Introduction

As the journalist Christian Wolmar has discussed in a recent article, the UK does not have any sort of agreed National Transport Policy that could be used as a rational way of developing transport infrastructure in a politically non-partisan way. Such a policy will certainly not emerge from the current government, and there is little to suppose that any future government will give priority to developing such a plan. Without it, transport policy is vulnerable to ill thought-out ad hoc initiatives and, as at present, in ad hoc cutbacks. In this post I will suggest a pragmatic way forward on this.

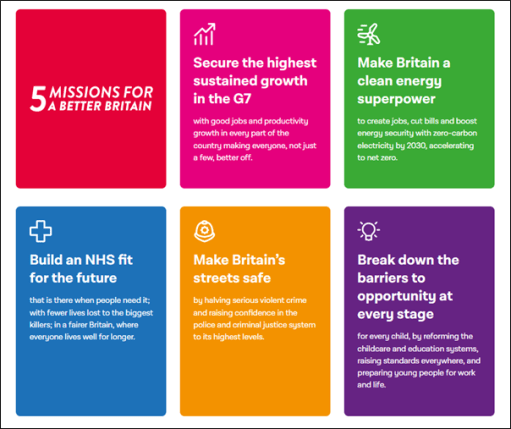

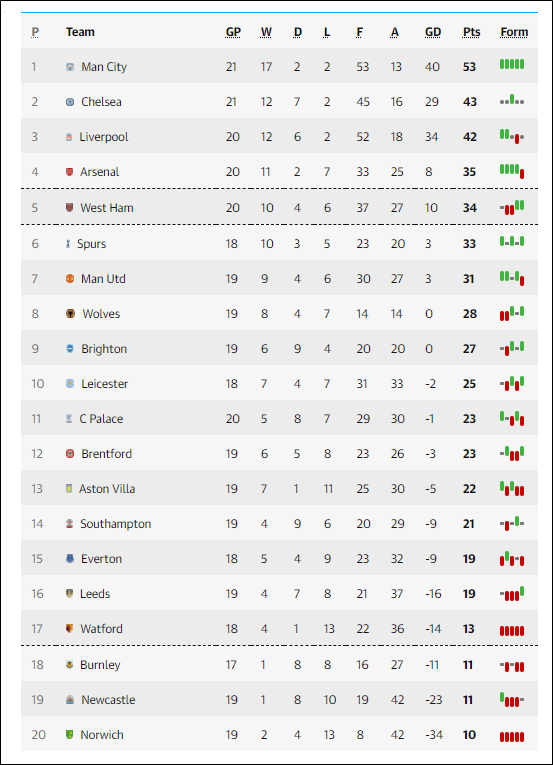

What I propose is based on the assumption that the next Government will be formed by the Labour Party, either as a majority party or with some sort of agreement with the Liberal Democrats. This is certainly what would be suggested by the opinion polls where at the time of writing Labour have a 22% lead over the conservatives. The Labour party has proposed five “missions” that will direct their approach to the 2024 elections and any subsequent government. None of these missions mentions transport at all, but there are transport issues embedded in each one of them. In what follows, I set out these missions, the transport issues that arise from them, potential policy objectives, and potential policy proposals. I then bring these proposals together to form a list of Transport policies that could be used, no doubt in a modified format, both for the next election and in any subsequent government.

Readers should not assume from this that I am a Labour Party supporter. I have never been a member of a political party, and never intend to be. Politically I am a centrist, but with somewhat radical environmental views, formed partly by my professional work as a Professor of Environmental Fluid Mechanics at the University of Birmingham (now retired). The proposals below are simply pragmatic – a possible way of influencing the next government to do something sensible in transport terms.

