Introduction

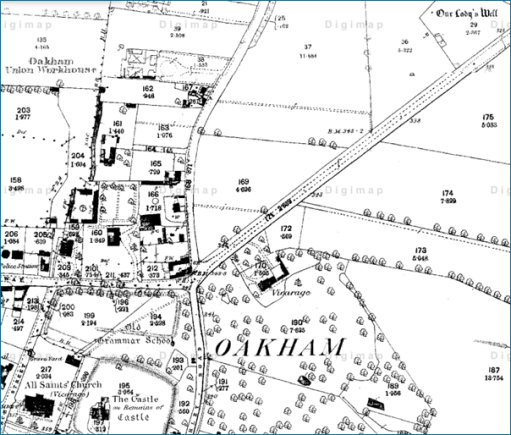

In this series of three related posts, I present transcripts of the press reports concerning the re-opening of All Saints church in Oakham in November 1858. This is done primarily to make the source documents for that event available and easily readable, and there is no discussion of their contents. That will come later. The material is all found in the British Newspaper Archive and the archive OCR text forms the basis of the transcripts, although. As with any OCR text, this has needed considerable editing, which, as I am sure the reader will find, has been imperfectly done. The material presented in the three parts is as follows.

- Part 1 contains the notice of the re-opening the from the Leicester Journal of 5th November 1858 and a report on the event itself from the Stamford Mercury of 12th November 1858. The latter contains the text of the report by Gilbert Scott that describes the state of the church before the restoration and what, in his view, needed to be done.

- Part 2 contains a report of the opening from the Leicester Journal of 12th November 1858. This covers some of the same ground as the Stamford Mercury report, and whilst not including Scott’s report, does give details of the opening event, including the sermon that was preached.

- Part 3 (this part) is from the Lincolnshire Chronicle of August 24th 1860, and gives the text of a lecture that was given at Oakham Castle entitled “Gothic Architecture” by the Rev Canon James, one of the principal proponents of the Gothic in the region, where the changes that were made to the church are explained and justified.

Leicester Journal 5th November 1858

ALL SAINTS’ CHURCH, OAKHAM.

THE RESTORATION of this Church, in which great and general interest has been shown, is now so near completion that the of November may fixed for the RE-OPENING. It is purposed, therefore (D.V.), to have Divine Service, on WEDNESDAY, November 10th, Eleven o’clock am., Morning Prayer, with Sermon by

THE REV. E. MEYRICK GOULBURN, D.C.L,

Chaplain in ordinary to Her Majesty, and Minister Quebec Chapel, London;

Three o’clock, p.m., Evening Prayer, with Sermon by

THE REY. CANON JAMES, M.A.

Rural Dean, Vicar of Theddingworth and Sibbertoft.

On THURSDAY, November 11th, Seven o’clock p.m., Evening Prayer, with a Sermon by

THE BEV. J. R. WOODFORD, M.A.

Vicar of Kempsford, Gloucestershire.

On SUNDAY, November 14th, Eleven o’clock, in, Morning Prayer and Holy Communion, with a Sermon by

THE HON. and REV. CANON STUART, M.A.

Rector of Cottesmore.

6.30. p.m., Evening Prayer, with Sermon by

THE REV. THOMAS YARD, M.A.

Rural Dean and Rector of Ashwell.

A Collection will be made each service in aid the Restoration Fund. A deficit of about £300. remains this; to meet which the sum raised these Collections the only resource available.

The presence and aid of all who take interest this important work is respectfully invited.

In order to secure accommodation for those who reside out of the town, admission until 10.50 a.m. on Wednesday morning will be by cards only; at 10,50 the doors will be thrown open.

Those who propose to attend, are requested to apply for as many Cards as they desire, to one of the Churchwardens ; or to any resident member of the Restoration Committee; or to the Secretary, the Rev. C. A Stevens.

Heneage Finch, Vicar

Rich. Davies, Churchwardens. William Ratcllff, Churchwardens

The Agricultural Hall will, by the kind permission of its managers, be thrown open to Visitors during Wednesday, the 10th November. Arrangements have been made for the supply of Refreshments there on the arrival of the Morning trains, and during the day.

