Introduction

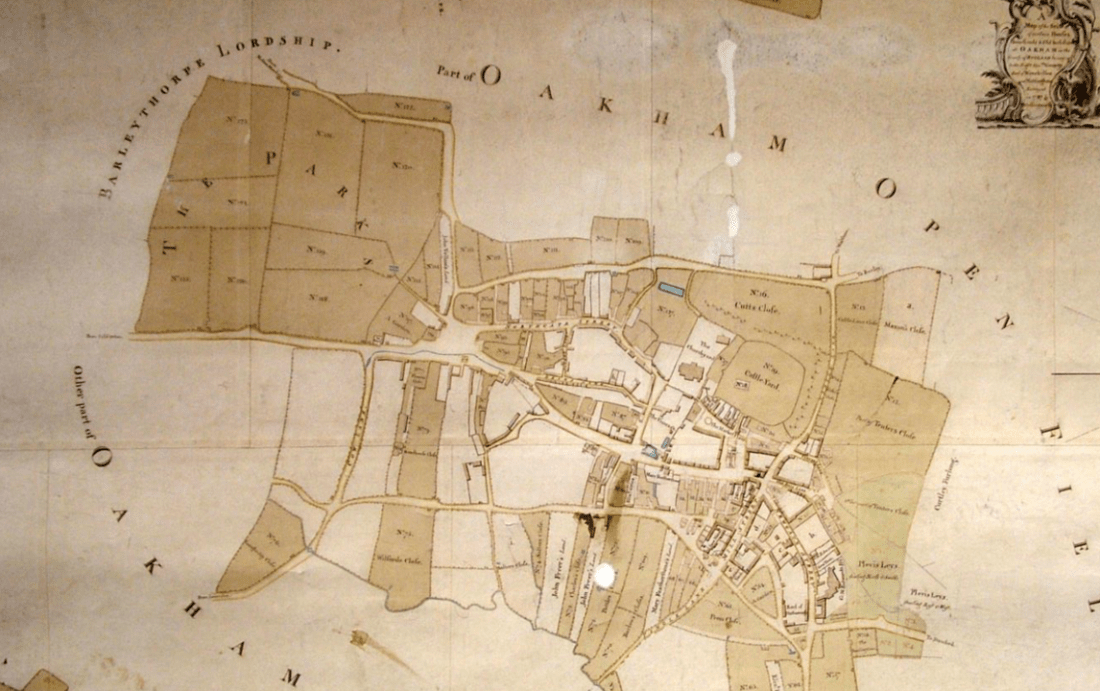

In the monograph “Oakham Lordshold in 1787”, Clough (2016) considers the map of the town of Oakham in Rutland produced for Lord Winchilsea in that year. This is the earliest map to show significant detail of the urban topography of the town, and from it Clough was able to infer some aspects of its late Anglo-Saxon / early Norman topography, in particular the existence of two enclosures encompassing the castle and the church, and the castle and a large portion of the town. In this post. I take his considerations somewhat further and, by considering the likely Anglo-Saxon road network around Oakham, infer some further features of the Anglo-Saxon urban topography.

Oakham connections

Cox (1994) in his extensive survey of Rutland place names, identifies a number of settlements in the Oakham area that were likely to have been in existence in the sixth and seventh centuries i.e. early on the Anglo Saxon era. These are as follows.

- Place names ending in -ham, meaning village or estate. These include Oakham itself; Langham and Wymondham to the north west; Greetham and Grantham to the north east, Empingham to the east and Uppingham to the south.

- Place names ending in -dun meaning a large hill, of which the only one in the vicinity of Oakham is Hambleton.

- Place names associated with the Anglian tribe of the Hwicce of which Whissendine to the north of Oakham is the only one locally.

- The villages of Brooke, which has an early attestation, and Braunston, which incorporates an early form of Anglo-Saxon name and has possible Roman antecedents.

- The -well names meaning spring, and in particular Ashwell, although this might be slightly later than the others.

- The major settlements in the wider region either with proven continuity since the Roman period or are of an early form- Leicester, Nottingham, Lincoln and Stamford.

In what follows we presume that in the Anglo-Saxon and Norman periods, Oakham had road / pathway connections to these early settlements that are, broadly, the predecessors of those we see today at least out of the settlements themselves. Country roads are very conservative topographical features and change little over the centuries. Within, and on the entry to settlements, they would however have been more prone to change, because of building and commercial developments. In these terms we will consider seven such roads that converge on Oakham and in particular we attempt to trace the “natural” course of these roads into and through the town, again assuming that these are the courses that would have been followed in the Anglo-Saxon period, rather than the courses that have developed over the centuries.

