Preamble

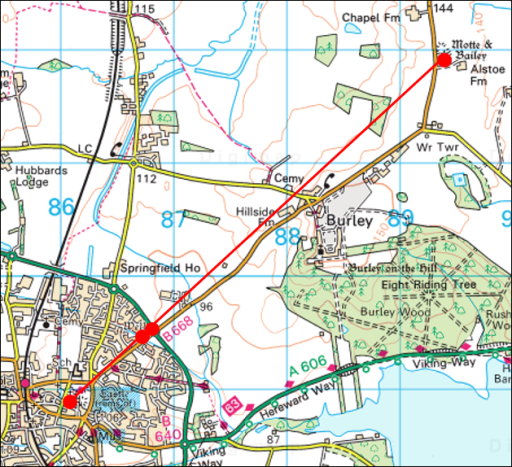

In a post “A possible Anglo-Saxon church group at Oakham in Rutland” from May 2024, I noted that All Saints Church in Oakham, and Our Lady’s Well to the north east were on what could be a mid-summer sunrise / mid-winter sunset solar alignment. I went no further than simply noting this, and didn’t speculate further about what it might imply. One always needs to be cautious about such alignments – they can be simple coincidences, and, if they are being looked for, can be found in the most unlikely places. For example from Borrowcop Hill in Lichfield, possibly an ancient burial mound, there was until recently a perfect alignment with the medieval spires of Lichfield Cathedral and the cooling towers of Rugeley power station, the latter sadly now demolished, which can hardly be of ancient origin. That being said, a reader of the May 2024 post sent me some further information that suggests that a cluster of Stone Age / Bronze Age / Iron Age remains have been found to the north east of Our Lady’s well that could also be on the same alignment. Looking at this further, I realised that several kilometres to the north east of that, and again on much the same alignment, we have Alstoe Mount, another historic monument. These are all shown on the Ordnance Survey map extract of Figure 1 below. The nature of this possible alignment, along the axis of the mid-summer sunrise and mid-winter sunset is discussed further in this post.

Figure 1. The possible alignment. The sites are shown as red circles – from the south west to the north east these are All Saints church in Oakham, Our Lady’s Well, the historic monuments and Alstoe Mount.

The sites

All Saints church, Oakham

All Saints Church is Oakham (Figure 2) is a twelfth century church with thirteenth to fifteenth century additions. Internally it is pure Victorian, having been restored by Gilbert Scott. However it almost certainly stands on the site of an Anglo-Saxon church, and a church in Oakham is mentioned in the Domesday book. A compendium of historical information is given on the church website.

Figure 2. All Saints Oakham and Oakham Castle (photograph by the author)

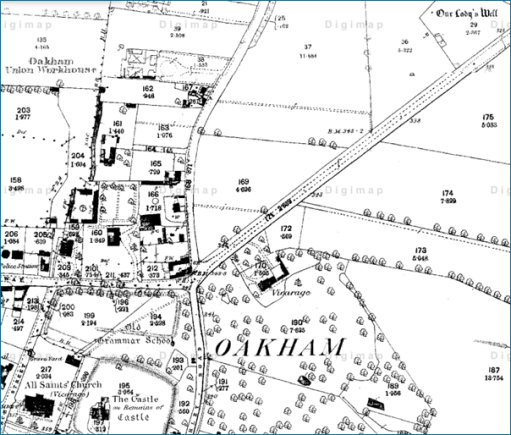

Our Lady’s Well

Our Lady’s Well is a historically well-attested pilgrim site to the north east of All Saints church – see Figure 3. To quote from Leicestershire and Rutland’s Holy Wells by Bob Trubshaw from 2004;

Our Lady’s Well was once famed for curing sore eyes – providing that a pin was thrown in first. In 1291 indulgences could be obtained by visiting Oakham Church during its patronal festival and, for a price, joining a pilgrimage to Our Lady’s Well. In 1881 it was visited by the future Queen Alexandra. The well is to the north-east of the town, in a somewhat overgrown area between the Cottesmore road and a modern housing estate (NGR SK:866095).

It’s current condition is no better, and it is now impossible to access the well, in an overgrown plot of wasteland, which seems a shame.

Figure 3. Location of Our Lady’s Well from the 1880 Ordnance survey Map (All Saints church is at the bottom left, and the well at the top right.)

