Updated to include new information 17/11/2023

Background

In the aftermath of the dreadful events at the Crooked House (or Glynne Arms) in August 2023 (the timeline of which I have documented here) my interests in the Oak Farm area were rekindled., and I wrote a blog post on the early history of the Glynne Arms that has been quite widely read. Perhaps the main insight to emerge from that post was to restate the often-missed fact that the Crooked House began life as a corn mill on the Oak Farm Estate owned by Stephen Glynne and evolved into a public house in parallel with the rapid industrialization of the estate in the 1840s and 1850s. This point was also made in a blog on the Black country Society site by Steve Roughton, who indeed argued that it was the existence of soft ground around the mill race that caused the building to tilt. The Oak Farm Mill stood on the Himley Brook on the boundary between Kingswinford and Himley parishes, and was powered by water from the brook, stored in a mill pool to the east and released into a mill race before rejoining the brook some way to the west. It was not the only mill in the area. To the east (i.e. upstream) the Himley Brook was joined by the Straits Brook, that formed the boundary between Himley and Sedgley parishes. Just upstream of the confluence, the waters of the Straits Brook were stored in a large mill pond that operated the Coppice Mill, owned by the Dudley Estate. This mill pond extended north to beyond Askew Bridge on the road from Himley to Dudley and is named in some sources as Furnace Pool – allegedly the site of one of Dud Dudley’s experimental furnaces in the 1620s – and the water was used to power the furnace bellows.

In this blog post, we look specifically at the watercourses that supplied the two mills, and how it evolved through the decades. It will be seen that it leads to some speculations that, in the 1840s the original Oak Farm Mill was much modified, and perhaps moved, taking water from the upstream Coppice Mill pool rather than its own. It also suggest that the Crooked House as we knew it up to August 2023 dates from that period.

Mills and watwerwheels

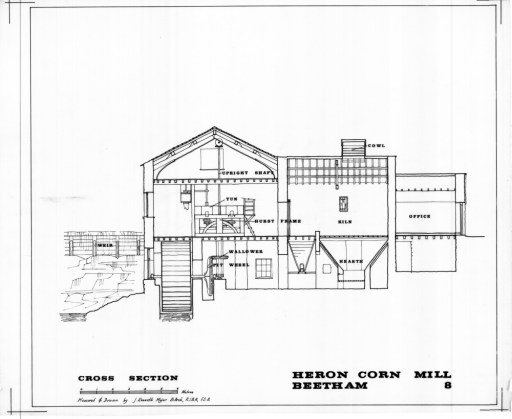

Firstly, however, we need to consider the nature of the mill itself, and in particular the possible waterwheels that were installed. Wikipedia gives a useful article on this. Basically, there are two types of wheel (although with many variants) – overshot and undershot (see Figure 1). Both of these require a differential height (or head) of water – from a reservoir of mill pool upstream, to a mill race downstream. For overshot wheels, the water fills buckets on the wheel circumference and the potential energy in the water is transferred into rotational energy in the wheel. For undershot weirs, the fall of the water upstream of the wheel decreases its potential energy and increases its kinetic energy (and thus its velocity), some of which is transferred to rotational energy in the wheel when it impinges on the vanes. A simple analysis indicates that the power output of both types of wheel is proportional to this height difference raised to the power of 1.5. Of course, the greater the head, the larger the wheel would need to be to extract the power, and the greater the mechanical challenge. The power from the wheel would have been suitably transmitted through gears to grindstones to produce flour from the cereal grains (see Figure 2 for an example from Cumbria). The miller of course would like to have a long period of operation of the wheel, but as water is released to the wheel, the level of the upstream mill pool will fall and the head available and hence wheel power will also fall. At some point the water level will fall below the level of the outlet weir or pipe in the reservoir. Thus, there is an advantage in having a large reservoir from which large quantities of water can be abstracted without too great a fall in the water level. There is no indication which type of wheel was present at the Glynne Arms.