The Labour Part Missions

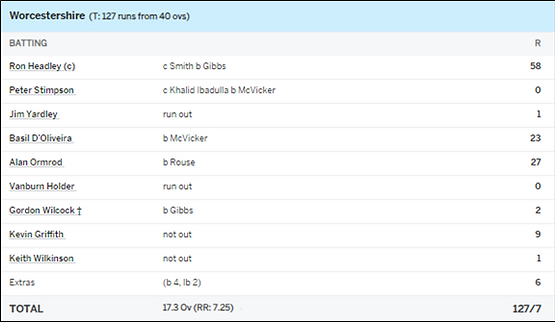

Mission 1

Secure the highest sustained growth in the G7, with good jobs and productivity growth in every part of the country making everyone, not just a few, better off.

Transport issues

- Transport congestion on road and rail, for both people and products, leading to reduced productivity.

- Poor workforce mobility, leading to inflexibility in employment locations.

- DfT methodology for assessing CBR of transport infrastructure does not take proper account of induced flows on highways – i.e. new roads encourage traffic growth and can increase congestion.

Transport policy objectives

- Revise DfT methodology for assessment of congestion reduction of new roads to include induced flow effects.

- Infrastructure interventions to reduce road and rail congestion.

- Encouragement of modal shift from road to rail, for both people and products.

Transport policy proposals

- Revision of DfT methodology for assessing congestion reduction of new road schemes to include proper consideration of induced flow.

- Small number of specific congestion-reducing road schemes (consistent with Mission 2).

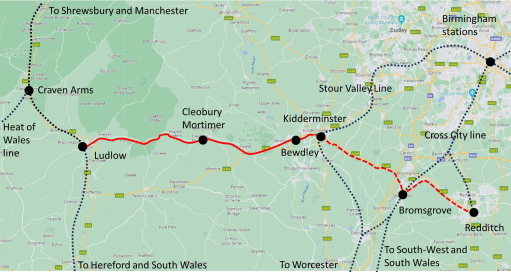

- Speed up development of rail enhancements and new build (HS2, EWR and NPR).

Mission 2

Make Britain a clean energy superpower to create jobs, cut bills and boost energy security with zero-carbon electricity by 2030, accelerating to net zero.

Transport issues

- DfT methodology for assessment of contribution new transport schemes to carbon production and climate change has been shown to be flawed, particularly in relation to new roads.

- UK Carbon based transport emissions levelling off or increasing.

- Transport is now major carbon producing sector of economy.

Transport policy objectives

- Reassessment of DfT methodology for assessing environmental impact and carbon production of new transport schemes.

- Development and roll out low carbon technologies (electric and hydrogen vehicles, electric trains) including electric car recharging infrastructure.

- Encouragement to use low carbon modes of transport and active travel modes.

Transport policy proposals

- Revision of DfT methodology for assessing environmental impact of new road schemes to be revised.

- Investment in electric and hydrogen vehicle research and production

- Development of electric vehicle recharging infrastructure.

- Electrification programme for railways

- Fiscal incentives to encourage low carbon mode use.

Mission 3

Build an NHS fit for the future by reforming health and care services to speed up treatment, harnessing life sciences and technology to reduce preventable illness, and cutting health inequalities.

Transport issues

Transport policy objectives

- Improve urban air quality through encouraging low emission vehicles.

- Improve air quality through traffic reduction and modal shift to public transport.

- Encourage active travel (cycling and walking).

- Improve public transport (primarily bus) links to health care facilities,

Transport policy proposals

- Fiscal incentives for ULEZs and LTNs.

- Support for public transport

- Fiscal incentives to local authorities to provide active travel infrastructure.

Mission 4

Make Britain’s streets safe by reforming the police and justice system, to prevent crime, tackle violence against women, and stop criminals getting away without punishment.

Transport issues

- Safety issues due to high road speeds in urban areas.

- Safety issues due to pavement parking.

Transport policy objectives

- Make urban streets safe for pedestrians and cyclists.

Transport policy proposals

- Fiscal incentives for LTNs.

- Lower and enforce urban speed limits.

- Enforce pavement parking laws.

Mission 5

Break down the barriers to opportunity at every stage, for every child, by reforming the childcare and education systems, raising standards everywhere, and preparing young people for work and life.