Stamford Mercury 12th November 1858

For a considerable period the very filthy and dilapidated condition of the magnificent church of All Saints, at Oakham, was a subject for regret, not only to those who worshipped within its damp and dingy-looking walls, but to all admirers of Christian architecture. At length the noble sum of £800. was given through the Architectural Society of the Archdeaconry, by unknown donors, which originated the fund that has procured the restoration of the edifice, and which was re-opened for divine worship on Wednesday last. When there seemed to be no longer doubt respecting the raising sufficient amount for beautifying the church the services of Mr. G. G. Scott, the eminent architect, were sought, and after inspecting the fabric returned to London and drew up the following report, which he forwarded to the Rev. Heneage Finch, the Vicar.

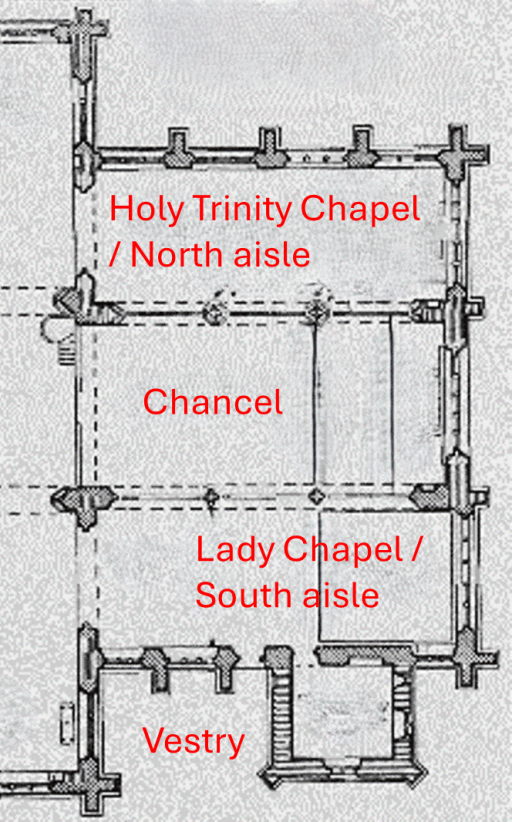

I have made a careful survey of your parish church, with a view to forming an opinion as to the extent of the reparations and restorations which are requisite to putting it into a satisfactory condition, and as to the probable cost of the work. The church is, as you are aware a remarkably fine one. It is the work of several different periods, extending from the end of the 12th to the commencement of the 16th century. I have not been able to trace out the course of alteration and addition which has brought to its present form but may mention that its earliest feature is the inner doorway of the porch which is of the end of the 12th century. The next date are the interior of the porch itself and the lower parts of the south wall, with blank recess or window in the east side of the south transept, which are of the first half of the 13th century. Then come the corresponding parts on the north side, with the single pillars in both transepts. The chancel arch, and some minor portions, which are the beginning of the 14th: and the tower, with perhaps the pillars and arches, of the same, and some other portions, which are of the latter part of the same century; while the chancel and the clerestory, and probably the north chancel aisle, are of the 15th, and the south chancel aisle of the 16th centuries. Various, however, as are the dates of these different portions the church, they unite to forming a symmetrical and harmonious whole, having generally the aspect of a church of the 15th century.

