph often begin in a similar way to that of (1) with regard to West Bromwich.

“Of the pre-conquest history of West Bromwich, we know practically nothing.”

There are a number of reasons for this lack of knowledge, but perhaps the main one is that much of the evidence of the remote past has been destroyed in the rush to industrialisation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. That being said, I want to show in this blog, that by considering evidence from a wide variety of sources over the entire region, it is possible to say something about the pre-Domesday history of the area, even if only in the broadest outline.

I will look at the material that exists chronologically – the stone ages, bronze age, iron age, the Roman period and the Anglo-Saxon period, before looking in a little more depth at the Domesday record itself. But we begin by defining an area of study.

Defining the Black Country before it was black.

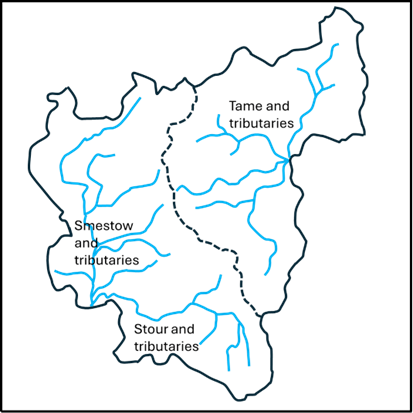

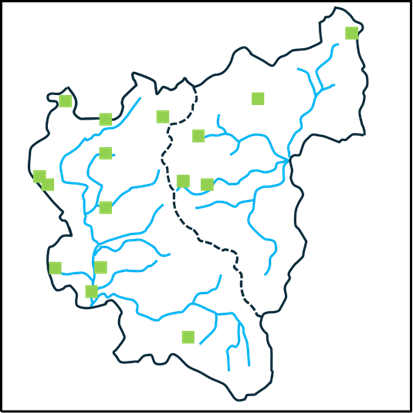

The first question that arises is what area we should consider? The concept of the Black Country as such is of course a creation of the 19th century, and even today, there is no consensus on its extent. Some would argue that it is confined to the area of the South Staffordshire coalfield, others that it is the area of the current boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton. The status of places around its periphery are argued over endlessly (and vehemently). The only consensus is that Birmingham isn’t part of it. But none of these definitions are of relevance to the period before Domesday, when the area was wholly rural. So, in what follows, I have chosen major natural features to define the area of interest – basically the catchments of the upper Stour and Smestow, and of the headwaters of the Tame. These are shown in Figures 1a and 1b, with the former identifying the rivers and the latter showing the position of the major modern towns in the area. The catchment maps are taken from (2) and (3). It should be noted, that as with everything else in the Black Country, the precise locations of the streams shown in these figures owe a great deal to human activity and may well have been different in the periods we are considering. The boundary between the two catchments, shown by the dotted line, is a continuation of the Pennine chain – the major watershed of England, at this point dividing the headwaters of the Rivers Severn and Trent. The area chosen corresponds roughly to what most would define as the Black Country, although they contain sizeable rural areas to the west in the modern South Staffordshire district and to the south, in north Worcestershire and do not contain the Smethwick and Handsworth areas. This will not please all readers, but a least offers a geographically consistent area – and indeed on that will be seen proves historically useful to consider. It has the potential to offend almost everybody!

(a) (b)

Figure 1. Definition of the study area: a – river catchments, b – location of modern towns.

