Introduction

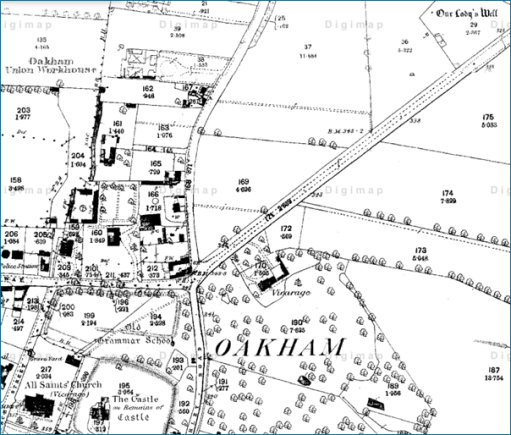

In this series of three related posts, I present transcripts of the press reports concerning the re-opening of All Saints church in Oakham in November 1858. This is done primarily to make the source documents for that event available and easily readable, and there is no discussion of their contents. That will come later. The material is all found in the British Newspaper Archive and the archive OCR text forms the basis of the transcripts, although. As with any OCR text, this has needed considerable editing, which, as I am sure the reader will find, has been imperfectly done. The material presented in the three parts is as follows.

- Part 1 contains the notice of the re-opening the from the Leicester Journal of 5th November 1858 and a report on the event itself from the Stamford Mercury of 12th November 1858. The latter contains the text of the report by Gilbert Scott that describes the state of the church before the restoration and what, in his view, needed to be done.

- Part 2 contains a report of the opening from the Leicester Journal of 12th November 1858. This covers some of the same ground as the Stamford Mercury report, and whilst not including Scott’s report, does give details of the opening event, including the sermon that was preached.

- Part 3 (this part) is from the Lincolnshire Chronicle of August 24th 1860, and gives the text of a lecture that was given at Oakham Castle entitled “Gothic Architecture” by the Rev Canon James, one of the principal proponents of the Gothic in the region, where the changes that were made to the church are explained and justified.

Leicester Journal 12th November 1858

Amidst the numerous church restorations which have recently been made in this county and district, the one at Oakham is certainly one of the most complete and perfect every detail. The church had for some time past fallen into a sad state of decay, and the worthy vicar, the Rev. Heneage Finch, determined, with other friends, if possible, to restore the fabric throughout, besides giving more seat accommodation. The old fashioned, high-backed pews, and west end gallery having long proved inefficient for the requirements of the parish, it was determined once to remove them. After some delay, sufficient sum was raised by subscription to warrant the commencement of the work, Mr. G. Pinch having headed the list with the handsome sum of £1000, the Vicar and others also contributing largely.

