Preamble

The study of local history is often a very personal affair. I recently moved from Lichfield to Oakham in Rutland, and have thus naturally become interested in the local history of the area, about which I previously knew very little. In particular the early, pre-Domesday, history of the area intrigues me. The nature of the now the county of Rutland in that period is far from clear. At Domesday in 1086 (1), it was divided between “Roteland” – the two northern wapentakes of Alstoe and Martinsley, which were recorded as a detached part of Nottinghamshire, and the southern hundred of Witchly, which was part of Northamptonshire (Figure 1 – from (2)). In a detailed study Phythian-Adams (3,4) argued that there was a deeper underlying unity and that Martinsley and most of Witchley formed the dower lands of late Anglo-Saxon queens, and possibly Mercian queens before that; and that a royal hunting forest stretched over these two regions. He hypothesized that the division of the region took place during the Viking period in the ninth and tenth centuries and this division was incorporated into the newly formed counties in the area in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. In addition, the whole region is also remarkably free from Danish place names, despite being firmly within the sphere of influence of the Five Boroughs of Lincoln, Nottingham, Derby, Leicester and Stamford, again suggesting a shared history of some sort.

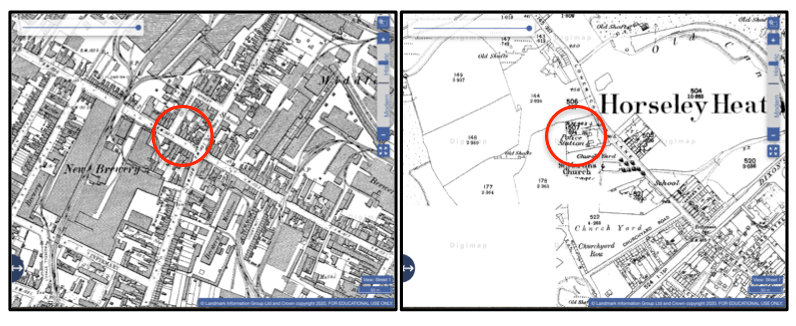

Figure 1. Rutland at Domesday (from (2))

(1 indicates Alstoe Wapentake; 2 is Martinsley Wapentake, and the remaining area is Witchly Hundred.)

Be that as it may, Phythian-Adams was unable to make much headway into the origin of the land unit that was to become Rutland prior to the Danish invasions. He suggested that it might be a small polity similar to those listed in the area of Middle Anglia in the Tribal Hidage (5), that most enigmatic of documents that I have discussed elsewhere, but was unable to say any more. He also demonstrated that there were a number of settlement names on the western county boundary that could be interpreted as watchtower / beacon or something similar, suggesting a contested boundary with whatever polity lay to the west. In addition, he noted that where the Roman Road known as Ermine Street crossed the county boundary, there were significant Roman settlements at Great Casterton and Thistleton. Roman towns on boundaries seems to have been a characteristic of the Roman east midlands, possibly to control the boundaries of different tribal areas, which again suggests that the Rutland area had an identifiable identity at that period as a sub-region of the Corieltauvi tribal area.

In this blog post we revisit this issue of the early origin of Rutland through rather a different approach – by looking at the topography and river catchments of the area, and the interaction with the eastern fenland tribal areas that have been extensively studied by Oostthuizen (6). We will conclude that in these terms, the areas that were to become Rutland and the Lincolnshire “Part” of Kesteven formed two coherent neighbouring territories with rivers that drained into the highly managed fenland boundary and the polities of the Tribal Hidage that existed there and were important in maintaining the fenland habitat. In addition, a VERY speculative reanalysis of the Tribal Hidage gives two possibilities identifications of these territories.

Topography

Figure 2. The Welland catchment

Figure 2 shows a map of the catchment of the River Welland, produced by the Welland Valley Partnership (7). On it we have superimposed

- the boundaries of the modern County of Rutland and the Lincolnshire area of Kesteven (dotted red lines)and the location of the town of Stamford (red circle);

- the tentative boundary of the Tribal Hidage region of the Spalde (around Spalding) – Oostthuizen suggests that this represented by the hundred of Elloe in the Lincolnshire part of Holland.