But first a broader point is worth making. Oakham was in the ninth and tenth centuries was in many ways at the centre of the Danelaw, with roads passing through it that connected Leicester in the west to Stamford and Lincoln in the east, and Northampton in the south with Derby and Nottingham in the north. As such, it is likely to have been of some strategic importance, particularly during the period when King Edward and Lady Aethelflead finally defeated the Danish armies in the area between 910 and 920.

The Anglo-Saxon roads

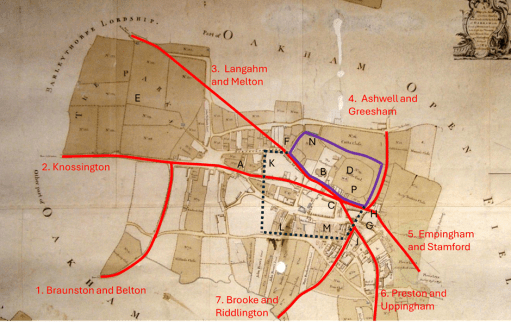

The roads that we are considering are shown in Figure 1 on a copy of the 1787 map as given in Clough (2016). These are as follows.

Figure 1. The proposed early road layout

- Road 1 from Belton and Braunston (and beyond that Leicester) that runs up what is now Braunston Road and West Road (formerly known as Cow Lane) and joins Road 2 to the west of Oakham.

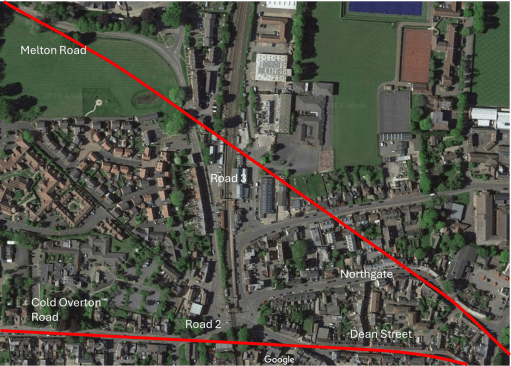

- Road 2, the current Cold Overton Rd from Knossington, runs in a west to east direction, across what would become many centuries later the railway crossing and into Oakham. If the line of the road is continued, it runs along Dean Street (A) towards the church (B), and not along High Street. This straight alignment is very clear from the satellite view of figure 2. I will argue below that High Street was a relatively late development and was laid out in the Norman period. I have then shown the road running to a point in the current market place (C) in front of the castle (D) although this last stretch is conjectural.

- Road 3 is the road from Melton Mowbray (and Derby and Nottingham beyond) through Wymondham and Langham. The modern approach to Oakham is via a sharp 90 degree turn along the railway down towards the level crossing. It will be seen below that this route was actually in place in the 16th century at the latest, so it is not a modern development. However, here we take the natural line of the road to continue from the north of the area marked as the Parks (E) towards the sharp kink in the modern Northgate (F) and then following Northgate and Church Alley to a junction with Road 2 in the Market Place. Again, this natural course is very obvious on the satellite view of Figure 2. This seems a much more natural route into the centre of the town.

- Road 4 is from Ashwell and Greesham (and beyond that Grantham) that is taken to follow the existing course of Burley Rd. east of the castle to a junction with Road 5.

- The course of Road 5 from Stamford and Empingham has changed significantly over the centuries, as it was moved to loop around Catmose Hall. Clough conjectures that it used to entire town through either or both of Bull Lane (G) or Tanners Lane (H) to the north of Bull St. We choose the latter course here as it allows this road to meet those from the west in the Market Place.

- Road 6 from Uppingham and Preston follows its modern course to the end of Mill St. (J) and then cuts across to meet the other roads in the Market Place,

- Road 7 from Brooke and Riddlington follows the current course of Mill St. to a junction with Road 6 (J).

Figure 2. Satellite views of the western and northern approaches

The Saxon / early Norman enclosures.

Figure 1 also shows two enclosures. The black dotted lines is a (very) conjectural boundary of the Anglo-Saxon settlement, based on the discovery of boundary ditches at K, L and M summarised by Clough. The purple solid line is the enclosure surrounding the castle and the church identified by Clough, largely on the basis of the flooded ditch at N (that has also been identified in archaeological investigations). Taken together these two enclosures would seem to represent the extent of the Anglo—Saxon and early Norman settlement. The strategic and defensive position of the castle (and in particular the Motte in the south east corner P) adjacent to the meeting point of the roads through the town is very clear. The most striking point about the proposed reconstruction is the absence of the High Street – its anomalous orientation with regard to the other roads suggests it postdated the original road layout. South Street was however likely to be in existence early as it marks the southern boundary of the enclosure. Note its original course ran straight from the west to the east, and did not diverge to the south east at its eastern end.