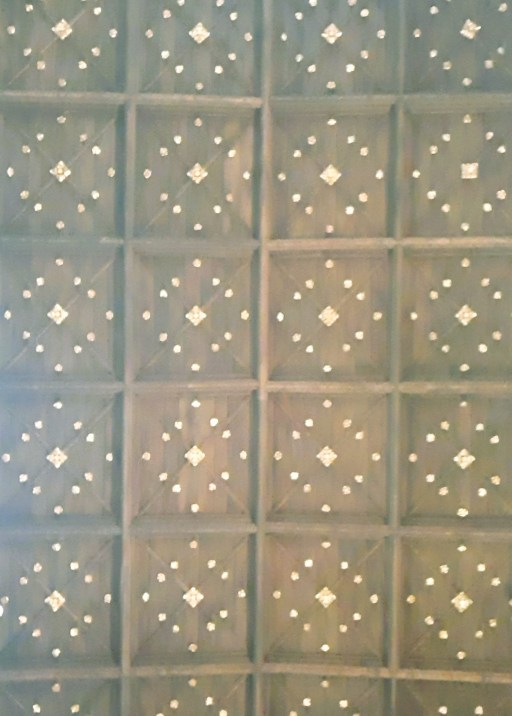

In describing the present condition of the church, I will commence with the roofs. The roof of the nave (which pretty good roof in design, though constructed as to press somewhat severely upon the clerestory walls) is a very sad state of decay : one half of it was repaired some years ago, and means were taken to reduce the pressure upon the walls, It will be necessary to do the same throughout; but at the same time the roof will require thorough reparation. I fear that it will be found that a very large proportion of the timbers are decayed. These must be replaced with new oak, the boarding and lead renewed, and the whole restored to a perfect condition. The roofs of the nave aisles are ancient, and better condition than that of the nave itself, but require considerable repairs, and the lead and boarding must be re-laid. The roofs of the transepts have been repaired some thirty years since, and much of the timbers concealed by plastering. I would recommend the substitution of oak panelling for this, and such general repairs as may be found necessary. The chancel has a roof of modern date concealed by a flat plaster ceiling which cuts across the chancel arch. The same roof extends over the north chancel aisle, thus deforming the east end, by placing two divisions under one gable. The north aisle has most beautiful oak panelled ceiling, which happily conceals its roof from within. The south aisle of the chancel has modern roof, of the very meanest description, so that in the interior of the chancel and its aisles we have first a plain flat plaster ceiling to the chancel itself; then to the north aisle a beautiful oak ceiling, showing the manner in which the ancient builders treated their work; and on the south aisle the roof of modern hedge-carpenter, such as would disgrace a cart-shed.

The mode of treatment I would recommend would as follows. First, as the chancel roof has been originally of high pitch, would renew it in that form, and in a manner suited to the beauty of the church. Secondly, I would thoroughly restore the ceiling the north aisle, bringing the external roof to its original level Thirdly, I would put over the south aisle a ceiling corresponding in some degree with that on the north aisle. The roof of the porch and vestry would also require reparation. The walls of the church seem generally pretty substantial, but have suffered much from mutilation, and require careful reparation throughout. The cusps of the windows have nearly everywhere been cut out. The east window has been renewed on a most extraordinary design. Many of the mullions are shattered, and must be renewed, Generally, all mutilated and decayed parts must be renewed, the internal stonework cleaned, the plastering of the walls repaired or renewed as the case may be, the clerestory walls, which have been thrust out must be strengthened, the parapets reset where necessary, the pinnacles restored, and the whole rendered perfect and substantial The tower has either through settlement, or through the effects of lightening been somewhat split down its south-eastern angle, and has some few other defects. – These must be substantially repaired, and I would recommend the insertion of a tier of strong iron ties to prevent their re-appearance. The floor of the tower immediately over the church must be renewed, and the other floor and the bell timbers substantially repaired. Of the internal fittings I have but little to say. They exceed in meanness even what is usual in country churches. And there must be but one opinion about them – they must entirely cleared away, and the whole refitted in proper manner with good oak seats. There are numerous remnants of old screen work of very character, and some remains ancient seats. These will be useful guides in designing the new fittings The floors must almost entirely new. The doors must be new, excepting that to the south porch, which is ancient and ornamental, but requires restoration. The glazing should be renewed throughout, and stained glass introduced from time-to-time opportunity may offer. While these reparations are in hand, it would be very desirable that the church should be efficiently warmed.

I estimate the probable cost of the works as follows. Those connected with the church and tower with £2300; those to the chancel fabric £575 and fittings £225, (£800); those to the south aisle of the chancel, fittings £320, fittings £80 (£400); those to the north aisle of the chancel fabric £275, fittings £7L (£350): making in all about £3850. The above calculation is made on the supposition of everything being done the best manner, the roofs and the whole executed in a manner worthy of so fine a church, and need I hardly say that the church so restored would be a most noble and beautiful structure.

The above report was dated April 21,1857, and on the 30th of the same month the Vicar convened a meeting of the inhabitants and others interested the restoration and re-seating the church. Geo. Finch Esq. presided. Mr. Scott’s report having been read, the following resolution was passed “That this meeting having heard the report of Mr. Scott on the state of the parish church, and acknowledging the liberal offer of donations to the amount of 800L towards carrying it into effect, is of the opinion that thus opportunity should be taken advantage of and make an immediate and strenuous effort to restore the church to condition befitting its high purposes. A committee wan immediately formed. Mr. Scott was employed as architect and subscriptions to the restoration fund solicited., the Rev. C. A. Stevens accepting the arduous office of honorary secretary.

The call has been liberally responded to as the following subscriptions will show.