The Stone and Bronze Ages

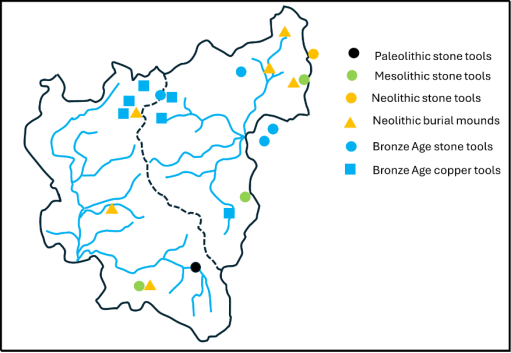

Reference (4) gives an excellent overview of archaeological finds in the area of the Black Country from the Palaeolithic era through to the Roman period. The information presented there is summarised in the map shown in Figure 2 for the Palaeolithic (950,000-9500 BC), Mesolithic (9500-4000 BC), Neolithic (4000-2400 BC) and Bronze Ages (2400-700 BC). (4) gives more detail of the various finds, and only some broad points will be made here. The first and most obvious is that the majority of finds lie just outside the modern urban area to the northeast and the south, or in rural enclaves within it (such as the Sandwell Valley and Barr Beacon). This is almost certainly due to the destruction of archaeological material by industrialisation. Secondly however, there do seem to be a couple of clusters -one in the Aldridge area around Castle Old Fort, and one on the watershed around Wolverhampton. But the huge time period under consideration needs to be borne in mind – these finds were from a wide variety of periods. Nonetheless they do suggest that there was some limited habitation of the area in the prehistoric periods.

Figure 2. Archaeological finds in the Stone and Bronze ages drawn from information in (4).

The Iron Age

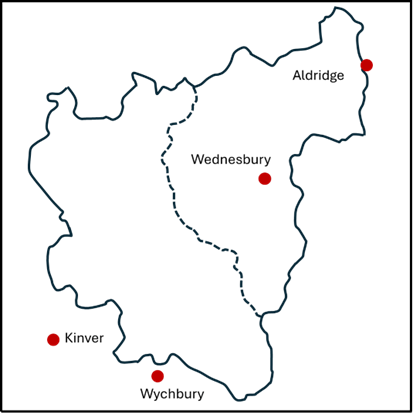

Now let us turn our attention to the situation in the Iron Age before the Roman invasion (700-43 BC). There is in fact very little that can be said with any certainty. However, there are a small number of hill forts in the area – three just outside the study zone at Wychbury in the south (4) Kinver in the southwest (5) and at Castle Old Fort near Aldridge in the northeast (6). There was also probably one at Wednesbury within the study area, although the evidence for this is recent and probably not conclusive (7). These are shown on Figure 3 and three of them seem to line up nicely in a southwest / northeast direction. The spacing along the line suggest that there may also have been one at Dudley on the boundary between the catchments, the traces of which will have been long obliterated by the castle. The configuration suggests a defensive alignment – but who was defending what from who is not in any sense clear. Copper horse bridal fittings have also been found at Wychbury and Castle Old Fort (4).

Figure 3. Iron Age hill forts.

The Roman Period (43 BC – 400AD)

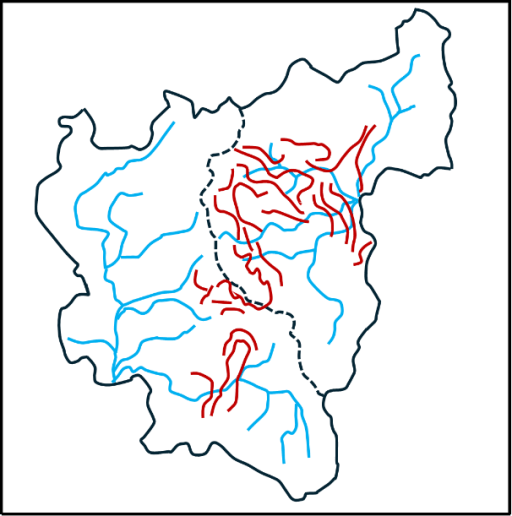

The first truly historical fact about the area that can be relied on is that there were a number of Roman army marching camps in the Greensforge area (8) – see Figure 4. In total there seem to have been two auxiliary forts and five marching camps, which can be dated to the early years of the Roman invasion (45AD to 80AD). They were probably used as the Roman army pushed north and west into England, but also seem to have an intensive period of occupation around the Bouddican revolt of 60AD. These camps were short lived, and there is no evidence of occupation after about 80AD. There is however some evidence of civilian occupation close to the site near Camp Hill, throughout the Roman period (8). An intensive network of roads also remained. These linked into the major arteries of Watling Street to the north and Ryknield Street to the east (figure 4). The importance of Greensforge seems to have been as a ford over the River Smestow. The roads that converge there can be identified with some confidence are as follows (9).

