The altar at St. Michael-on-Greenhill Lichfield, with Pentecost frontal

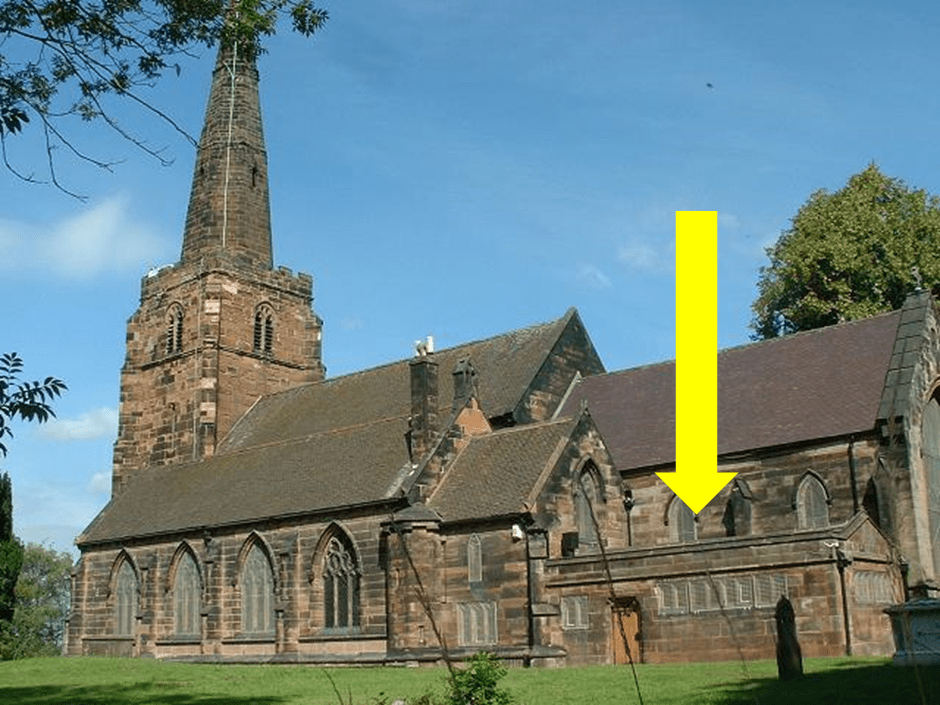

It hasn’t been my habit to publish my sermon output on this site for two reasons – firstly, sermons always have a context – a time, a place, a certain set of hearers etc. and, my sermons at least, would lose much of their force outside this context. And secondly, I hardly ever write down my sermons, so preparing them for the web would be extra effort! But the sermon below is a significant one for me – the last sermon I preached at St. Michael-on-Greenhill in Lichfield on Pentecost 2023, and the last time I celebrated the Eucharist, having ministered there as a non-stipendiary minister for 25 years – and it seemed appropriate to record it. But it needs to be said that the text below is only a rough approximation to what was actually said, written down after the event.

As ever when working on sermons it is a learning experience, and from my perspective there are two insights that seem to me important (that do not particularly feature in the sermon). The first is the significance of the presence of Mary the mother of Jesus at the events described in Acts 2, and the striking parallel between the coming of the spirit upon her at the Annunciation and the Pentecost events. These were in both cases a creative act – the incarnation and the creation of the church, and Mary was the only one present who had experience the overshadowing of the Spirit before the Pentecost event. Of course this has been blindingly obvious to many in the past, not least to the entire catholic church (and see for example here for a recent non-catholic discussion) but its importance has only just dawned on me. The second point concerns the coming together of all the members of the early church between the Ascension and Pentecost. It seems to me that this could have implications for the beginning of the various gospel traditions. This period offered a chance to for all those present to tell and to hear all of the different disciples’ experiences of what Jesus said and did – stories that were eventually used by the different gospel writers in their own distinctive and idiosyncratic ways. The sources of the Petrine, Johanine and even the Q tradition, can perhaps be located in the stories the early church told each other in this period.

The sermon follows below the rather striking and inspirational depiction of Pentecost by Jean Restout below, which puts the figure of Mary in the centre of the event. The sermon will be found to be somewhat less striking and inspirational.

Jean Restout (1692–1768) Pentecost

Acts 2.1-21 John 20.19-23

When the day of Pentecost came…..

Pentecost was, and indeed still is, one of the major festivals of the Jewish liturgical calendar, 50 days after Passover. It is both a harvest festival, and the annual remembrance of the giving of the law to Moses on Mount Sinai. Jerusalem would have been busy with pilgrims from Judea and Galilee and from the whole Jewish diaspora around the Mediterranean and the Middle East. The followers of Jesus, were indoors, perhaps still keeping a low profile, as at least for some of them, it might well be dangerous for them to be seen in public following the events of 50 days before. Luke, the writer of Acts, tells us they were all together in one place. As he has already told us in the previous chapter that there were around 120 followers of Jesus at that time, this implies somewhere rather large – perhaps with an internal courtyard, or that we shouldn’t put to much weight on the word “all”. At any rate it was a diverse group that gathered there – the eleven disciples and Matthias who had replaced Judas; the women who had supported Jesus financially during his ministry, including Mary Magdalene; perhaps those disciples who lived in the vicinity of Jerusalem – Mary, Marth and Lazarus, and Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus; and also members of Jesus’s family – certainly his mother Mary was there. And as they gathered together in prayer and worship, although they weren’t as terrified as they had been following Jesus’s death, they were perhaps puzzled, not knowing what to expect. In the finality of their last meeting with the risen Jesus, he had told them to wait in Jerusalem, and he would send the Holy Spirit to be with them. What were they expecting? They would know what the scriptures said about the Holy Spirit of course. God sent his Spirit powerfully on judges, kings and prophets to give them the ability to perform the tasks he had given them, often in difficult and dangerous circumstances. But they would also know of what the first few verses of Genesis says about the Holy Spirit.