Figure 1. Types of water wheel

Figure 2. Heron Corn Mill, Cumbria

The Oak Farm Mill up to 1840

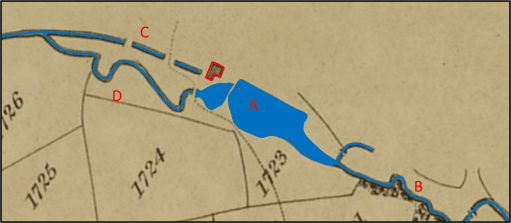

Moving on now to consider the development of the Mill and its watercourses, we will use a number of maps from a variety of sources. Each of the maps represents the same geographical area, and the buildings of the Mill / Glynne Arms are outlined in red, and the watercourses highlighted in blue. In their original forms, some of the maps did not have north at the top in the normal way, so these have been rotated, but the orientation can only be regarded as approximate. Figure 3 is an extract from the 1822 Fowler map of Kingswinford parish. The Oak Farm Mill was just outside the parish, so its appearance on the map is perhaps fortuitous. It is depicted as a simple L shaped building. The mill pool (A) is fed by the Himley Brook to the east (B) and itself feeds both the mill race (C) and the downstream channel of the brook (D). C and D join again at a point downstream. Water would have been diverted along the mill race by a system of sluices when the mill was in operation. The line of the mill race passes under the southern end of the building, which indicates that the mill wheel is at the southern end of the building. The parish boundary is defined by the brook and passes through the centre of the mill pool. The Oak Farm estate was wholly agricultural at this time. As this is a map of Kingswinford parish, nothing is shown of the area to the north of the mill in Himley parish.

Figure 3. The 1822 Fowler Map

Figure 4, from the Kingswinford Tithe map, surveyed in 1839, shows a very similar situation. The Oak Farm Mill is however indicated by a simple rectangular structure over the line of the mill race.

Figure 4. The Kingswinford Tithe Map of 1839

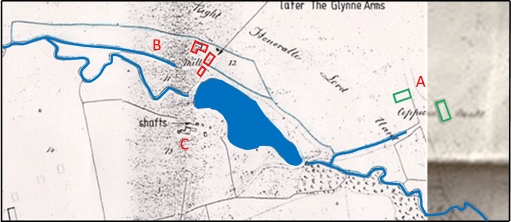

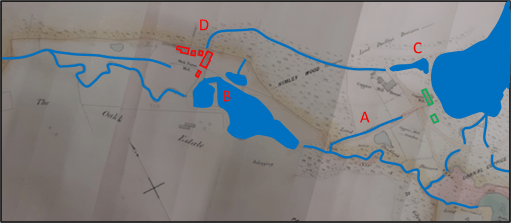

The map of Figure 5 is an extract from a document that was clearly drawn for the owners of the Oak Farm Estate and is dated November 1840. This map was used by Steve Roughton in his blog mentioned above, and I am grateful for his permission to use it here. He originally obtained it from the Clwyd archives many years ago, presumably amongst the Glynne papers relating to their home in North Wales. I have to admit that this is not a place I would have considered looking for details of the Crooked House. This shows a similar situation, with rather more detail of the watercourses to the east (i.e. upstream) and to the north (in Himley parish). In particular the buildings of Coppice Mill (A) are shown in green, with a channel leading from their vicinity into the Himley brook at the top of the Oak Farm Mill pool. The Coppice Mill pool was to the east of the mill buildings and is not shown The Oak Farm Mill itself is now represented by three distinct buildings, which suggests that the simple rectangular form in Figure 4 might be a schematic rather than realistic representation. On the other hand it suggest that the two northern buildings might have been constructed around that period. The line of the mill race (B) passes to the south of the most southerly building suggesting that the waterwheel was on the south of that building. Mine shafts of Oak Farm Colliery can be seen to the south of the brook near the downstream end of the Oak Farm Mill pool (C).