1. A road to the south, to the salt producing areas at Salinae, modern day Droitwich.

2. A road to the north to Pennocrucium, modern day Water Eaton, on Watling Street.

3. A road to the northwest to the major city of Viroconium (Wroxeter), with a branch to Uxacona (Redhill), again on Watling Street.

4. A road to the west to Bravonium near Leominster –presumably with a crossing of the Severn near Quatford, south of Bridgnorth.

Figure 4. Roman Roads in the Black Country

All of these roads can be traced, at least in part, on modern maps and on the ground. Note that the roads from Salinae, through to Viroconium, and onwards to Chester, formed a major “saltway” for the transport of that precious commodity. In addition, the existence of another road can also be indirectly inferred. – from Letocetum (Wall) on Watling Street, south of Lichfield, possibly via Wednesbury before passing through The Straits in Sedgley (another name often linked with Roman Roads) and then heading for Greensforge (10). A further road that probably ran northwest from Metchley in the south to Pennocrucium on Watling Street, can be traced on the ground at its southern and northern ends. Thus, it is likely that there were two roads crossing the Black Country from southwest to northeast and southeast to northwest, that would have crossed in the vicinity of Wednesbury. The precise line of these roads has again been obscured by industrialisation.

Such a road network would form an important focus for both military and civilian business, and as noted above, it is more than likely that there was some sort of small-scale occupation at Greensforge throughout the Roman period. One might expect something similar in the Wednesbury region.

In terms of Roman political structures, the Black Country sat close to the boundaries of three civitas or tribal territories – those of the Cornovii in the upper Severn Basin, the Dobunni in the lower Severn basin, and the Corieltauvi, largely in the Trent basin. Although it is not possible to be sure of the boundaries, the territory of the latter was probably to the east of the main English watershed that passes through Sedgley and Dudley. In addition, it is likely that this ridge was also the boundary of two of the late Roman provinces – that of Britannia Prima to the west and Flavia Caesariensis to the east. (4) reports that a Dobunnic coin has been found at Lutley in the south of the study area.

Many modern historians of that period would see continuity between these civitates and late Iron Age tribal groupings, which would place the Black Country on the boundary between three different tribal groups. Thus, in general terms, the Black Country before and during the Roman period would seem to have been a border zone between different tribal groupings, but nonetheless well traversed by both the invading Roman armies and the traders that would have followed in their wake.

The Anglo-Saxon period (400 -1066 AD)

After the Roman armies left Britain in the early firth century, the traditional view has been that the native Britons were gradually pushed westward into Wales and Cornwall by the military force of invading Anglo-Saxon armies and a number of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were established. Over the last few decades, a great deal of archaeological evidence has emerged to show that it was a lot more complicated than that. There were undoubtedly migrations of Germanic speaking people from Europe, firstly in the service of the native British population and later in conflict with them. But there is also much evidence of continuity of agricultural practices and political systems that are simply not consistent with a wholesale replacement of one people by another (11, 12), Genetic evidence, which needs very careful interpretation, suggests that there is a broad similarity of genetic background of all peoples across England and Wales, although there are some very distinctive local genetic variations that could possibly be linked to specific migrations (13). Similarly, there is evidence that the replacement of the Celtic British language (old Welsh) by a Germanic form (proto-old English) was not a uniform process with some limited evidence emerging that Germanic languages were spoken in England during the Roman period (14), and of the survival of pockets of British speakers across England into the 9th and 10th centuries (11).