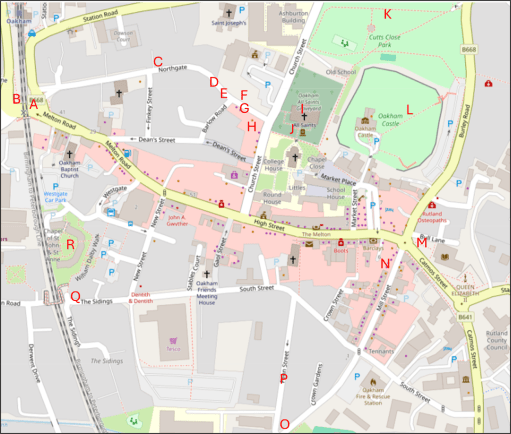

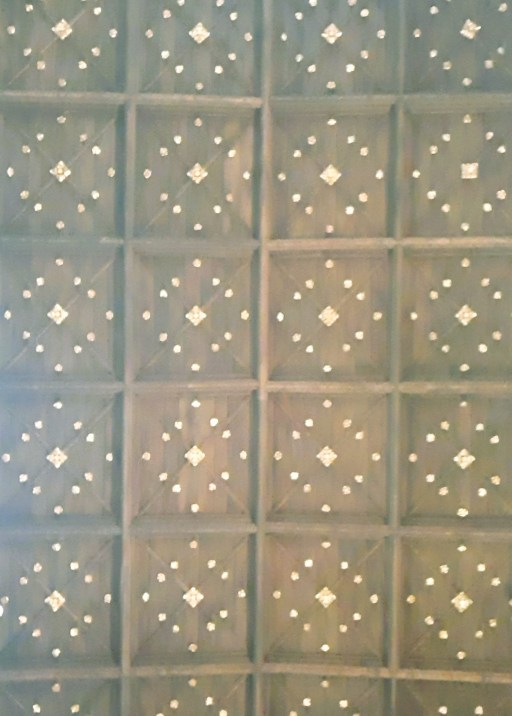

The church itself is mostly in the Perpendicular style, having been built in the 15th century, and is considered to be the finest specimen of ecclesiastical architecture in the county. The roof had fallen into a fearful state of decay and has been thoroughly restored. The Chancel has had entirely a new roof, composed of English oak, very richly panelled in the Decorated style, and contains some very fine tracery. The groundwork of the altar consists of very fine traceried carved bosses, which has a fine appearance. The nave, aisle, and transept have also been entirely restored with English oak. The south chapel has an exceedingly beautiful ceiling in oak, enriched with moulded ribs and carved bosses intersections, with traceried panels. The whole of the roofs are covered with new lead, the old being entirely removed. The western entrance, which was formerly blocked up, only being used the ringers, is now made the principal entrance. The first stage of the tower has now a new ringing floor, and the bells, which are six in number, have been re-hung in new oak frames. Two of the bells have been re-cast by Mears, of London. A new clock is also in course of erection, by Dent, of London, which is to have two faces, one looking south and the other west, and is to strike the quarters. A new east window of five lights has been put into the chancel, glazed with diamond quarries of cathedral glass, with cast-iron saddle bars. The shafts of this window are of fine Derbyshire polished marble. The interior of the church has undergone a thorough reseating, open seats having (as before stated) been substituted for pews, whereby 300 additional free sittings have been gained for the poor. The seats are made of the finest wainscot oak, with moulded ends, having carved terminations. The low screen dividing the chancel from the nave, is also of oak, filled with open tracery, richly carved. The pulpit, which is also of oak, is supported by a bracketed pedestal, the panels being filled with rich tracery. The north and south screens, separating the aisles from the chancel, have very rich moulded tracery and embattled cornices. The stalls in the chancel, and reading desks are exceedingly rich in detail, having foliage, representing the holly, oak, vine, and hop, beautifully carved on the terminations. The altar-rail is also of oak, with lozenge-formed compartments, and the table itself is of massive oak, supported on six octagon shafts, richly moulded. The old South doors have also undergone a thorough restoration, according to their original features, and are of a very massive character. The West and North doors are of oak, framed in small compartments, covered with rustic bordering, with ornamental hinges, &c. The body of the church is laid with black and red Staffordshire quarries, and the chancel and sacrarium are paved with Minton’s encaustic tiles, from designs furnished by the Rev. Lord Alwyne Compton, and are exquisitely beautiful. The south side of the sacrarium is furnished with a credence table in Caen stone. The glazing is entirely new throughout the church, the windows being all filled in with cathedral glass of a light green tint, and of a small lozenge pattern. Ail the stonework has been thoroughly cleaned from whitewash, and brought to its original colour, as well as entirely restored. The old stoves have been done away with, and a new apparatus on the most approved principle of warming by water, has been erected by Messrs. Rosser, of Millbank-street, Westminster. The church is beautifully lighted with rich metal gas standards, of 20 jets each, the two chancel lights being extremely elegant in design and workmanship, every alternate burner forming a star. They were supplied by Messrs. Skidmore, of Coventry. The whole of the woodwork and carving has been done by Mr. Ruddell of Peterborough, in his usual style of excellence; and the masonry has been executed in a very superior style by Mr. Thomson, also Peterborough. Both these gentlemen were the contractors for St. George’s Church at Doncaster. The total cost has been between six and seven thousand pounds, the whole having been subscribed, with the exception of about £300. We had almost forgotten to mention that the old Norman font, which is evidently older than the present church, has been cleaned and restored, and refixed at the west entrance. The whole the work has been carried out under the direction that talented ecclesiastical architect, G. G. Scott, Esq., of Spring Gardens, London; and Mr. Geo. Clarke, clerk of the works of the Lichfield cathedra], has had the superintending of the works.

