Preamble

The Glynne Baronetcy dates back to 1661, with its main estate at Hawarden in Flintshire. The 8th Baronet, Sir Stephen Glynne (1780 to 1815) married Mary Griffin, daughter of Lord Braybrooke. After his early death, he was succeeded by his son Sir Stephen Richard Glynne, the 9th Baronet (1807-1874). I first came across him as the owner of the Oak Farm Iron Works in the Black Country, which was the subject of a spectacular financial crash. Glyne was saved from financial ruin by the efforts of his brother-in-law, the future Prime Minister William Gladstone, at very considerable expense to the latter.

More widely, Stephen Glynne is best known as a church antiquarian. Over the course of his adult lifetime he visited over 5000 churches in England and Wales, making notes, and in some cases sketches of their architecture, plans and furnishings. These notes can be found in 106 volumes now housed in the Gladstone Library at Hawarden. A small minority of these have been transcribed and published, but unfortunately this does not include the volumes containing the Rutland churches. This blog post goes some way towards remedying this, by presenting a transcription of the entry for All Saints Oakham. It is intended as the first fruits of a project to do the same for all the churches in the Oakham Team Ministry that were visited by Glynne. However, this may simply result in the creation of paving slabs for the road to hell.

Stephen Glynne’s description of All Saints Oakham

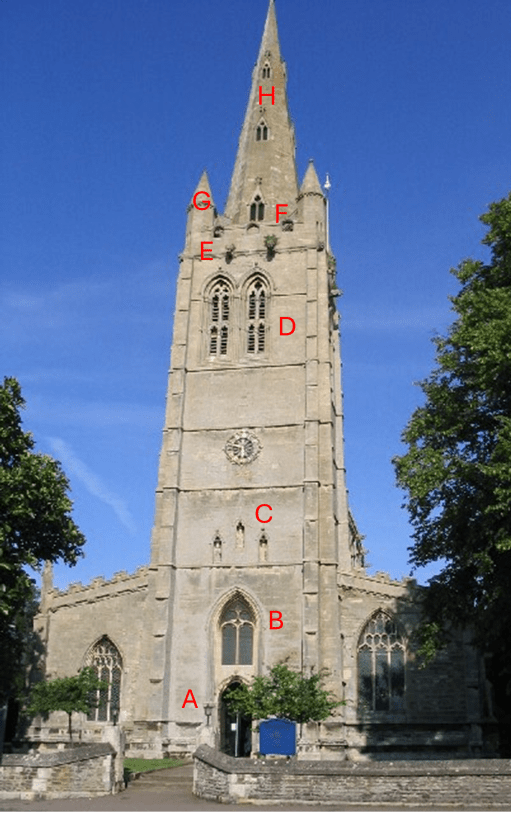

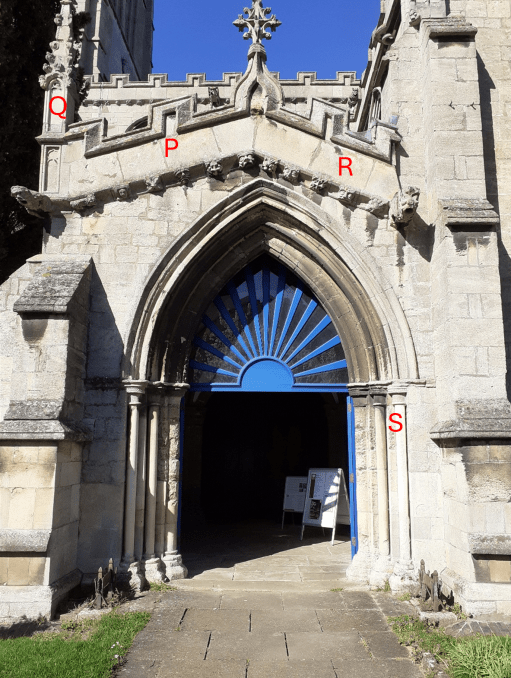

The text of Glynne’s entry for All Saints Oakham is given below, from Volume 33 of his Church Notes, one of three covering Leicestershire and Rutland. It is not dated, but other entries in the same volume indicate the year 1849, and it is likely this applies to the Oakham entry too. Certainly it was written before the restoration of 1858 – see earlier blogs here, here, here and here that deal with that. As written, it was all in one long paragraph, with somewhat dubious punctuation – almost a stream of consciousness approach. I have divided it up into sections with my own headings, and added consistent punctuation, which hopefully makes it a little easier to understand. The letters in brackets refer to the captions on the photographs, which illustrate the text. Numbers in brackets refer to the explanatory notes given at the end of the transcript.

The transcript

General

This is a very large and fine church with large portions of Curvilinear work (1) and some of the later style. It consists of a large and lofty Nave with wide aisles, Clerestory, North and South Transepts, each with one aisle, and a chancel with side aisles.