So, we have a very complex picture emerging of the movements of peoples and languages across England in the immediate post Roman era. What can be said with a little more certainty is that there were significant movement of people in the second half of the sixth century, when the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms come into view, with evidence of migration from the east to the west (15, 16). In my view this was probably triggered by the climate cris caused by large volcanic explosions in 536 and 543, and by the arrival of the bubonic plague (the Justinian plage) at about the same time (17).

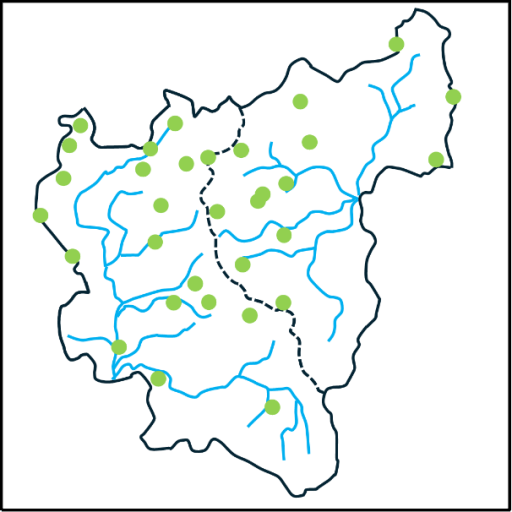

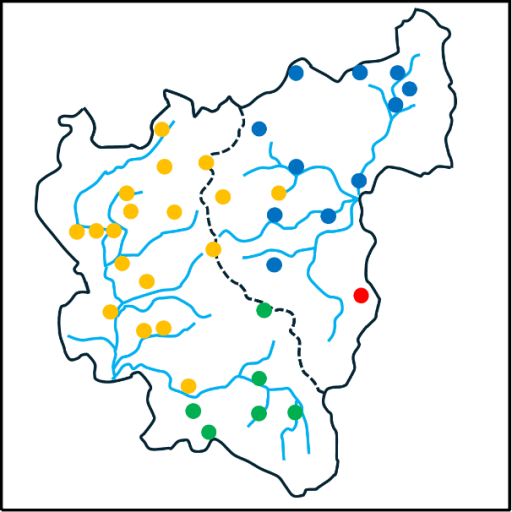

But what does this say about the Black Country in that period? Here we turn firstly to place name evidence. Within our study region most names undoubtedly have an Anglo-Saxon origin. But there are some that are or earlier, British or even older origin. Some of these relate to geographical features – the Rivers Stour, Smestow or Treasle, and the Tame, and the hill names of Barr and Penn (3). Just to the west of the study area there are a number of British names – Kinver, Morfe and possibly Quatt, whilst inside our study area we have Compton (containing the root Welsh cwm for valley) and Walsall, the first component of this being a British name. These names again suggesting that the Black Country in this period was something of an ethnic and linguistic borderland. When we come to the English names, there are two clusters that stand out – those names containing the component “leah”, meaning woodland clearing, and those containing the component “tun” meaning settlement or dwelling. These are shown in figures 5a and 5b. The former strongly suggest that these names originate from a migration of English speakers into a forested area in which they created their own smallholdings and settlement.

(a) (b)

Figure 5. Place name elements: a – leah, b – tun.

