The recent burning down and demolition of the Crooked House public house in Himley in August 2023 has made news both nationally and internationally, and there are ongoing police investigations into the events and a vociferous campaign for rebuilding. In all the reporting, however, there has only been limited discussion of the history of the Glynne Arms, as it was formerly known. It is the intention of this post to fill in this gap, in terms of the early history of the property, up to around 1880. I feel this is important, as it gives something of the background and context that is perhaps somewhat lacking in the current conversations.

Figure 1 shows a modern Ordnance Survey map of the area. The Crooked House is indicated by a red circle on this figure and the ones that follow, which, unless otherwise stated, all show the same area to the same scale. The site of the Crooked House is situated on the north bank of the Himley Brook that flows east to west from the Old Park / Russell’s Hall area to the River Smestow, at the end of a mile long lane that leaves the Himley to Dudley Road just to the east of Askew Bridge (A). Footpaths from the site go north through Himley Wood (B), and south across an area of reclaimed industrial land (C) and the old GWR Kingswinford branch line (D) to Oak Lane (E), where there are various small-scale industrial businesses. But the area that we see now is very different from how it would have looked a hundred years ago, which itself was very different from how it would have looked a hundred years before.

Figure 1. Location of the Crooked House on a modern Ordnance Survey map

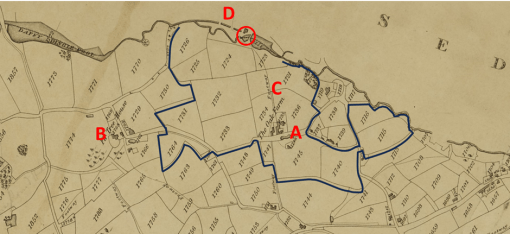

The Crooked House was built in 1765, probably as a corn mill, and first appears in the records on the 1822 Fowler map of Kingswinford parish (figure 2). The Himley Brook was the boundary between the parishes of Kingswinford and Himley, and the Crooked House, being to the north of the brook, was in Himley Parish, and thus its appearance on the Kingswinford map is quite fortuitous. At the time it was part of the Oak Farm Estate owned by Lady Mary Glynne of Hawarden in north Wales, that had been bequeathed to her and her husband by her father on her marriage to Rev Stephen Glynne in 1779 (Davies R (1983) “The Great Oak Farm smash”, Blackcountryman 16.3, 18). The estate consisted of around 90 acres of farming land mainly in the north of Kingswinford parish, with small areas in Himley and Sedgely parishes. The names of the fields give an indication of its rural character – for example Barn Close, Coppice Piece and Ox Ley. The land to the north of the Crooked House was part of the Dudley Estate and was a mixture of arable and coppiced woodland. The figure shows the boundary of the estate, Oak Farm itself (A), Fir Tree House outside the estate owned by Lord Dudley (B) and the footway from Oak Farm to the Crooked House (C). At the time, the Oak Farm estate was largely farmed by Richard Westwood, who lived at the Oak Farm. The Crooked House was at this stage, clearly a mill, and the mill race can be seen on the map passing beneath the house (D). There would have been a waterwheel operated by the water from the pool on the Himley Brook to the east, with the water being returned to the brook along the mill race. The road network at that time was very different from the modern network, although Stallins Lane and its predecessor can be seen in the bottom right-hand corners of both figures 1 and 2.

Figure 2. The Crooked House on the 1822 Fowler map of Kingswinford Parish

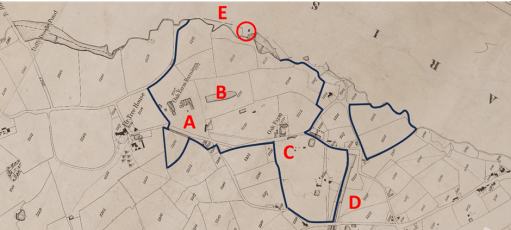

The next occurrence of the Crooked House in the historical record comes from the Tithe Apportionment records and maps in the early 1840s. The maps for Kingswinford and Himley parishes are shown in figures 3a and 3b. Note that the alignment to north is not quite consistent between the maps – the originals of both were aligned in somewhat arbitrary directions and alignment was not straightforward. In some ways the situation was very similar, with the surrounding countryside still very rural. But change was underway. The Oak Farm estate had passed to Lady Glyne’s son, Sir Stephen Glynne and in 1835 he and his partners had begun to exploit the large reserves of coal, ironstone and clay that had been found there. In the tithe allocation the estate is said to be owned by the Oak Farm Colliery Company, with the owners of the company being Thomas Bagnall, James Boydell, Baronet Sir Stephen Glynn, John Hignett, William Hignett and Charles Townshend. Already there were the Oak Farm furnaces to the south of Himley Brook (A and B), together with at least three coal pits and three ironstone pits and the associated pumping engines (C). The northern end of the Stourbridge Extension Canal can be seen on Figure 3b (D). The boundary of the estate is also shown and, whilst it remains substantially the same as in 1822, there have been some changes in the region of the Extension Canal. The somewhat reduced area of arable land (57 acres) was farmed by several tenants, with the majority (50 acres) by John Cartwright who was based at the Crooked House. In the 1841 census, his age is given as 62 and he is described as a miller, farmer and beer shop keeper. He was living with his wife Sally, aged 56, and three domestic servants. The mill race can again be seen on both maps (E). Again, the road network can be seen to be different to the current network, with the current long lane to the Crooked House not appearing.

a) Himley Tithe map

b) Kingswinford Tithe map

Figure 3. The Crooked House on the Kingswinford tithe map and the Himley tithe map