The re-opening of the church was fixed for Wednesday and Thursday last. Morning service commenced Wednesday, at 11 o’clock, when the church was filled a very large congregation, the admission up ten minutes to eleven being ticket only. At eleven o’clock a procession was formed from the new grammar-school to the church, in the following order:

Sexton

Choir boys

Choir

Committee

Churchwardens, Messrs. Davis and Ratcliffe

Clergy in gowns

Clergy in surplices – Rev. W. L. Wood, Rev. W. King, Hon. and Rev. A. G. Stuart, Rev. Thos. Yard, Rev. Heneage Pinch, and Rev. E. Meyrick Goulbourn.

The clergymen in the procession numbered about 50.

The choir of St. John’s church, Leicester, attended, and Herr Schneider, organist of St. John’s, presided at the harmonium, there being no organ at present.

Morning prayers were read by the Rev. W. Wingfield, assisted the Rev. R. Sorsbie, the Rev. W. J. Wood, the Rev. Heneage Finch, the Rev. J. R. Woodford, the Rev. A. 0. Stuart, and the Rev. T. Yard. The offertory was read by the Rev. J. R. Woodward.

Amongst those who were present we noticed the Hon. H. Noel and party, Hon. Colonel Lowther and party. Lord Wensleydale, Mr. George and Lady Louisa Finch, Sir John and Lady Trollope, Sir R. Sheffield, Edwd. Cayley, Esq. (Stamford), W. A. Pochin, Esq., W. Rudkin, Esq., W. Sharrard, Esq., J. Painter, Esq., Mr. Buftress(Wymondham),. Messrs. Wellington (Oakham), Hawthorn (Uppingham), the Rev. H. Finch (vicar). Dr. Goulbourn, Hon. and Rev. A. G. Stuart, Rev. Thos. Yard, Hon. and Rev. Leland Noel, Rev. Thos. James, Rev. J. R. Woodford, Rev. W. S. Wood, Bev. R. King, Rev. C. A. Stevens, Rev. C. E. Pritchard, Rev. Nowell Twopenny, Rev. C. H. Atlay, Rev. H. Wingtield, Rev. R. Sorsbie, Rev. J. W. Skevingham. Rev. J. H. Milne, Rev. G. E. Gillett, Rev. H. J. Rev. G. A. Poole, Rev. C. E. Prescott, Rev. J. H. Noyes, Rev. Lovick Cooper, Rev. S. E. Gretton, Rev. Si, G. Bellairs, &c.