Moving on, can anything be said about the political and social groupings in the area? There is strong evidence that two of the Roman Civitas in the area morphed onto territories or kingdoms with Anglo-Saxon names – the Dobunni to the south became the Hwicce and the Cornovii to the west became the Wroecansaete. From the early seventh century most of our study area was part of Mercia, and indeed the Hwicce and the Wreocansaete were absorbed fully into Mercia by the end of that century. The boundary between the Hwicce and Mercia can be traced from the Diocesan boundaries between Worcester and Lichfield, which date back to the late seventh century when they were set up as dioceses to serve the two kingdoms. In our study area, this boundary passes along the Stour, with the Hwicce to the south and Mercia to the north, although the area around Dudley seems always to have been in Worcester diocese. This in turn was matched by the county boundary when the counties were formed in the tenth century. The boundary between Mercia and the Wreoconsate in the early Anglo-Saxon period seems to have been along the Severn to the west of the Black Country – indeed the tenth century county boundaries of Staffordshire extended as far as the Severn. North of our study area, the boundary seems to correspond to the modern county boundary between Staffordshire and Shropshire which follows the watershed between the Trent and the Severn. The incorporation of the area west of the Black Country to the Severn into Mercia would have given them direct access to Bridgnorth – which at that time would have been near the head of the navigable waters of the Severn, and thus accessible by ships from Bristol and beyond, and would offer considerable trading opportunities.

In a charter of 854 relating to the boundary of lands near Cofton Hacket in Worcestershire, preserved in Hemming’s Cartulary, a particular point is described, on the boundaries of the Worcester and Lichfield dioceses, that is a boundary between the Tomsaete, and the Pencersaete (18) and possible with the Arosaete (19). It is generally accepted that the Tomsaete were a Mercian people associated with the River Tame, and indeed this point is at the southern edge of the Tame catchment. Similarly, the Arosaete, who are mentioned in the Tribal Hidage (20), are regarded as the inhabitants of the valley of the River Arrow, in the territory of the Hwicce (19). Again, this point is at the northern end of the Arrow catchment. Cyril Hart has argued that this implies that the Pencersaeten were a people to the north and west of this point, and he suggest they were a Mercian tribe, centred on Penkridge, to the north of Wolverhampton (19). This seems to have become the accepted identification and can be found in a number of texts. Clearly the name suggests that there might be some association with the Penn / Pensnett area, and if the tribe were centred in Penkridge, then this area would certainly be included. However, the author remains unconvinced by this identification. If it were true this would imply that the Pencersaete extended across two catchments – that of the Stour / Smestow which flow into the Severn, and that of the Penk in the upper reaches of the Trent catchment. This seems to the author unlikely, and not consistent with the other tribal boundaries in the area, with the probability being that the bounds of the Pencersaeten extended only over the Stour / Smestow region i.e. just one catchment, and probably centred on the Penn region.

There is another interesting possibility concerning the Hwiccan territory. Green (20) notes that there is a cluster of names with components relating to the Hwicce in Rutalnd in the East Midlands, and speculates that this might be the region from which an Anglo-Saxon tribe called the Hwicce migrated westward in the later sixth century. If this was the case, we could see this tribe as assuming power in the former area of the Dobunni, and the area becoming associated with its name. As I said, the situation concerning migration / kingdom formation etc is very complicated.

At least in the early part of the Anglo-Saxon period, the Roman roads would have remained in use, and probably for many centuries after that. No doubt they were used by those engaged in both commerce and warfare during this period, as they passed by the growing settlements in the area. There were a couple of occasions however when there was more substantial activity. In 893 the Great Heathen army of the invading Vikings marched from near the River Lea north of London to Bridgnorth, where presumably they were met by others coming up the Severn from the Bristol Channel (21). The most obvious way would have been up Watling Street to Wall, then along the proposed road through the Wednesbury area to Greensforge and thence on to Bridgnorth. The passage of the army, with its associated foraging, might have been an uncomfortable experience for those living in the area. Then again in 910, a Viking army moving north out of Bridgnorth was pursued by the combined Mercian and Wessex forces and overtaken and defeated in the Tettenhall area (22). Again, one might expect the route of both armies would have involved the road network passing through Greensforge.

In response to Viking attacks on Mercia. King Alfred’s daughter Aethelfleda and her husband built defended settlements or burghs across Mercia, one of which is reputed to be at Wednesbury (23). However no hard evidence of an early fortification has been found at Wednesbury- but this hasn’t stopped the council from erecting a statue of Aethelfleda at the entrance to Wednesbury bus station – see the header to this blog.

