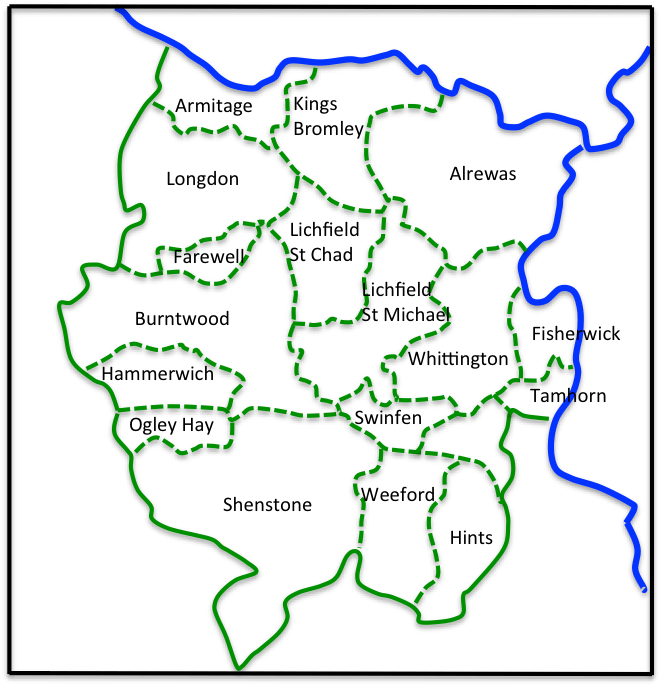

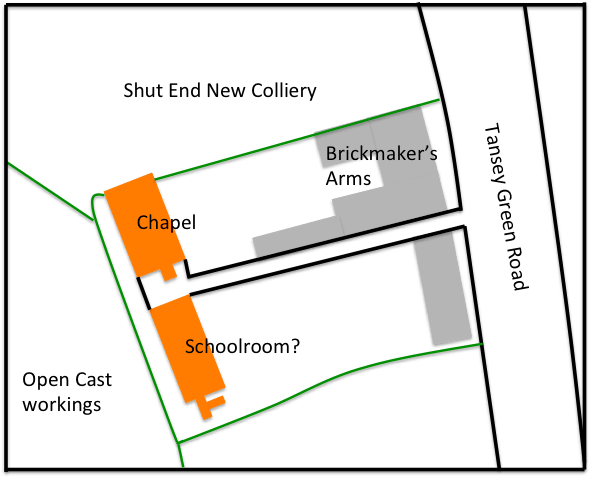

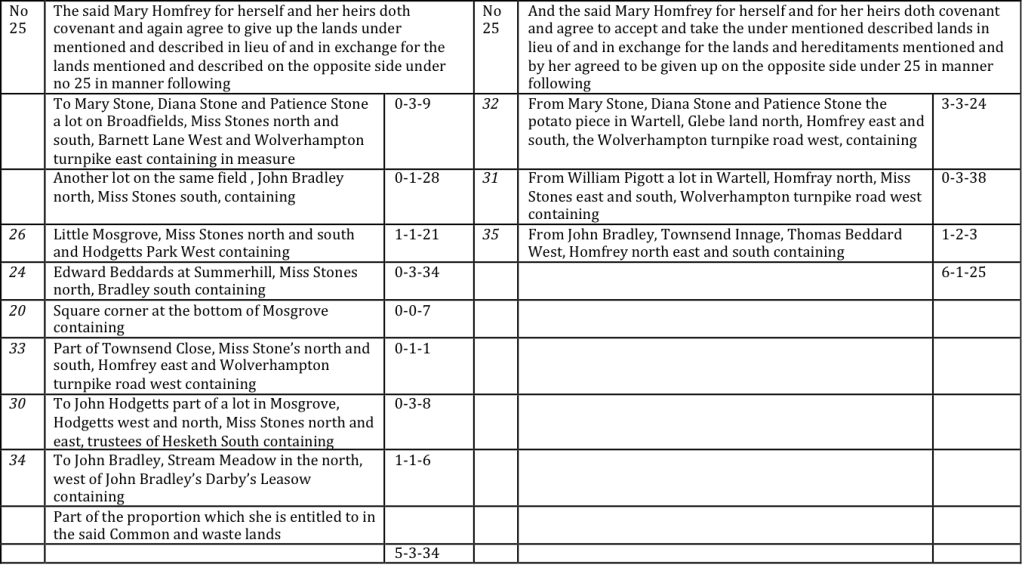