Geo. Finch Esq. £1000

Anonymous, £400

The Dean and Chapter of Westminster, £300

The Rev. Heneage Finch, the Vicar, £200

The late Wm Ades , Esq., £150

The Church Building Society, £150

The Marquis of Exeter, Lord Aveland, the honourable Colonel Lowther, Miss Jones, Miss B. Jones Mrs. Doria, Mrs. Bicknell, the Rev. Brown (Lyndon), the Church Building Society of the Archdeaconry of Northampton, and the Governors of Oakham Grammar-school and Hospital, £100 each

The Hon. G. H. Heathcote, the Rev. J. Jones (Burley), the Hon G. J.NoeL S. Parke, Esq. (Spalding), the Hon. and Rev. A. G. Stewart (Cottesmore), the Rev Thos. Yard (Ashwell), Mr. Adam, and Mrs. Hicks (Jermyn-terrace), £50 each

Messrs. Crowson and Sons, £40

Mrs-Fydell Morcott, £35L

Messrs. Eaton, Cayley, and Co., (Stamford) £30Major-General FludyeZr (Ayston), Col. Freer (Leamington), Miss Thompson (Ketton), Colonel and Mrs. Talbot Clifton, Mr. Hough, Mr. F. King, Mr. Mackinder, Mr. Clarke Morris, Messrs. Morris and Co., Mr. Samson, and the Rev. W. S. Wood, £25 each

The Rev. c. S. Elbcott (Whitwll), Chiselden Henson, Esq. (Cheltenham), Wm. Hopkinson, Esq. (Stamford), Mr. and Miss Hunt and friends (Clapton), F.J.Mould, Esq. (Brompton) the Hon. and Rev. Noel (Exton), the Misses Wingfield (South Luffenham), Mr. Dain, Mr. Churchwarden Davies, Mr. Hawley, Miss Mason, and Mr. Wellington, £20 each

H. W. Baker, Esq. (Cottesmore), and Ayscough Smith, Esq. (Leesthorpe Hall), £10 10s each

Miss Belgrave (Preston), the Rev. F. G. Burnabv (Barkestone), General Johnson (Wytham on the Hill), John Keal, Esq. (London), Thos. Lawrence, Esq. (Preston), the Rev D. Royce (Netherswell), Colonel and Mrs. R. W. Wood, Mr. Brown (Melton-road), the Rev. T. Byers, Miss Jane Layng, Mr. Morton (Egleton), Miss Mould, Mrs Rawlings, Mr. R. Simpson, the Rev. C. A. Stevens, Mr. Tirrell (Egleton), and Mr. S. C. Turner, £10 each

The Rev. Thos. Field (Cambridge), the Rev. G. H. Parker (London), Mr. Brown (Ashwell-road), Mr. Burn, Mr. Churchwarden Ratcliff and Mr. Thos. Shuttlewood, £5 5s each

The Rev. H. Applebee (Whissendine), the Rev. Canon Argles (Barnack), the Rev. C. Atlay (Barrowden), the Rev. Jas. Atlay (Cambridge). the Rev. the Master Catherine Hall, Edw. Conder Esq (London), the Hon. and Rev. K Cust (Belton), the Yen. Archdeacon Davys (Peterborough), Mrs. Decker (Lyndon), the Rev T. Dove Dove (Frome Solwood), the Rev. C. J. Ellicott (Cambridge), Mrs. Hayton (Kimbolton), the Rev. Canon James (Peterborough), the Rev. H. Jones (Greetham), the Rev. J. Pullein (Kirkthorpe), Wm. Sheild, Esq. (Uppingham), Mr. E. Wright (Melton), N. W. Wyer, Esq. (Bedford), anonymous, Mr. W. Burnett, Mr. Bell, .Mr. Bruce, Miss Butt Mr. D. Cooke, Mr. E. Cunnington (Barleythorpe), Mr. Furley, Mr. W. KeaL jun., Miss Emma Keal, Mr. S. and Mr. J. Tirrell (Egleton), and Mrs. Whyers, £5 each.

Of the £800 which formed the ground-work of the undertaking, £440 now appears in the subscription list as an anonymous donation, and £100 to each the names of the four daughters of the late J. E. Jones, Esq., of Oakham. The Earl of Gainsborough gave £125 to the fund: the north chantry belongs to his Lordship, and in consideration of the above donation the expense of its adornment will be paid out of the general fund.