The Conquest and Domesday (1066 – 1086 AD)

When we come to the Domesday survey, we have for the first time detailed information about our study area. Domesday lists 38 manors in our area and these are shown in figure 6 – from the excellent compilation of (24). The colours in this figure indicate the administrative region in which the manors fall – yellow for Seisdon Hundred in Staffordshire, blue for Offlow Hundred, again in Staffordshire, green for Client Hundred in Worcestershire and blue for an entry in Northamptonshire Domesday. It can be seen that the boundary between Seidon and Offlow hundreds basically follow the watershed, although a couple of Seisdon manors (Ettingshall and Bilston) fall into the Tame catchment. The boundary between Client is Worcestershire is along the Stour as would be expected from the Diocesan and County boundaries, with Dudley to the north. The Northamptonshire entry is for (West) Bromwich – which seems to have been included by mistake with its Lord’s entries in that county.

Figure 6. The Domesday manors

The Domesday book also contains much factual information about each manor. However, as all who use this information will know, the details need to be treated with some circumspection. It was compiled from oral evidence by many different people and there are many inconsistencies in the way the data was collected and is presented. This is particularly true of the numerical data for the hidage (originally a measure of area, but by the time of Domesday also a fiscal assessment), the number of ploughlands (the area that could be cultivated by one person) and the number of plough teams. There is however more consistency in the information about Lordship in 1066 and 1086, and the number of workers in various categories (25), and this information is shown in table 1 below. This shows the number of workers in each manor in 1086, in the following categories.

- Free men with on average about 30 acres of land and two plough oxen;

- Villagers of Villeins, unfree and bound to the Lord but with similar holdings to Free Men;

- Smallholders of Bordars, unfree with about 5 acres of land and use of the communal plough team;

- Cottagers, unfree with very meagre land holdings;

- Slaves, owned by the Lord;

- Priests.

The Lords in 1066 and 1086 are also given. The manors are ranked in terms of total number of workers. This order is perhaps surprising to modern eyes. Of the major modern industrial towns in the area, only Wolverhampton is near the top of the list in terms of population. The others – Wednesbury, Dudley, West Bromwich, trail behind, and one, Walsall, is simply not present in the list. The major centres in the area at Domesday were Sedgely, on the watershed between catchments, and Halesowen to the south. Many of the manors had very few workers of any sort. Of those workers the Villagers were the most common, accounting for 56% of the total, which is in line with the larger English picture. 11% of the population were slaves – a perhaps somewhat shocking statistic to modern eyes – with the major concentrations in Halesowen, Wolverhampton and Wombourne. The number of priests is small at 6, and one suspects must be an underestimate. The overall number of workers is 580. Allowing for a household size of 5, which seems a reasonable assumption, gives a total population somewhere around 3000. Even if the Domesday survey omits sections of the population, or if the assumed average household number is too small by a large factor, the population is tiny in comparison to the current population of the Black Country boroughs, which is something over 1 million.

The effect of the Norman conquest on land ownership is starkly clear. In 1066, the major Lords were King Edward with 11 manors, the Canons of St Mary’s Wolverhampton (now St Peter’s) with 5, and Countess Godiva with 3. There were 14 other Lords. By 1086, the number of Lords had been reduced to four. In the main the lands of King Edward had passed to King William; the Canons of Wolverhampton had retained their manors (although one suspects that by then the body of Canons had been thoroughly Normanised) and the Bishops of Chester had retained their single manor. The rest were now under the Lordship of William Fitz Ansculf, who held 98 manors in total across the country, centred on his castle at Dudley. As elsewhere in England, we see how revolutionary and far reaching the Norman takeover was.