Transport issues

- Poor access to childcare and education for those without cars (20% of households)

Transport policy objectives

- Improve access to childcare and education for those without cars.

Transport policy proposals

- Support for public transport

- Fiscal incentives to local authorities to provide active travel infrastructure.

The policies

From the consideration of the individual missions, the following specific transport policies can be developed.

Policy 1

Revision of DfT methodologies for assessing new transport schemes to take proper account on induced flow and environmental effects. (Missions 1 and 2)

Policy 2

Invest in new transport infrastructure with a small number of congestion-relieving road schemes, electric car charging facilities, and major investment to rail infrastructure, including staged development of HS2, NPR and EWR) and a rolling programme of electrification. (Missions 1 and 2)

Policy 3

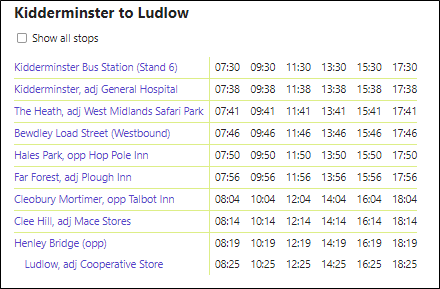

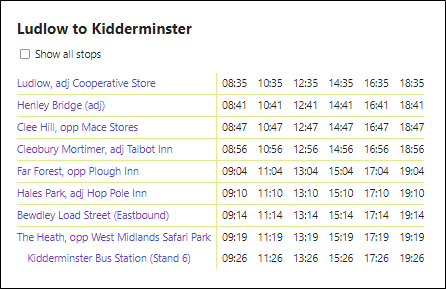

Support for public transport (trains and buses) for increasing employment opportunities and providing access to healthcare and education. (Missions 1, 3 and 5)

Policy 4

Reduction of urban speed limits and enforcement of pavement parking laws. (Mission 4)

Policy 5

Fiscal incentives and support to local authorities to encourage low carbon vehicles and modal transfer to low carbon modes; for the development of ULEZs and LTNs, and provision of active travel infrastructure. (Missions 2, 3 and 5)

Commentary

Policy 1 is not going to set any electoral debate alight, but it is quite crucial. In the past the DfT has used flawed policies to assess road building schemes against other transport schemes, knowing that they were flawed. This needs to change. Indeed, I would regard the DfT as no longer fit for purpose in many ways (as an example, its current handling of the railway network, the ongoing industrial action and major cutbacks to active travel budgets can be cited) and there is an argument for a complete re-organisation here to establish a wide ranging Department for Infrastructure that brings together transport, the utilities and construction. This would allow proper consideration to be given to the transport effects of new housing build (often built without public transport provision) and conversely the effect of a move to electric vehicles on the development of the electricity grid.

Policy 2 is wide ranging and expensive, and any specific proposals would need to be carefully phased in terms of expenditure. The basic point however is that high quality transport infrastructure for people and products is a fundamental requirement for a productive economy, the more so as the switch to the “green economy” proceeds.

Policy 3 is important for many, and in particular those on low incomes. The provision of a high-quality public transport network (particularly buses) that is comprehensive in its coverage would make access to employment, healthcare and education very much easier for many people.

Policy 4 is essentially aimed at public safety. It would no doubt be categorised as a “war on motorists” by sections of the press, but this is a battle that needs to be fought for the public good.

Policy 5 is another proposal that might be electorally contentious as (weirdly to my mind) LTNs, ULEZs and active travel have become very politicised. Fiscal incentives could be a way forward here, as proposed in the more detailed description of Mission 2 recently released by the Labour Party. This might include the possibility of both support for the initiatives and a wider reduction in rates for those Local Authorities that develop such schemes. This would be basically a bribe, and would need to be carefully costed and targeted, but could help in the establishment of such schemes. In terms of encouragement to use low carbon modes, a study should be initiated to look at how road pricing, aviation fuel duty and rail fares could be used to encourage the necessary modal shift.