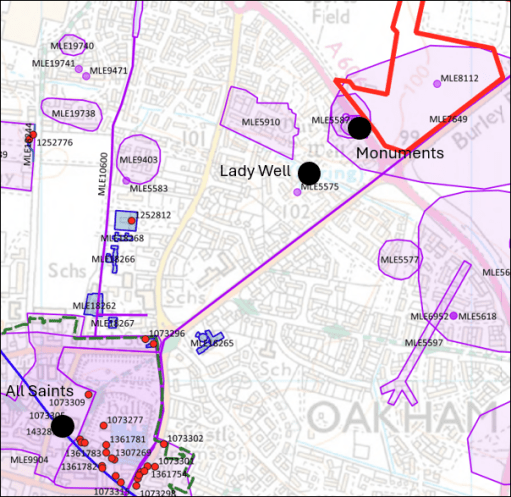

The Stone Age / Bronze Age / Iron Age monuments

The material I was sent concerning the Stone Age / Bronze Age / Iron Age monuments came from “Land off Burley Road Oakham, Vision and Delivery Document” produced by Pigeon Investment Management with regard to a proposed hosing development. Figure 4 is taken from that document and shows the location of Our Lady’s Well and the relevant monuments.

Figure 4. The Stone Age / Bronze Age / Iron Age monuments (from Land off Burley Road Oakham, Vision and Delivery Document)

The monuments are listed as follows, where the numbers are those on the Historic England National Heritage list.

MLE5587 – Possible Mesolithic site west of Burley Road

MLE5592 – Late Iron Age/Roman site west of Burley Road

MLE5593 – Bronze Age burial, west of Burley Road

MLE5594 – Neolithic pit circle site west of Burley Road

Alstoe Mount

The substantial mound of Alstoe Mount (Figure 5) is described on the Ordnance Survey map as a Motte and Bailey. That is almost certainly not true. It was probably the Moot location for Alstoe Hundred. Details of the mound and the surrounding deserted village are given in the Historic England list entry.

Figure 5. Alstoe Mount (photograph from Historic England by Alan Murray-Rust, 2016)

The possible solar alignment

A current mid-summer sunrise / midwinter sunset direction from Oakham is 47.5 degrees east of north (from SunCalc). However obtaining a precise value to compare with the possible alignment shown in Figure 1 is difficult for two reasons. Firstly the actual direction of sunrise and sunset has varied over the millennia – and as things stand, we have no date for which a calculation can be made. This change is however small – of the order of 0.2 to 0.5 degrees. Also the apparent direction from any point depends upon the precise topography of the horizon over which the sunrise / sunset is observed – and as we know nothing about the observation point or the direction of observation, this is again not possible to specify. This again results in an uncertainty of around 0.5 degrees. So all we can probably say is that we are looking for an alignment of 47.5 +/-1.0 degrees east of north.

The actual directions between All Saints Oakham and the other sites is as follows.

Oakham to Our Lady’s Well – 46.3 degrees

Oakham to Stone Age / Bronze Age / Iron Age monuments – 47.1 degrees

Oakham to Alstoe Mount – 47.8 degrees

Again there is uncertainty here – particularly in the specification of the precise site at Our Lady’s Well of any structure that might have been visible from All Saints, and similarly the precise position of any relevant structure in the monument field. The location point for All Saints (taken as the centre of the building) could be around 10m to the east or west. This can have an effect of the bearings of Our Lady’s Well and the monuments by around 0.25 degrees. Considering these uncertainties the above bearings and a sunrise / sunset direction of 47.5 degrees seem broadly consistent, and thus there does seem to be some evidence for all four sites lying along a solar alignment of some significance.

But there is another issue – that of elevation. A cross section along the proposed alignment is shown in Figure 6. From this it is clear that Alstoe Mount would not be visible from Our Lady’s Well or from the Monument field, and would only just be visible from All Saints if any observation platforms that existed there and at Alstoe were raised off the ground by a metre or so. Beacons however would have been visible.

Figure 6. Section through the proposed alignment (from Google Earth Pro.).

Discussion

So what does the above analysis lead to. Firstly I think there is plausible (but far from conclusive) evidence for a mid-summer sunrise / mid-winter sunset alignment, at least between the Monument field / Our Lady’s Well and All Saints, and possibly between Alstoe Mount and All Saints. but the available evidence gives us no chronological information as to when the alignment might have been of significance. Our Lady’s Well is first mentioned in the late Middle Ages and All Saints and Alstoe Mount can only be said to become of important in the pre-conquest period. There is no evidence at all, except in the monument field, for the other sites being important in the Stone Age / Bronze Age / Iron Age. So in my view it is probably better to stop at this point – acknowledging that there may be a solar alignment, but not taking speculation any further. The boring, cautious approach I guess, but I don’t think there is much more to be said.