| Free | Villagers | Small holders | Slave | Priests | Total | Lord in 1066 | Lord in 1086 | |

| Halesowen | 4(a) | 42 | 23 | 10 | 2 | 77 | Wulfwin | Earl Roger |

| Sedgley | 45 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 51 | Earl Algar | William Fitz Ansculf | |

| Wolverhampton | 6 | 30 | 14 | 50 | W’ton St Mary | W’ton St Mary | ||

| Bloxwich | 16 | 11 | 1 | 28 | King Edward | King William | ||

| Shelfield | 16 | 11 | 1 | 28 | King Edward | King William | ||

| Wednesbury | 16 | 11 | 1 | 28 | King Edward | King William | ||

| Wombourne | 14 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 26 | Thorsten | William Fitz Ansculf | |

| Bushbury | 15 | 2 | 2 | 19 | Countess Godiva | William Fitz Ansculf | ||

| Crockington | 14 | 4 | 1 | 19 | King Edward | King William | ||

| Essington | 15 | 2 | 2 | 19 | Countess Godiva | William Fitz Ansculf | ||

| Kingswinford | 14 | 4 | 1 | 19 | King Edward | King William | ||

| Swinford | 5 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 19 | Wulfwin | William Fitz Ansculf | |

| Pedmore | 3 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 18 | Thorger | William Fitz Ansculf | |

| Cradley | 4 | 11 | 15 | Wigar | William Fitz Ansculf | |||

| Dudley | 1 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 15 | Earl Edwin | William Fitz Ansculf | |

| (West) Bromwich | 10 | 3 | 13 | Brictwin | William Fitz Ansculf | |||

| Ettingshall | 9 | 3 | 12 | Thorsten | William Fitz Ansculf | |||

| Wednesfield | 6 | 6 | 12 | W’ton St Mary | W’ton St Mary | |||

| Bilston | 8 | 3 | 11 | King Edward | William Fitz Ansculf | |||

| Himley | 8 | 3 | 11 | Ravenkel; Wulfstan | William Fitz Ansculf | |||

| Orton | 7 | 2 | 2 | 11 | Wulfstan | William Fitz Ansculf | ||

| Upper Penn | 8 | 2 | 1 | 11 | Earl Algar | William Fitz Ansculf | ||

| Trysull | 4 | 1 | 5 | 10 | Thorgot | William Fitz Ansculf | ||

| Rushall | 6 | 2 | 8 | Vithfari | William Fitz Ansculf | |||

| Willenhall | 5 | 3 | 8 | King Edward | King William | |||

| Amblecote | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | Earl Agar | William Fitz Ansculf | ||

| Compton | 4 | 3 | 7 | King Edward | King William | |||

| Tettenhall | 4 | 3 | 7 | King Edward | King William | |||

| Lower Penn | 1 | 6 | 6 | Countess Godiva | William Fitz Ansculf | |||

| Lutley | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | W’ton St Mary | W’ton St Mary | ||

| Bradley | 4 | 4 | Untan | William Fitz Ansculf | ||||

| Oxley | 4 | 4 | Alric; Godwin. | William Fitz Ansculf | ||||

| Seisdon | 2 | 2 | King Edward | William Fitz Ansculf | ||||

| Bescot | 0 | King Edward | King William | |||||

| Chasepool | 0 | William Fitz Ansculf | ||||||

| Haswic | 0 | W’ton St Mary | W’ton St Mary | |||||

| Pelsall | 0 | W’ton St Mary | W’ton St Mary | |||||

| Tipton (b) | +Chester | +Chester | ||||||

| Totals | 6 | 327 | 182 | 65 | 6 | 580 |

Table 1 Domesday manors from (24). ( a- Specified as Riders , b- Part of the Bishop of Chester / Lichfield manor. Breakdown of workers not given. )

A look beyond Domesday

Before closing, there is perhaps one further point that is worth raising. Ultimately it was the geological wealth of the area that resulted in its transformation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and specifically its coal reserves. But the coal didn’t suddenly appear in that era – it was there all the time and in many places there were surface outcrops. The locations of these are shown from the Coal Authority web site (26). It is very likely that these resources were exploited on a small scale from the Roman period onwards. The major transformation of the area came in the last few hundred years, but the seeds of that transformation were being sown well before Domesday.