Changes in the Norman period

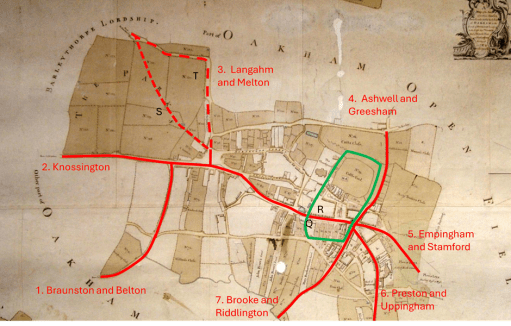

Figure 3. The post-conquest road layout

Figure 3 shows the road system and enclosures in the later Norman period. Clough identified the enclosure outlined in green that contains the castle and the portion of the town to the south. He speculates that the pattern of enclosures was changed when the manor was relinquished by (probably) William II and divided between Lordshold and Deanshold (the Dean referring to being that of Westminster Abbey), with the results that the church and the castle holdings were separated. This enclosure was again identified on the basis of a flooded ditch at Q. Clearly the function of this enclosure is very different and seems to be about controlling the movement of people and goods through the town (presumably for taxation purposes). It is like that this is the period when the current High Street came into existence. The Speed map of 1611 (Figure 4) shows “Bargate” at R, (built into the current Flores House) where presumably people and goods were assessed . The road system has also been changed to ensure all traffic flows along High Street. In the west, Road 3 was rerouted, probably in the first instance to follow the current line of Park Lane (S) down to Road 2. At some point the area named as the Parks was enclosed (both routes are shown on the 1611 map), and the route would again have been changed to run around this area, resulting in the modern road configuration (T). The current traffic chaos around the level crossing on the Cold Overton Road thus has its genesis many centuries ago! The combined roads 2 and 3 were then rerouted along the new High Street, rather than down Dean Street. To the east, it is likely that the Stamford Road was rerouted to come into town via what is now Bull Lane.

Figure 4. The Speed map of 1611

Loose ends

In this final section we note a number of what might be called loose ends in the above argument – the lack of destinations for one of the identified roads; the lack of direct roads from a significant place in the locality and the nature of the town “gates”.

A road to nowhere

Road 2 approaches Oakham on a straight route from the west, and within the town becomes Dean Street. But where was it coming from? There are no settlements out in that direction that can be confidently given an early date. Two thoughts come to mind – either that it was part of a somewhat roundabout route to Leicester, or that it was the route to what can be surmised to be early fortifications of the Rutland border to the west (where a number of names indicate beacons). There are no doubt other possibilities.

The route to Hambleton

There are clear indications in Domesday that the major settlement in the area at the time was Hambleton, and it was suggested above that this settlement was of an early date. As far as can be ascertained from the fairly recent maps that are available, the route there was a 90 degree junction of the Stamford Road (see the 1900 Ordnance Survey map of Figure 5). However the map shows a pedestrian way to the west of the junction that cuts of a corner and is a much more natural way to Hambleton. It seems possible that the Stamford Road bifurcated at that point with branches to Empingham and Stamford to the north and Hambleton and Ketton to the south, but that this junction was supressed during the enclosures. So Road 5 might better be referred to as the road to Hambleton, Empingham and Stamford

Figure 5. The road to Hambleton (from 1900 Ordnance Survey map

The gates

“Gates” is an ambiguous word. It can either refer to a physical gate to the town, or be a derivation from the Norse -gata simply meaning road. Bearing this in mind, Clough identifies two gates – an East gate at the entry of the Stamford Road into the enclosure around the present Bull Lane, and a West gate – the Bar-gate mentioned above. The road system was clearly arranged to direct all traffic through these, and resulted in quite a small central enclosure.

Now, whilst no south gate has ever been identified, from the earliest maps, there is a Gibbet Gate shown on the Speed Map on Stamford Road (Figure 4). This is someway outside the enclosed areas, and is this case the word gate probably simply defines a road rather than anything else. albeit one leading to a somewhat grisly destination.

The name Northgate, however, appears on a number of maps. On the Speed map this is positioned somewhere near the railway crossing, and on later maps, the current Northgate is known by either that name or by Northgate Street. Again, this could either refer to an actual gate to the town, or simply a way to denote a road. But if there was an actual North Gate, where was it? In my view, the most likely position is at the current sharp junction of the modern Northgate – F in figure 1, on the original Melton Road and at the possible confluence of the Saxon town and Castle / Church enclosures. A modern photograph is shown in Figure 6 below – taken from the east showing the possible location of the north gate (the thatched cottages) and the line of the road from there to the castle.

Figure 6. The possible location of the north gate

References

Clough T. H. McK. (2016) ” Oakham Lordshold in 1787 – A map and survey of Lord Winchilsea’s Oakham estate” Rutland Local History & Record Society, Occasional Publication No 12

Cox B (1994) “The place-names of Rutland” English Place Name Society