Three recent blog posts here, here and here, contain transcripts of newspaper reports that describe the restoration of All Saints Church in Oakham in 1858, under the direction of Gilbert Scott. It is clear from these reports that at the time the church was in a very bad state of repair and most of the restoration was concerned with repairing defects, particularly to the roofs, renovating historical features and replacing much of the internal furnishings. However there was one major area of the church where significant work was carried out that went far beyond simple repairs – to the chancel and to the east end in general. In his condition assessment Scott (1) wrote

The chancel has a roof of modern date concealed by a flat plaster ceiling which cuts across the chancel arch. The same roof extends over the north chancel aisle, thus deforming the east end, by placing two divisions under one gable. The north aisle has most beautiful oak panelled ceiling, which happily conceals its roof from within. The south aisle of the chancel has modern roof, of the very meanest description, so that in the interior of the chancel and its aisles we have first a plain flat plaster ceiling to the chancel itself; then to the north aisle a beautiful oak ceiling, showing the manner in which the ancient builders treated their work; and on the south aisle the roof of modern hedge-carpenter, such as would disgrace a cart-shed.

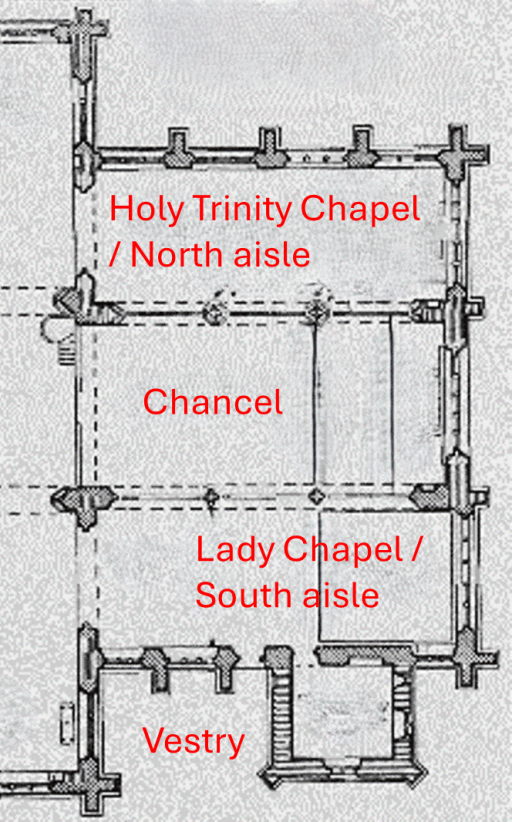

It is not altogether clear what is being described here, particularly in the first sentence, and this is the aspect of the work that will be considered in this post. First of all, let us consider the current (2024) state of that area of the church. A plan is given in figure 1 and shows the chancel, with the 13th century Holy Trinity chapel to the north and the Lady Chapel (built around 1480) to the south (the chapels are the north and south aisles referred to in the above quotation) (2). Figure 2a,b,c,d shows views of chancel and the chapels from the west end of the church. The chancel arch, referred to by Scott can be seen in figure 2d. It can be seen that the chancel itself is higher than the chapels to either side and certainly higher than the chancel arch, so the ceiling that Scott took exception to has been removed.

Figure 1. Plan of the east end of the church

Figure 2. a – North aisle / Holy Trinity chapel; b -Chancel; c – South aisle / Lady chapel; d – view from nave showing chancel arch.

Photographs of the east end of the church from the outside are shown in figure 3. There is no natural viewing point to take an overall photograph and the view is obstructed by trees in the churchyard, but, despite the odd perspective, both chapels and the chancel can be seen. The change in stonework around and above the chancel window shows the rebuilding of the 1850s.