Figure 7 Coal outcrops from (26).

References

- Dilworth D (1973) “West Bromwich before the Industrial Revolution”, Black Country Society ISBN 0 9501197 9 2

- DEFRA (2024) “Stour Upper Worcestershire Rivers and Lakes Operational Catchment” https://environment.data.gov.uk/catchment-planning/OperationalCatchment/3502

- DEFRA (2024) “Tame Upper Rivers Operational Catchment” https://environment.data.gov.uk/catchment-planning/OperationalCatchment/3438

- Hodder M (2020) “Long before it was black: the Black Country in Prehistoric and Roman times” The Blackcountryman 54.1

- Historic England (2024) “Kinver camp, a univallate hillfort”, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1015432

- Heritage Gateway (2024) “Castle Old Fort” https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=304477&resourceID=19191

- Birmingham Live (2008) “Remains of Iron Age fort found in Wednesbury” https://www.birminghammail.co.uk/news/local-news/remains-of-iron-age-fort-found-72785

- Cox D (1997) “Greensforge Roman Sites”, Blackcountryman 30.3

- Shropshire History (2024) “Shropshire Roman Roads”, http://shropshirehistory.com/comms/romanroads.htm

- Horovitz, D. (2003) “The place names of Staffordshire”, published by David Horovitz, Berwood, ISBN: 9780955030901

- Oosthuizen S (2017) “The Anglo-Saxon Fenland”, Windgather Press

- Dark K (2002) “Britain & the End of Roman Empire”, History Press ISBN 0752425323

- Leslie S + 18 other authors (2015) “The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population”, Nature 519, 309–314 https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14230

- Nash-Briggs D (2011) “The language of inscriptions on Icenian coinage” in “The Iron Age in Northern East Anglia: New Work in the Land of the Iceni”, Archaeopress, ISBN 978 1 4073 0885 2 https://www.academia.edu/24106378/The_Language_of_Inscriptions_on_Icenian_Coinage

- Green C (2020) “Britons and Anglo-Saxons: Lincolnshire AD 400–650”, Studies in the History of Lincolnshire, History of Lincolnshire Committee ISBN 0902668269

- Jones G (1996) “Penda’s footprint; Place names containing personal names associated with the early Mercian kings”, Nomina 21, 29-62 https://www.snsbi.org.uk/Nomina_articles/Nomina_21_Jones.pdf

- Guardian (2024) “Solar storms, ice cores and nuns’ teeth: the new science of history”, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2024/feb/20/solar-storms-ice-cores-and-nuns-teeth-inside-the-new-science-of-history

- Finburg, H. (1961) “The early charters of the West Midlands”, Leicester University Press, ISBN: 9780718510244

- Hart, C. (1977) “The kingdom of Mercia” in Mercian Studies, edited by Ann Dornier, Leicester University Press, ISBN 10: 0718511484

- Green C (2016) “The Hwicce of Rutland? Some intriguing names from the East Midlands”, https://www.caitlingreen.org/2016/03/the-hwicce-of-rutland.html

- History in the West Midlands (2024) “History of the Vikings in the West Midlands” https://historywestmids.co.uk/pages/history-of-the-vikings-in-the-west-midlands

- Wikipedia (2024) “Battle of Tettenhall” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tettenhall

- A history of Wednesbury (2024) “Beginnings” http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/Wednesbury/Beginnings.htm

- Powell-Smith A (2024) “Open Domesday” https://opendomesday.org/

- Hull Domesday project (2024) https://www.domesdaybook.net/home/hullproject

- Coal Authority (2024) https://mapapps2.bgs.ac.uk/coalauthority/home.html