Brettell confusion

In the writing of Kingswinford Manor and Parish (KMAP), one of the loose ends was the Brettell family, who were clearly important in the area and married into other major families, but who were very difficult to trace through the historical record, not least because they seemed to have used a very small set of Christian names, with all the confusion that implies. This issue was particularly acute when I considered the Fowler Maps of Kingswinford of 1822 and 1840. In the former we have at least one Thomas Brettell and at least one Benjamin Brettell, and in the latter we have Anna Maria Brettell and Penelope Brettell – all holding quite significant portions of land.

A reader of KMAP, Keith Evans, seeing my confusion, has come to my help. In his family tree studies he has identified the following Brettells in late 18th and early 19th century Kingswinford that are of relevance.

- Benjamin Brettell (1720-1793) who married Elizabeth Jeavons in 1763, where he was identified as a Malster. He is later referred to as a Coal Master.

- Benjamin Brettell (1764-1822), the eldest son of Benjamin and Elizabeth, who was apprenticed to Richard Mee of Himley in 1780 and became an attorney. Two children are mentioned in his will – Benjamin and Anna Maria.

- Thomas Brettell (1769-1835), another son of Benjamin and Elizabeth, who married Penelope Antrobus Cartwright, and was recorded as a Coalmaster. Two children are again identified, Benjamin and Elizabeth.

Using the above as background information, we can consider the Brettells identified in the Directories for the Fowler maps of 1822 and 1840 in a little more detail.

Brettells on the Fowler Maps

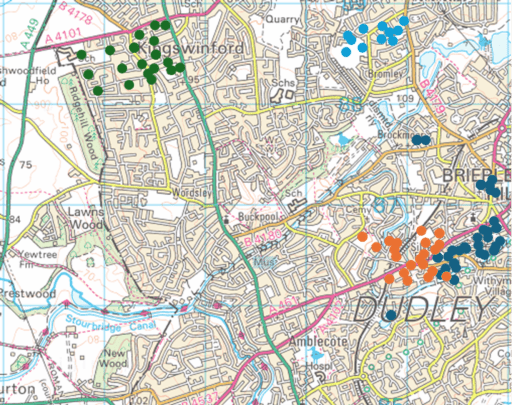

Figure 1. The Brettells on the 1822 Fowler Map – Brown circles – Thomas (Brettell Lane); Dark blue circles – Benjamin; Green circles – Thomas (Summerhill); Light blue circles – Thomas (Tiled House)

In 1822, there were four clusters of land that were either owned or occupied by a Brettell (Figure 1, which shows those plots of land owned or occupied by Brettells, superimposed on a modern map).

- Those lands owned by Benjamin Brettell at the upper end of Brettell Lane and in Brierley Hill and Brockmoor. These were, as far as can be judged, in the area that was enclosed by the Pensnett Chase Enclosure Act of 1784 and allocated to Benjamin Brettell Senior.

- Those lands owned by Thomas Brettell along Brettell Lane. These adjoin those of Benjamin, but are on land that was not enclosed in 1784 i.e. land that was either an old enclosure or a more formal old estate.

- Those lands owned by Thomas Brettell in Summerhill, including Summerhill house where he resided. These were in the area where the 1776 Ashwood Hey Enclosure Act formalised informal enclosures of 1684, so this block of land probably originates in this period.

- The Tiled House Estate occupied and inhabited by Thomas Brettell, but owned by Richard Mee (the son of the Richard Mee to whom Benjamin junior was apprenticed).

The blocks of land in the Brettell Lane area were not continuous, and werei nterspersed with lands owned by others.

The immediate question is whether or not all these lands were owned by the same Thomas Brettell. The Thomas Brettell at Summerhill is sometimes styled in the Directory of the 1822 Fowler Map as “Esq.” which may differentiate him from the other Thomas’s. Against that is the fact that some of the land was occupied by Benjamin Brettell, either Thomas’s brother or his son. It is of course possible there might have been another Benjamin, but this does tend to suggest that the same Thomas owned lands in Brettell Lane and in Summerhill. If that is the case, then this Thomas would have no need of the Tiled House as a place to live in and one must conclude that the Thomas who lived there was not the same Thomas who held lands in Brettell Lane and Summerhill. All very confusing.

The other point that can be made is that the fact that Thomas and Benjamin’s lands along Brettell Lane adjoin each other suggest that in the previous generation (i.e. Benjamin Senior) they were one land unit.

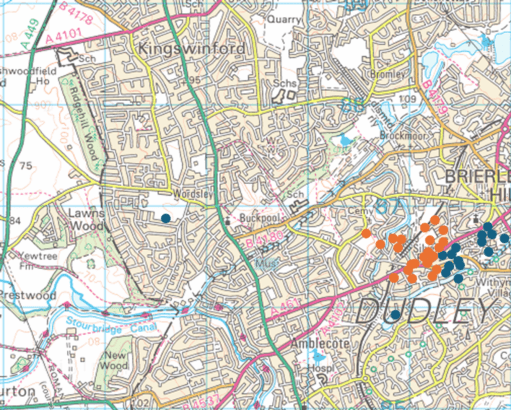

Figure 2. The Brettells on the 1840 Fowler Map – Brown circles – Penelope; Dark blue circles – Anna Maria

In 1840, it is clear from Figure 2 that all Benjamin’s lands went to Anna Maria and all of Thomas’s Brettell Lane lands went to Penelope. Thus one must conclude (along with Keith Evans) that Anna Maria was Benjamin’s daughter and Penelope was Thomas’ widow. At that time the Summerhill estate was in the hands of Revd. Henry Hill, a cleric from Worcestershire. He rented these out to be farmed, mainly by the large farming firm of John Parrish and Co.

A ghost from the past

The name Brettell seems to originate from Bredhull, or broad hill, in the early middle ages. This seems to have been centred on Hawbush along Brettell Lane, a little to the south west of the land holdings of Thomas were in 1822 (Figure 1). Is it too fanciful to speculate that what we have here is a ghost of an old estate, with much of the land sold to others? We know that such estates existied in the north of Kingswinford parish – Oak Farm, Shut End, Corbyn’s Hall, Tiled House and Bromley House) and perhaps here we have a southern counterpart. It would be unwise to take this speculation much further, ut it is, perhaps, and intriging possibility.