The fate of the Oak Farm company is well documented elsewhere – there seems to have been a major lack of financial control, probably to an over rapid expansion by James Boydell, who was in charge of the management of the company, that led to a level of debt that could not be serviced. The firm went bankrupt in 1849, and all its very considerable effects were put up for sale. This included

…. that conveniently situated and commodious dwelling-house, now used as a Public-house, with the garden, stabling, outbuildings and appurtenances, and water corn mill, now in the occupation of Mr. John Cartwright……

The whole estate was eventually bought by the future prime minister William Gladstone, Stephen Glynne’s brother, Stephen Glynne himself and his brother Rev Henry Glynne. It took many years, and a great deal of money, for Gladstone to resolve the financial issues of the Oak Farm concern and the other Glynne Estates, but the Oak Farm works began to prosper. However, by the 1860s and 1870s the mineral resources in the Oak Farm area were beginning to fail, and on the death of Sir Stephen in 1874, the family finally sold the estate.

During this period, the Crooked House no doubt continued as a corn mill whilst there was any arable land left to produce grain, but also came to serve the coal miners and iron workers of the area. In the 1851 census, it is simply referred to as Himley Oak Farm Mill, run by Sally Cartwright, aged 66, John’s widow, who also farmed 30 acres (note the reduction from 1840). Her son Joseph (aged 26) was the miller. It is interesting to note that Sally sister, Fanny Amis, aged 74, also lived with them. In the Directory to the Fowler map of 1822 she is recorded as being responsible for the Hollies Farm in the Old Park / Russell’s Hall area.

By 1855, the Crooked House, now referred to as the Glynne Arms for the first time, was run by George Wilkinson, importer of foreign wines and spirits, and cigars. In the 1861 and 1871 censuses however, the pub was run by Joseph Woodcock, and his family.

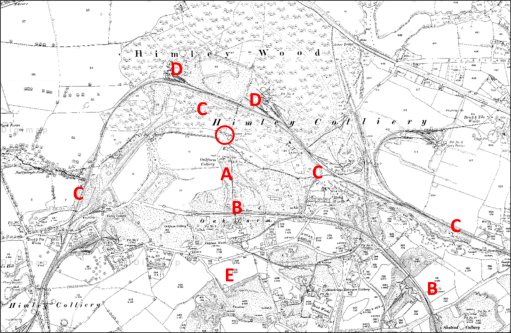

During the period of the Oak Farm concern rise and fall, the area around the Glynne Arms changed out of all recognition. Figure 4a shows the Ordnance Survey map of 1881 to the same scale as figures 1 to 3, whilst figure 4b shows the area around the Glynne Arms to a rather larger scale. The area to the south of Himley Brook had been extensively mined and the map shows the location of the Oak Farm Colliery and large areas of colliery waste (A). And the pub now seems to be surrounded by railway lines – the GWR Kingswinford branch to the south (B), at this time terminating in the Oak Farm area, and the complex tangle of lines of the Earl of Dudley’s Pensnett railway to the east, north and west (C). There are extensive railway sidings and collieries within Himley Wood itself (D). Very little undisturbed land remains. The mill pool has been drained, and the Himley Brook diverted, possibly along the mill race. A comparison of figures 1 and 4 does however show that the road network is approaching its final form and route of Oak Lane is very similar to the present and the long lane from the Himley Road to the Glynne Arms can also be seen, at least in part (E). The access still seems to be from the south however, showing that it was very much part of the Oak Farm estate.

(a)

(b)

Figure 4. The Crooked House on the 1881 Ordnance Survey map

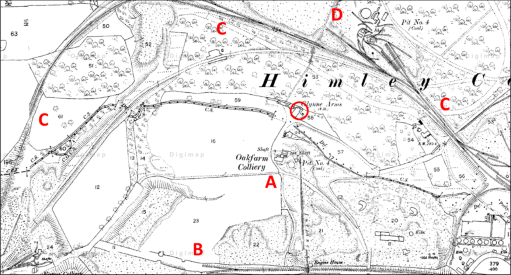

Figure 5 is taken from the Coal Authority web site and shows the mine entries that have been documented around the Crooked House. The cluster to the south of the Himley Brook (A) were part of the Oak Farm Collier and were in use from the 1860s to 1880s, and if mining subsidence caused the Crooked House to take on its iconic character before its destruction, the mines in this area are the cause.

Figure 5 Mine entries in the area of the Crooked House

In conclusion then, it is clear that the early history of the Glynne Arms / Crooked House was bound up with the development and tribulations of the Oak Farm Estate, and there was a gradual transition from its role as a Corn Mill to that of a Public House. It may be that, should the remaining foundations of the Crooked House ever be investigated as part of any rebuilding that some interesting archaeological remains might be found, pertaining to the corn mill (perhaps the wheel pit or supports, and remains of the mill race).

Extremely interesting thank you.Although I knew much of this, I have also learned a lot.

Best wishes

<

div>Clive Corbett

Sent from my iPhone

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

Have you considered sending this to the Bugle?

<

div>Clive

Sent from my iPhone

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

Bit too technical for the Bugle I think, but might look elsewhere

LikeLike

I understand very good though

Sent from my iPhone

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

Great great article as always! You should try to get this published in a local newspaper as interest in the Crooked House is very high at the moment!

LikeLike

Love this article. And I can tell you that in the cellar under the part where the wheel would of been (if attached to the house) there as a blocked area where I presume workings of the mill could still be there!!

LikeLike

Thanks. Also have a look at this blog post by Steve Roughton on the Black Country Society site – https://www.blackcountrysociety.com/post/what-really-caused-the-crooked-house-to-tilt. (Posted by me as the webmaster for the Society)

LikeLike