“The earth was a formless void, and the Spirit of God hovered over the face of the waters”

The Spirit hovered over the formless primeval chaos. The metaphor here is picked up in the book of Deuteronomy where the same words are used to describe the mother eagle spreading her wings over her brood and lifting them gently in her talons, and indeed the verse can also be translated as the Spirit of God brooded over the face of the waters. The waters, the deep, would have been regarded as a place of terror, the deep places of the Leviathan. And the Spirit hovered, brooded over the primeval chaos and the terrors of the deep, to bring creation in to being, to give it birth and to nurture it. This same metaphor occurs throughout scripture. The psalmist frequently cries

“Hide me under the shadow of your wings.”

The creative, nurturing, protective Spirit. The psalmist also speaks of the ever-present Spirit

“Where can I go from your spirit? Or where can I flee from your presence? If I ascend to heaven, you are there; if I make my bed in Sheol, you are there. “

But as well as these verses from Scripture describing the action if the Spirit, the disciples who gathered that day would have added their own personal knowledge. Some would have remembered the words of the Baptist.

‘I baptize you with water for repentance, but one who is more powerful than I is coming after me; I am not worthy to carry his sandals. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire.

Some will have remembered the Spirt, like a dove, descending on Jesus at his baptism. There were also the words of Jesus himself, describing the Spirt as a bringer of comfort and peace, equipping them for what was to follow, and being with them always. Then perhaps they would have listened to the one amongst them who had actually experienced the coming of the Spirit. Perhaps it was at this time that Mary would have told the group of the coming of the angel, her overshadowing by the Spirit, and her submission to God’s will,

“Be it unto me according to your word.”

And too, she might have told of the prophecy of Simeon that a sword would pierce her own soul, and the dreadful fulfillment of that prophecy.

But, based on all of these things, just what were they expecting? Almost certainly not what actually happened. Suddenly the house was filled with light and noise, a light that seemed to focus down on each one of them, bringing to each a realization of the presence of God. Much scholarly ink has been spilled on the significance of the wind and flame, but I doubt at that time the followers of Jesus stopped to think “This is rather like what the Baptist said would happen” or “The wind and the flame are symbols of Pentecost, of the giving of the law at Sinai”. No, for them, it was an objective, overwhelming experience. For Peter maybe the final assurance of his forgiveness for his betrayal; and his commission as leader of the group; for John, the disciple whom Jesus loved, the renewal of intimacy with his closest friend; for Mary Magdalene, told by Jesus not to cling to him, the all encircling presence of her Lord and teacher; for Joseph and Nicodemus, the burning intensity of the life in Jesus, whose cold body they had laid in the tomb; for Jesus’ family, the return of their beloved big brother; for Mary, the inexpressible joy at the presence of the spirit of her son, the erasure of the pain of the piercing sword. All their experiences with Jesus found their fulfillment at this point, and from there something new flowed. But for all of them, and experience of the overwhelming Spirit of Jesus, that forced them out of the house into the city, praising God and then, through a miracle of interpretation being understood by all, now matter where they came from.

Finally, through the chaos and the cacophony, Peter pulled himself together, perhaps stung by the accusations of drunkenness, and interpreted the events in the best way he could – going back to the prophecy of Joel that, on the day of the Lord, the spirit would be given to God’s people, the old would dream dreams, and the young would see visions.

It is often said that Pentecost is the church’s birthday – and in the years that followed, the Holy Spirit hovered, brooded over the nascent church, nurturing it through its growing pains – and they were indeed pains, that pierced as sharply as any sword, as the followers of Jesus came to the realization that the life of that body couldn’t be contained within the confines of Judaism, but was for the whole world, and they had to let go of much that was precious to them to allow this to happen.

So, what are our expectations this morning? Have we come here, just looking for a quiet break from the affairs of the week; or thinking that because its Pentecost, there will be some good hymns to sing; or perhaps to have a glass of wine at the end of the service to celebrate finally getting rid of the preacher after 25 years? If so, perhaps we need to raise our expectations somewhat.

Today, as was the case almost 2000 years ago, the Spirit still broods over the church, overshadowing us, offering us forgiveness and reconciliation, renewal of faith that has gone cold, stability in the chaos that surrounds us and hope for the future, the calming of our own terrors, offering new life and the outpouring of God’s love; waiting for us to turn and accept that invitation “Lord be to me according to your will”.

The Spirit today hovers over Greenhill, calling on those to us who belong to the church of the Archangel, calling for the old to dream dreams and the young to see visions. I suspect looking around there will be a preponderance of dreams. But what are our dreams for the future of the church in this place? How can we work with the brooding, nurturing Spirit to bring those dreams to reality?

And finally, as 2000 years ago, the Spirit sends us out – perhaps not to the market square (where in any case we would have trouble fining space in the middle of the Bower fun fair) but to go about our lives serving and meeting the needs of those around us, wherever that might be. And he promises to never leave us. With this in mind we return to the words of the psalmist.

Where can I go from your spirit? Or where can I flee from your presence? If I ascend to heaven, you are there; if I make my bed in Sheol, you are there. If I take the wings of the morning and settle at the farthest limits of the sea, even there your hand shall lead me, and your right hand shall hold me fast. If I say, ‘Surely the darkness shall cover me, and the light around me become night’,

even the darkness is not dark to you; the night is as bright as the day, for darkness is as light to you.

Or in the old words, which are still the ones that come immediately to my mind.

Whither shall I go from thy spirit? or whither shall I flee from thy presence?