Figure 5. The Oak Farm Estate map from November 1840

The Oak Farm Mill from 1841

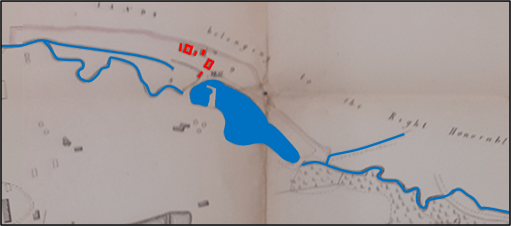

Figure 6, dating from sometime in 1841, is an extract from the Himley Tithe map. It can be seen that there have been some changes. The channel from Coppice Mill pool seems to have been replaced by one leaving the Coppice Mill pool at the north western corner (A), presumably connecting by an underground sough to the new pool on the north side of the Oak Mill pool (B). Alternatively these channels might simply represent construction phase of the new watercourse system that will be described below. This channel is distant from the Coppice Mill buildings and suggests that it is not intended as a channel to feed the mill, but rather to act as an overflow to the Coppice Mill pool, or to increase the flow to the Oak Farm Mill pool. There is perhaps an indication on Figure 6 of a channel corresponding to the mill race position (C), but this is not totally clear. The Oak Farm Mill is again shown by a simple rectangular building – again probably a simple schematic representation.

Figure 6. The Himley Tithe Map from 1841

Figure 7 is an extract from a map that can be firmly dated to April 1849 that shows the whole Oak Farm Estate and may have been produced for when the Estate went on the market in that year. Is shows a similar situation to Figure 6 from 1841, although the shape of the mill pool is different and the small pool to the north no longer appears (perhaps because this wasn’t part of the Estate). The different buildings of the Corn Mill complex are individually shown.

Figure 7. Extract from Oak Farm Estate map of April 1849

Figure 8, produced for the Dudley Estate, has notes referring to the removal of some trees in 1849 and can probably be dated soon after that, perhaps the early 1850s, as the mill pool shape is similar to that of Figure 7.. The Coppice Mill race is clearer (A), and there have been some changes to the shape of the Oak Farm Mill pool (B). The major change, however, has been to the channel from the northern corner of Coppice Mill pool (C) which has now been extended as a surface channel with a sharp turn to approach Oak Farm Mill from a northerly direction (D). This looks to be a new mill race, bringing water from the higher Coppice Mill pool to the Oak Fame mill, which is here shown as a number of separate buildings, with the original mill building to the south. The change in direction would either have meant a complete rebuild of the original mill building to accommodate a new water wheel on its western side, or perhaps the relocation of the mill to the building to the north (the later public house) with a new mill wheel on its western side.

Figure 8. Oak Farm and Coppice Mills in the early 1850s

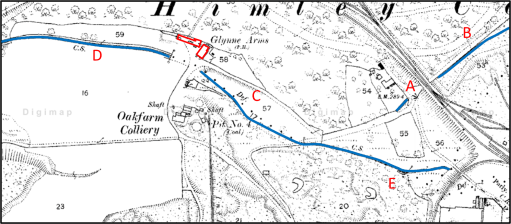

Figure 9 is the Ordnance Survey map of 1882. The situation can be seen to have changed completely with the topography being much changed by mining and other industrial activities and the development of the railway network. The Coppice Mill buildings (A) , and the Coppice Mill pool no longer exists (B), although there is a stream running through its location that runs underground to a junction with Himley Brook. In place of the mill there is a branch of the Earl of Dudley’s railway. Similarly, the Oak Mill pool is now longer visible (C), and the Himley Brook has been channeled, and west of the Oak Farm Mill (now named the Glynne Arms) runs along the old Oak Farm Mill race (D). The eastern end of the Himley brook now presumably runs underground (E). The original (southern) Oak Fam Mill building is no longer visible.