Figure 3. The east end of the church

Happily we can gain an understanding of what this end of the church looked like before the restoration from an 1851 model kept in the church (3). This is in a glass display case, currently in the north transept, and was not altogether easy to photograph, largely because this entailed standing on a pew, turning through ninety degrees and trying to photograph something in a glass case next to a window, with multiple reflections. Nonetheless, a rather poor quality photograph is shown in figure 4. The caption on the display case reads

In loving memory of Mary Grinter who passed to her rest on 10th February 1950. Age 87 years. This model was made by her father John Pitt Coulam (1833-1898)

Figure 4. The 1851 model

Figure 5. Photograph of the east end of the church showing the roof line of the 1851 model.

The east end in this photograph can be seen to be very different from the photographs of figure 3. Figure 5 shows the 1851 roof line from figure 4 superimposed on the photograph of figure 3b. And from this one can understand what Scott meant. The chancel seems to have been reduced from its original height (which the height of the chance arch suggest was similar to today), and a pitched roof added over both the north aisle / Holy Trinity, chapel and the chancel itself. Thus, the two chapels indeed share a gable, and the roof / ceiling of the chancel would cut across the chancel arch in a very un-elegant fashion. The window at the east end would also seem to have been deliberately lowered to fit into the new arrangement. Figure 6 shows, in an edited version of figure 2b, how Scott would have seen the interior of the church, with the top of the chancel arch blocked, a lower flat ceiling in place, and a smaller east window

Figure 6. The chancel as would have been seen by Scott, with chancel arch blocked, lowered flat ceiling and smaller east window

Scott’s work changed all this, restoring the chancel to its original height and adding sound roofs and spectacular internal ceilings. A new east window was inserted, which, the 2003 church guide (3) tells us, was criticised at the time for being of “decorated” rather than “perpendicular” form. Funny what folk get upset about.

So why on earth did this happen – why was the original rather elegant design of the chancel and chapel changed in this way, presumably sometime in the 15th to 17th centuries. I can think of two possible reasons. The first is wholly utilitarian – the chancel, and in particular the roof, may have been in a very poor state of repair, and required extensive renovation and repair. The arrangement criticised by Scott could have been a cheap way of making that end of the church reasonably sound, if rather ugly. The second reason has a more theological basis. After the Reformation, the Elizabethan settlement enforced conformity of practice – in particular taking down the altars at the eats ends of chancels and replacing them, for the purpose of celebrating holy communion, with a table placed lengthways in the chancel, around which communicants would have gathered, with the celebrant on the north (long) side of the table. The combined chancel and north chapel would thus have provided a typical Elizabethan “communion room”. A surviving example of such an arrangement can be seen locally at Brooke. (figure 7) where the spacious chancel is separated from a north chapel by a simple screen. This arrangement was only temporary and after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, with the Laudians in the ascendency, the altars at the east ends of chancels were reinstated with little opposition. Some clergy however continued to celebrate from the north end even with the altar in the new positions, and indeed, this is still the case in a few places.

Figure 7. Interior of Brooke church showing chancel from adjacent north chapel (from Wikipedia File:St Peter’s Church, Brooke, Rutland 13539728115.jpg – Wikimedia Commons)

Whatever the reason, I have to admit (albeit grudgingly) that Scott was correct in this case in his desire to restore the chancel to its gothic glory from what seems to have been a somewhat botched Elizabethan / Stuart arrangement.

One further point arises. In the north aisle / Holy Trinity chapel there is a large chest tomb, with no dedication, placed lengthways next to the chancel (figure 8). It is said in (2) to be early 16th century – perhaps around the time of the Reformation. The images of sheep bells or wool weights on the side have led to the suggestion that it might be the tomb of a wool merchant. In the chancel arrangement before Scott’s restoration this would have been very prominent – indeed in the centre of the gable, possibly between two altar positions. One can speculate that the tomb was either placed in this position deliberately or indeed whoever was responsible might also have rebuilt the chancel / chapel to give the tomb such a prominence.

Figure 7. Chest tomb in Holy Trinity chapel.

- Re-opening of Oakham Church. Stamford Mercury 12th November 1858

- ‘Parishes: Oakham’, in A History of the County of Rutland: Volume 2, ed. William Page (London, 1935), British History Online [accessed 21 October 2024].

- Aston N (2003) All Saints Oakham, Rutland. A guide and history.