For the execution the works several firms were solicited send in tenders, and that of Messrs. Ruddle and Thompson, of Peterborough was accepted, the amount of contract being £4400. In a few days afterwords the unsightly furniture was removed from the church, and the restoration proceeded with. In carrying out the undertaking Mr. Scott has strictly preserved every mediaeval detail; even the triangular lines over the tower arch which show gable form of the roof of the earlier church have not been allowed to be erased. He considers that such details show to some extent the history of the church. A portion of the capital the north pillar of the chancel arch was cut away to admit of the erection of the roodscreen, perhaps in the 15th century: the capital illustrated a subject from scripture, but there is not sufficient of the sculpture left enable Mr. Scott effect a faithful restoration he has left the capital in its mutilated form, believing that course be preferable to inserting that which would not be a simile of that chiselled the 14th century. Amongst the improvements effected are— the chancel is floored with Mutton’s encaustic tiles of a rich design, given by the Rev. Lord A. Compton; the aisles are paved with red and black tiles, in pattern ; the interesting Norman font has been removed and re-fixed; the parapet of the nave clerestory has been taken down and re-fixed; the chancel gable and that of the north aisle the chancel have been taken down and re-built; the debased east window has been replaced by a new one of five lights, having deeply sunk and moulded tracery and arches, with columns of polished Derbyshire marble and moulded caps and bases; the pillars, bases, caps, arches, and seats the south porch arcade have been restored; all the windows, cuspings, defective mullions, tracery, jambs, arches, etc. have been carefully restored; the windows have been reglazed with diamond quarries of cathedral glass; all the carvings have been scraped; the whole of the internal stone-dressings of the doorways and windows, pillars, and arches, including tower arches, corbels, stringcourses, quoins, and other dressings have had all the mortar, whitewash etc. taken off; the two galleries over the tower arch have been taken away, and the arch re-opened; and all the piscinas, lockers, tabernacles, etc. restored. The new seats are plain, low, and open: they are three feet high, the poppy-heads being richly carved, the design being similar to several seat ends found in the church before the restoration, and probably the first introduced here after the Reformation. On the seat ends are carvings from natural foliage, including the vine, oak, holly, ivy, maple, hop, thorn, convolvulus, filbert, fig, etc. The fronts of the seats are filled with tracery, having carved spandrils, Ac. The stalls in the chancel have moulded standards, with richly carved finials and arm rests of varied design, and moulded fronts and book rests. The octagonal pulpit is made of the finest wainscot, having traceried panels, the design being in perfect unison with the fittings. The screen (height 3 feet 4 inches) dividing the nave and chancel is formed of a series of trefoiled headed arches deeply moulded and sunk, the cornice being moulded and tilled with bosses. The two screens at the easternmost end, under archways dividing aisles from chancel, have rich tracery heads, supported by circular shafts and moulded caps and bases. The cornice is moulded and embattled, and enriched with carved bosses, the lower part being solid moulded framing. The altar rail and table are of wainscot, and in keeping with the other fittings. The roofs have been thoroughly restored in English oak. The chancel roof is entirely new, the ceiling of which is panelled, and takes the form of the pointed arch, having moulded ribs and carved bosses at the intersections, the part of the roof over the altar being filled with extremely rich wrought tracery. The whole of the roofs are oak boarded and leaded. The gas fittings have been supplied by Mr. Skidmore, of Coventry: the standards are of blue and gold, four of them being erected in the chancel. The warming apparatus has been erected by firm at Birmingham.

Mr. Dent. of the Strand, the maker of the great Parliamentary and other clocks, has been employed to make a clock for the tower of this church, the cost of which, with its erection, will be about £190. It will chime three of the quarters, but not the hour. The time will be ascertained from dials erected under the belfry windows, on the west and south sides of the tower. The design of the- hon dials is quite new: they are perforated throughout and might, with a little extra outlay, be adapted for illumination. The belfry contains six bells: two them have been recast by Mr. Mears of London. About the middle the 17th century peals of were re-introduced into churches to a very great extent. The most celebrated founder this part of the kingdom was Tobie Norris, of Stamford, and plate of bell metal in St George’s church, in that town, thus records the interment of his remains there “Here lieth the body of Tobie Norris, bell-founder.” On one of the bells in the tower of Oakham church is this inscription “Tobie Norris cast me, 1677. God Save the King, T. Meekings.” And on a larger bell, “Tobie Norris, 1677. G. Burton, A. Burton.” Another bell has this inscription ” Henry Perm made me, 1723. Francis Cleeve, W. M. Maidwell, churchwardens.” Many towers this district contain bells cast by Tobie and Thomas Norns, at Stamford, but the site of their foundry is not now known.