- The locations of the western “defensive” settlements mentioned above (green circles).

It can immediately be seen that the Martinsley and Witchly areas of Rutland, together with the area around Stamford, is effectively the area of the major part of the Upper Welland catchment and its tributaries, the Eye, the Chater and the Gwash, with the exception of a relatively narrow strip to the south of the Welland. The position of Stamford just outside Rutland in a narrow strip of Lincolnshire has frequently been noted as being anomalous, and consideration of a number of late Anglo-Saxon estate holdings suggest it was once part of the Rutland with significant estate links to the area. In topographic terms, the boundary between Rutland and Kesteven would make much more sense if it were to the east of Stamford. The defensive settlements can be seen to be at the upper end of the catchment, close to the watershed.

The area of Kesteven contains the catchment of the Glen that feeds into the Welland below Stamford. The Welland then feeds in to the fenland region of the Splade. This is of some significance. Oostthuizen shows that this area was heavily utilised for agriculture, with communal rights to use specific areas of the Fen for grazing. There are indications of the control of rivers and drainage channels in this and other fen boundary areas. This is of importance, as it implies that the Spalde would have every incentive to ensure some degree of control of the contents of the Welland and its tributaries, particularly in times of drought and flood, to ensure the productivity of their region. Thus, the two areas of Kesteven and Rutland would have been of some importance to the fenland economy of the Spalde, which points to the need for some sort of level of organization, either as separate polities, or as upland extensions of the territory of the Spalde, even if only with the status of a modern drainage authority. This in turn suggests that the origin of these two areas could arise from their topography as important catchments for the fenland economy. There is an anomaly here however – the wapentake of Alstoe is outside this catchment, with its streams flowing to the Soar and the Trent. Taken with the fact that this area was not part of the lands of the Anglo-Saxon queens, or of the Royal Forest, tends to suggest that it was not part of the original land unit.

But can we say any more about the nature and names of these two areas of Rutland and Kesteven? To that question we now turn.

The Tribal Hidage

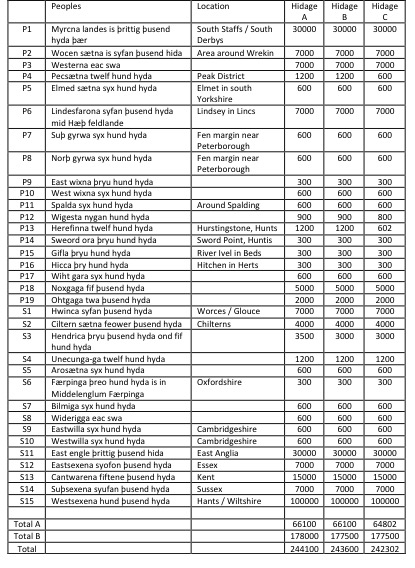

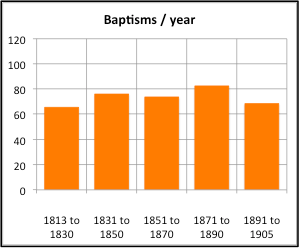

I have discussed the nature of the document known as the Tribal Hidage elsewhere – see here and here. Almost everything about this document is disputed in one way or another and great care needs to be taken in its interpretation and any conclusions that are drawn from it must be viewed with some circumspection. In its various versions, it consists of what was probably a Mercian or Northumbrian tribute list of various polities of a wide range of sizes (Table 1 reprinted from here), some of which can be identified and located, whilst the locations of others are disputed. It is arranged in two lists – a primary list and a secondary list, both, as far as can be judged proceeding a roughly clockwise direction (Figure 3 reprinted from here). Its date is as uncertain as any other aspect of the document, but for me the early date of around 620 proposed by Higham (8) seems the most logical.