The tower and the spire

The tower and spire

The steeple is at the west end of the nave. Included within the aisles, it is a remarkably fine composition consisting of a tower with pinnacles at the angles, surmounted by a beautiful spire connecting to the pinnacles by flying buttresses, the work of the Curvilinear period. On the west side of the tower is the door (A) and over it a two light windows included within one pointed arch (B). In the next stage are three small trefoiled niches on the west side (C) (2). The belfry storey has, on each side, two long windows each of two lights divided by a transom and having deep architrave moulding and shafts (D). Just above the nave a rich band filled with heads and foliage (E) (3). The parapet of the tower is pierced at rectangular intervals with small ogee openings (F). At each angle is a small octagonal turret covered by a large pinnacle from there being flying buttresses to the spire (G) (4), which is well proportioned and has several lights of small canopied windows (H).

The body of the church

The whole of the body of the Chancel is embattled (I), there being beneath the parapet at some positions a cornice of heads etc (J) (5). The apex of the gable of Chancel, Transepts and Clerestory is in each crowned with an ogee canopy (K) (6). That of the Clerestory has a fine ornamental cross (L). The Transept ends are enriched with large crocketed pinnacles (M). The northern one is plainer externally than the corresponding one and has much blank wall. The windows of the Nave, Clerestory and Transepts are all Rectilinear (N) (1) but the walls are earlier. Some of the buttresses on the south have crocketed triangular canopies (O).

Transept, Nave and Clerestory

The South Porch

The South Porch has an embattled gable (P) with pinnacles (Q) and cornices of heads (R) (7). The doorway is large and has deep mouldings and shafts of early English character having the nail head in the capital (S). Within the porch are niches on each side.

South Porch

Nave and aisles

The tower opens to the Nave and each aisle has a pointed arch springing from chamfered shafts (S), but much concealed by clumsy boarded partitions and lumber (8). Some of the windows are of three, others of four lights. The Nave and aisles are of considerable width and the divisions are formed by a double row of lofty pointed arches, four on each side (T). The pillars consists of four clustered shafts in lozenge form with the capitals sculptured with heads (U) (9).

The nave and ailses looking towards west end

Transepts

The Transepts are each divided into two aisles by two pointed arches with octagonal pillars (V). The ends of the transept have each two windows under one gable. In the South Transept is the niche with a contracted arch and shafts of early English character, with the piscina (W). On the east side of the same Transept, between the arch opening to the South Aisle and chancel is a window in an arch in the wall of early English work with toothed ornaments in the mouldings (X) (10). In the north transept is a Rectilinear corniced niche in the east wall (Y) and beneath it a trefoiled niche with drain of Curvilinear work (Z).

The South (left) and North (right) transepts

Chancel and chapels

The Chancel with its Aisles has a great portion of Rectilinear work (11). The three east windows are large fine ones of four or five lights but only one retains its tracery. The side windows are of three lights. There are three pointed arches on each side of the Chancel (AA). Those in the south are rectilinear, the piers having fine mouldings carried down the ?? with shafts attached. On the sides on the north the piers resemble those of the nave but have the Tudor flower in the capitals (AB). The north aisle (12) has had a good panelled wood ceiling but now somewhat mutilated. On the north side (13) of the chancel is a rectilinear vestry which has no battlement but the gable is finished by a rich canopied niche and cross. The windows east of the chancel and south arch are under one gable and between their heads is a quatrefoiled circle. There is a niche and stoop near the South door of the chancel externally.

The chancel

The font

The font is Norman of circular form with intersecting arches and shafts (14). The base is square but with corners chamfered off, and moulded with small trefoil arches. There are traces of some fine ??.

Closing remarks

Altogether the interior is not so well kept as it deserves to be. The pews and galleries are shabby and the whole dirty and untidy but the exterior is in good preservation and the stone of excellent quality (15).

Notes

1. The architectural periods referred to in the transcript are Early English (1190 to 1250); Curvilinear (or Decorated (1250 to 1350) and Rectilinear or Perpendicular (1330 to 1530).

2. No mention is made of the statues now in these niches, so it is most likely these were added during the 1858 restoration.

3. This band is above the belfry rather than the nave, so Glynne probably made a mistake here. It is possible however that the carvings were moved during the restoration, but the order of the text suggest that the first explanation is most likely.

4. These might be better described a low flying buttresses – it is difficult to observe them from ground level.

5. The heads cannot be seen on the large scale photograph. However there are some wonderful close up pictures of them on the Great English Churches website.

6. Shown here on the South Transept gable.

7. Again, detailed pictures can be found on the Great English Churches website.

8. This is very much inline with the description given by Gilbert Scott in his survey before the 1858 restoration. However his language was somewhat more robust. The aisles referred to are behind the west wall of the nave in the photo.

9. The capitals are perhaps the most significant heritage aspect of All Saints. I have discussed them at length here.

10. The wording is unclear here, but probably refers to the blind window which now houses the ten commandments.

11. The Chancel and side chapels were the most altered part of the church in the 1858 restoration, and much of what is described by Glynne no longer exists.

12. The current Holy Trinity Chapel. The southern aisle (the current Lady Chapel) is not mentioned.

13. This is a mistake – the vestry is on the south side.

14. The order of text here suggest the font was in the chancel area. However, it now stands close to the west door. Whether that has always been the case, or whether it was moved during the restoration to a more ecclesiastically acceptable position is not clear. I am inclined to think it was moved, as it would have been very awkwardly placed under the gallery if it were at the west end before the restoration.

15. Again, this finds and echo in the condition report of Gilbert Scott before the restoration.