The subscribers to the restoration fund have the satisfaction of knowing that the committee secured the services of gentlemen eminent their calling to carry out the important work now on the eve of being completed. Mr. G. G. Scott, the architect, is one of the leading men the profession, his services being sought in most parts of the kingdom on the most important and extensive ecclesiastical edifices. The contractors, Messrs. Ruddle and Thompson, of Peterborough’, have carried out with satisfaction great undertakings at various cathedral and parish churches: they are now executing the extensive restoration at Higham Ferrers church, and only few days ago the contract entered into by them for the roofing and internal fittings at St. George’s church, Doncaster, for the sum of £10,259*., was completed. Messrs. Minton and Co., who supplied the flooring tiles, Mr. Mears, bell founder, who re cast two of the bells, Mr. Skidmore, of Coventry, who supplied the gas standards, and Mr. Dent, the manufacturer of the new clock, are firms known throughout the kingdom.

Wednesday last will be a “red letter day” in the history of the county town of Rutland. As early as six o clock the church bells reminded the inhabitants of Oakham that the anxiously looked for day had arrived when they were again to possess the privilege of worshipping their Maker in their own parish church. The Agricultural Hall was thrown open for the reception of distant visitors on their arrival, where a supply refreshments and good fires had been provided by direction of the committee. By 10 o’clock the workmen had ceased their labours; the committee of management were seen to be busily engaged; and the police were attendance to prevent the pressure of the crowd at the entrances. At half past ten the visitors began to assemble and were conducted to the seats by the committee. The clergy, in their gowns entered in procession. At ten minutes before eleven the doors were thrown open, when those who had not procured tickets were admitted, and the church was quickly filled.

At eleven the service commenced by the Rev. H. Wingfield reading the service for the day: the Psalms having been chanted, the Rev. R. King read the first and the Rev W P Wood the second lesson; the Litany was read the Rev. R. Sorsbia, the communion service by the Rev H Finch the Epistle for the day by the Rev. J.R Woodford, the Gospel by the Rev. C. Stuart, and the Creed by the Rev T Yard The sermon was preached by the Rev. E. M. Goulburn D.C.L., of London. The text was taken from Exodus iii 5. The sermon was eloquent and appropriate; and the choir (from Leicester) efficient and powerful. The church was well warmed and the arrangements excellent. The inconvenience experienced by the strong sun light through the cathedral glass during the morning service will, it is hoped, at no distant day lead to the introduction of stained glass, which is much wanted to subdue the light.

Amongst the congregation were Lord Wensleydale, the Hon. Calthrop, the Hon. Colonel and Miss Lowther, H. Lowther, Esq., MP. Geo. Finch, Esq., Lady Louisa Finch, the Misses Finch, John and Lady Trollope, Colonel R. and Mrs. Wood, the Hon Hy. and Mrs Noel. Miss Noel and friends, J. M. Wingfield Esq. the Misses Wingfield, H. Wingfield, Esq., the Hon. Evans Freke, Captain Doria, General Fludyer. Miss Fludyer, Mrs. Jackson, W. A. Pochin Esq and friends, Mrs. and Miss Baker, J. F. Mould, Esq. the Misses Arnold (Tinwell), W. Sheild, Esq., E. Cayley, Esq, R. de Capel Brooke Esq., Mr and Mrs. Barnard, Mr. and Mrs. Latham, Mrs. Whitchurch and friends, Mr. and Mrs. Harrison; the Rev. Hon. Leland Noel and family, Hon. A. Stewart and family, H. Fludyer, F. E. Gretton, W .J. Williams, C. Nevinson, Lovick Cooper, N. Twopeny, E. Cayley, H. Jones, S. Rolleston, W. Belgrave, H. Yard, C E. Prichard S. Walters P.J. E. Miles, T. Hoskins, M. Garrett, W. Metcalfe, J Noyes, W Ostler, F P Johnson, E. Brown, T. James J. R Woodford, W. S. Wood, T. Byers, R. King, R. Sorsbie J. W. Sherrington, G. E Gillett, G. A. Poole, W. Jay, H. J. Bigg c. A. Stevens, Prescott, T. Peake, T. Cooke, J. Beresford.

ln the afternoon the sermon was preached by the Rev. Canon James, Vicar of Theddingworth and Sibbertoft, from 11th chapter of Luke and 25th verse. The collections in the morning amounted to £174i 0s 6d and in the afternoon to to £31 7s. 1½d, total £205 7s 7½d.

The early hour at which the first train leaves Peterborough’ in the morning prevented many from attending the re-opening of the above church.