Table 1 The Tribal Hidage

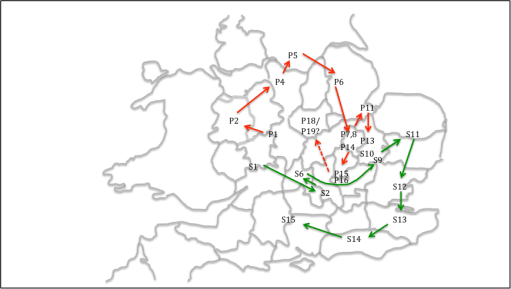

Figure 3. The order of the primary and secondary lists in the Tribal Hidage

Now in the primary list we have, at P7 and P8, the south and north Gyrwa. These can be located with some confidence in the Peterborough area, around the River Nene. The Spalde are at P11. Between The Gyrwa and the Spalde at P9 and P10 on the list, we have the East and West Wixna. These have not been located, with some writers placing them around Wisbech or the Norfolk edge of the fen to the east. However, their position in the list would suggest a location between the Gyrwa and the Spalde. As these two polities bordered each other, this is a bit tricky, but to identify them with Rutland and Kesteven is broadly consistent with the order of the list.

But there is another possibility. As mentioned above, the Tribal Hidage consists of two lists. In the Primary list, after the Hicca at P16, which can be located around Hitchen, there is the Whitgara. In the map of figure 3 I did not suggest a location for this. However, in the view of some scholars, such as Hart (5) this is an obvious reference to the Isle of Wight. In placing the unknown entities of P18 and P19 (Noxgaga and Ohtaga) in the Leicestershire / Northamptonshire area, I conveniently ignored this suggestion (on the basis that if some evidence doesn’t fit, it is best ignored – which I observe is a common practice of historians!). But if in fact the identification with the Isle of Wight is accepted, this means that the Primary list has two parts – the rotation round the north of Mercia, and then possibly three large entities in the south – Wight, Noxgaga and Ohtaga added on at the end. This would match with the suggestion of Hart who placed the latter two in the Surrey / London area. Pushing this line of reasoning a little further for the Secondary list, if this was again in two parts, we would have a rotation around the south and east of Mercia, and then a list of major subject kingdoms beginning with East Anglia running around the east and south of England. This in turn opens up the possibility of not having to consider placing S7 to S10 in the South Midlands in order to proceed from S6 (Faerpingas) in Oxfordshire to East Anglia (S11) in a reasonably logical way, but they could be allowed to be in the East Midlands where there is something of a hole on the map. Of particular interest are S9 and S10 – the East Willa and the West Willa. Hart places these in southern Cambridgeshire and argues that the name Willa is cognate with the name of the Well stream, a major waterway in the area. An identical argument could apply for polities next to the River Welland ie Rutland and Kesteven. However , the chain of assumptions is a long one, and this identification should be regarded as very speculative.

Concluding remarks

A consideration of the topography of the Welland Catchment, suggest that this may have been what defined the boundaries of what were to become Rutland and Kesteven. In the early Anglo-Saxon era, both these polities would have been important to the economy and agriculture of the Fenland boundary, and especially the region of the Spalde. In addition, it seems possible that we could identify Rutland and Kesteven with the Tribal Hidage polities of either the East and West Wixna, or the East and West Willa. Of these, the first two fit most naturally into the order of the Tribal Hidage, whilst the last two are most linguistically likely. But neither may be correct!

References

- Thorn F (1980) “Rutland Domesday*”, Domesday Book 29, series editor John Morris

- Prince Yuri Galitzine (1986) “Domesday Book in Rutland – the Dramatis Personae”, Rutland Record Society, ISBN 0907464 05 X

- Phythian-Adams C (1977) “Rutland Reconsidered’ in Ann Dornier, ed., “Mercian Studies”, Leicester, 63-84

- Phythian-Adams C (1980) “The Emergence of Rutland and the Making of the Realm“, Rutland Record 1, 5-12

- Hart C (1971) “The Tribal Hidage”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fifth Series, 21 (1971), 133-157

- Oosthuizen S (2017) “The Anglo-Saxon Fenland”, Windgather Press

- Welland Valley Partnership (2013) “Enhancing the River Welland“,

- Higham N (1995) “An English Empire – Bede and the early Anglo Saxon kings”, Manchester University Press.