The sermon was preached by the Rev. Dr. Goulbourn. of Quebec Chapel, Loudon, from the 3rd chapter of Exodus, and the 5th verse “ Draw not nigh hither, put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground.” The rev. gentleman said, in the passage he had just read was wrapt up the doctrine of sacred places. Now, what was a sacred place – in what sense could one place be more sacred than another No doubt the popular answer would be, that wherever Christ was present was sacred. Now such a meaning would have the strictest sanction of scripture. It was true that the Lord Jesus was present in every Christian congregation, but was it not also true, that God was present in every district of the universe? Go where you would, you could not escape from Him; He was there. If he scaled the tops of the highest mountains or descended into the bowels of the earth. He was there also. If he took the wings of the morning and remained in the uttermost parts of the seas. He was there. God was present everywhere. How then did it come to pass that such passages as these harmonised with what had been said that his presence was limited to certain places? The answer was very simple. When God was spoken of present certain places. His manifested presence was meant. The definition of sacred place was, where God manifested Himself the eye of the body or the eye of the mind. The rev. gentleman then went on to speak respecting the consecration of churches. He said, as regarded the consecration of a building, it did not make it, it only recognised it as holy. Just the coronation of king did not make that person king, for he was king soon as the breath had left the body of his predecessor; it only made him responsible for his office. In the same way, when a church was consecrated it could only be used for sacred purposes, and the building was made sacred in the truest and highest sense of the word. The ordinary manifestation of the Divine Being was made in the Church. He would now turn to the extraordinary. He then instanced the appearance of the angel to Joshua, and Jacob’s vision, as extraordinary manifestations. But it was not accordance with our new dispensation that such manifestations should now be carried on; yet God manifested himself in Christ even now to the conscience and heart of the true Christian. This was a much higher manifestation than the preceding one. It was the manifestation of Christ through the agency of the Holy Spirit which impressed the house of prayer with that sanctity which possessed. The rev. gentleman then went to refer to the practice that was required be adopted holy places under the old dispensation, The custom was to take off the shoes, on entering a sacred plane, to show allegiance to God; but the custom in our day was different. Instead of uncovering the feet, we uncover the head. The postures also should be distinctly preserved, standing and kneeling at the proper time. This should be attended by all, except those who are prevented by age or bodily infirmity. All communication with each other while in church should avoided milch possible. But the most important point of outward reverential conduct, was to join in the service in an audible voice. It was not at all proper to lay the burden upon few; but let them all join together seeing that the service of prayer and praise, in which they all had common interest, were properly carried out. Let it not thought that this class of duties were as trifling they might seem first sight. They rested upon the purest and most important principles. Man was bound to yield to God the homage of bis entire nature; and the homage of the body ought to be subservient to that of the spirit. But if they merely bowed the head, and had no corresponding feeing at the heart, It was the worst of mockeries. The rev. gentleman concluded bis sermon, of which this is the merest outline, by some observations respecting the restoration of the church. He said great advantages had been rained the alteration, and this above all others, that several hundred free sittings had been secured for the use of the poor by the substitution of open seats for pews. To see a church choked up with high pews, only occupied the higher classes, could not but be revolting to every right mind. But now the case was different; rich and poor could all worship together without any distinction. All grades ought to be on a level while in church. He was sure it must be highly gratifying to those persons who had subscribed towards the alterations, to think that they had been the means of contributing something towards affording greater accommodation for the population of the parish. But the same time there was a deficit on the restoration fund of about £300, which he hoped they would remove.

At the close of the sermon, a collection was made, and the handsome sum of £174. Is. 6d. obtained. At the afternoon service, the church was again filled with a respectable congregation. Prayers were read the Rev. M. Wingfield, Rev. Robt. Sorsbie, Rev. Timothy and the Rev. J. A very impressive sermon was preached by the Rev. Canon James, of Theddingworth, who took for his text the 11th chapter of St. Luke, and the 25th vers ” And when he cometh, he findeth it swept and garnished.” At the close, the sum of £31.7s 1 ½d was obtained.

Services were to be held yesterday (Thursday), and also next Sunday, but we have not been able to obtain the amount collected.

We might mention that every accommodation was provided for visitors, refreshments being set out the Agricultural Hall, which was thrown open for free inspection during the day.

On Friday night last, the committee, contractors, and workmen to the number of 60, supped together in the Agricultural Hall, Mr. B. Adam, solicitor, Oakham, presiding, supported by Mr. Wellington and Mr. Mortin. The usual loyal toasts were given, and the health of the Bishop and Clergy of the Diocese was very ably responded to by the Rev. W. S. Wood, head master of the Grammar School.