Figure 9. The 1882 Ordnance Survey Map

The 1882 situation is mirrored on the current Ordnance Survey map (Figure 10) and satellite view (Figure 11), where no trace of the mills and mill pools can be seen.

Figure 10. The current Ordnance Survey map

Figure 11. The satellite view from Google Earth

Discussion

The main implication from the above discussion is that it is likely that, around 1841, significant works were carried out on the watercourses in the area, so that Oak Farm Mill was supplied with water from the Coppice Mill pool rather than its own mill pool. The reason for this was straightforward – this would have given a greater head of water, and thus enabled the waterwheel to produce more power for the process of corn grinding. In addition, the larger area of the Coppice Mill pool would have allowed for longer periods of water wheel operation. As there has been much change in the local topography since then due to mining and other activities, it is difficult to be precise about the magnitude of this increase in power, but an estimate can be made from the ground level heights obtained from, for example, Google Earth. The current ground level downstream of the Glynne Arms is around 84m above sea level (asl). Just upstream, in the region where the Oak Farm pool used to be, the current ground level is around 88m asl. At the site of the Coppice Mill the ground level is around 90m asl. The Coppice Mill pool extended beyond Askew Bridge on the road from Himley to Dudley. The ground level on either side of the bridge is around 98m, with the stream under the bridge a metre or so lower. There is thus a very considerable slope from Askew Bridge down to the Glynne Arms – which is of course the reason why two mills were built there. From these heights we can estimate the following.

Water level in race at Oak Farm Mill 84m

Water level in Oak Fame Mill reservoir 88m

Water level in race at Coppice Mill 90m

Water level in Coppice Mill pool 96m

Thus, the head of water available to the Oak Farm Mill was around 4m, and to Coppice Mill was around 6m. The full benefit of these heads would not be available because of head losses in pipes, and sluices etc, but we can estimate the available heads would be around 2m and 4m. Now if the waters in Coppice Mill pool were used to operate the Oak Farm Mill, the potential head available would be 12m. Much of this will be lost by the passage along the new millrace, but it would still be substantial – perhaps around 4m. This represents a doubling of the head available to the Oak Farm Mill, and, as the power is proportion to the available head to the power of 1.5, an increase in power of almost three times. Of course, a considerably bigger water wheel would have been needed to extract this power.

The provision of the Coppice Mill pool water to Oak Farm mill resulted in a ninety degree change in the direction from which the water was coming. As noted above this would either require a major change in the original mill building (the building at the south end of the building complex shown in Figure 8) to accommodate the change of direction and the installation of a larger wheel, or perhaps the construction of a new wheel on the western side of the main building (what was to become the Glynne Arms). Adding speculation to speculation, depending on the type of wheel that was used, this wheel might have rotated in a clockwise direction looking from the west. Now Steve Roughton hypothesized that the main reason for the tilt on the Glynne Arms was due to the soft ground around the original mill raise to the south of the main building. It may thus be that the moment caused by any new waterwheel on the building would have been in the direction to encourage this tilt.

Finally, some further speculation. The early maps show the Oak Farm Mill as a simple rectangular or L shaped building lying to the south of the final location of the Glynne Arms. The current building does not appear on maps in a recognizable form till the 1840s. Thus it may be that the Glynne Arms building was constructed at this period, possibly as a replacement mill when the watercourses were modified. Certainly in the 1841 census, the occupier of the property, John Cartwright was referred to as a farmer, miller and beer house keeper, so the Oak Farm Mill buildings also served as a beer house. That being said, a number of sources give the date of the building of the Glynne Arms as a farmhouse as 1765 – although I do not know the primary source of that date. I suspect it refers to the date when the original mill was constructed.

Whether or not the speculation above has any merit, it is nonetheless clear that in the early 1850s, major construction work was carried out to increase the supply of water to the Oak Farm Mill, but that the new water courses were all swept away as heavy industry spread across the area in the later 1850s and 1860s.