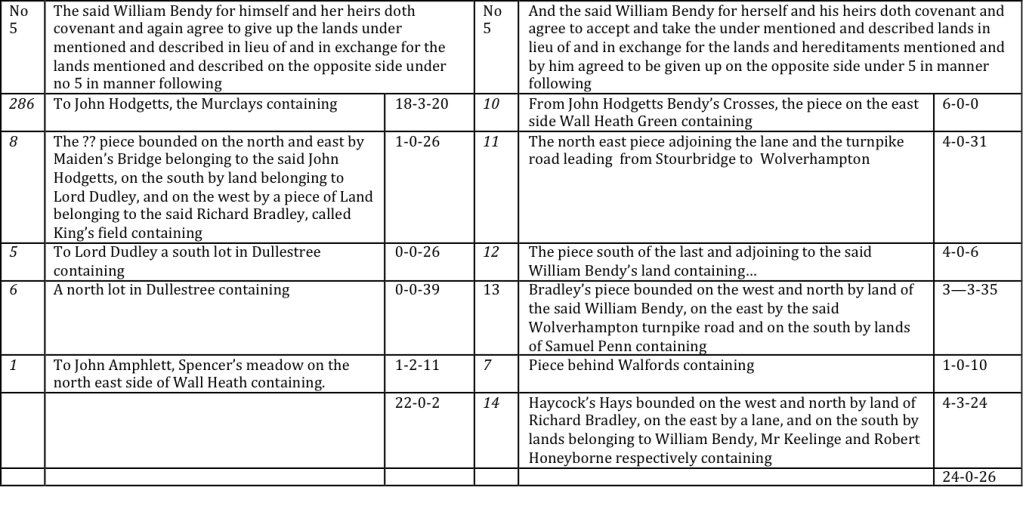

Shut End and Corbyn’s Hall

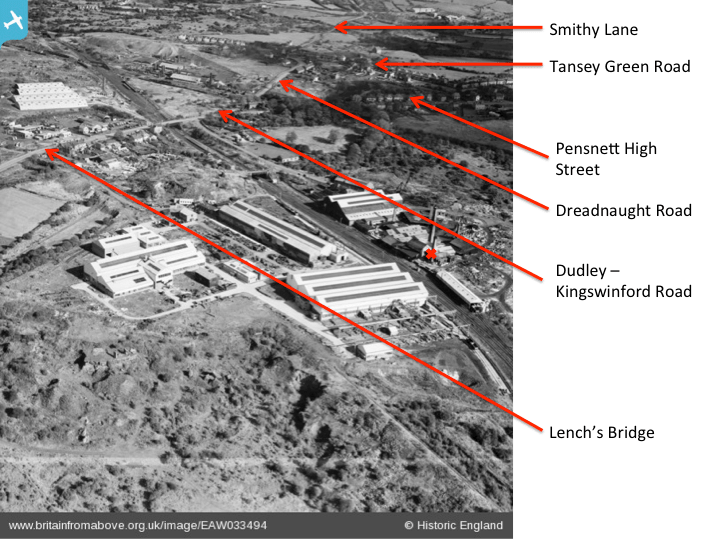

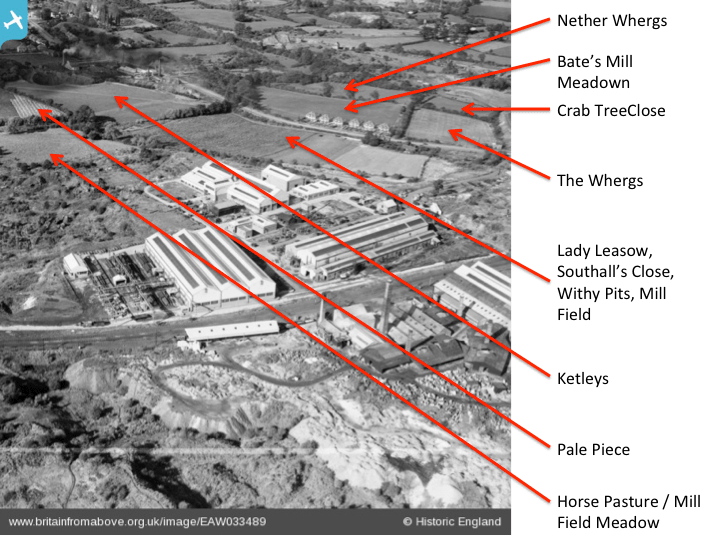

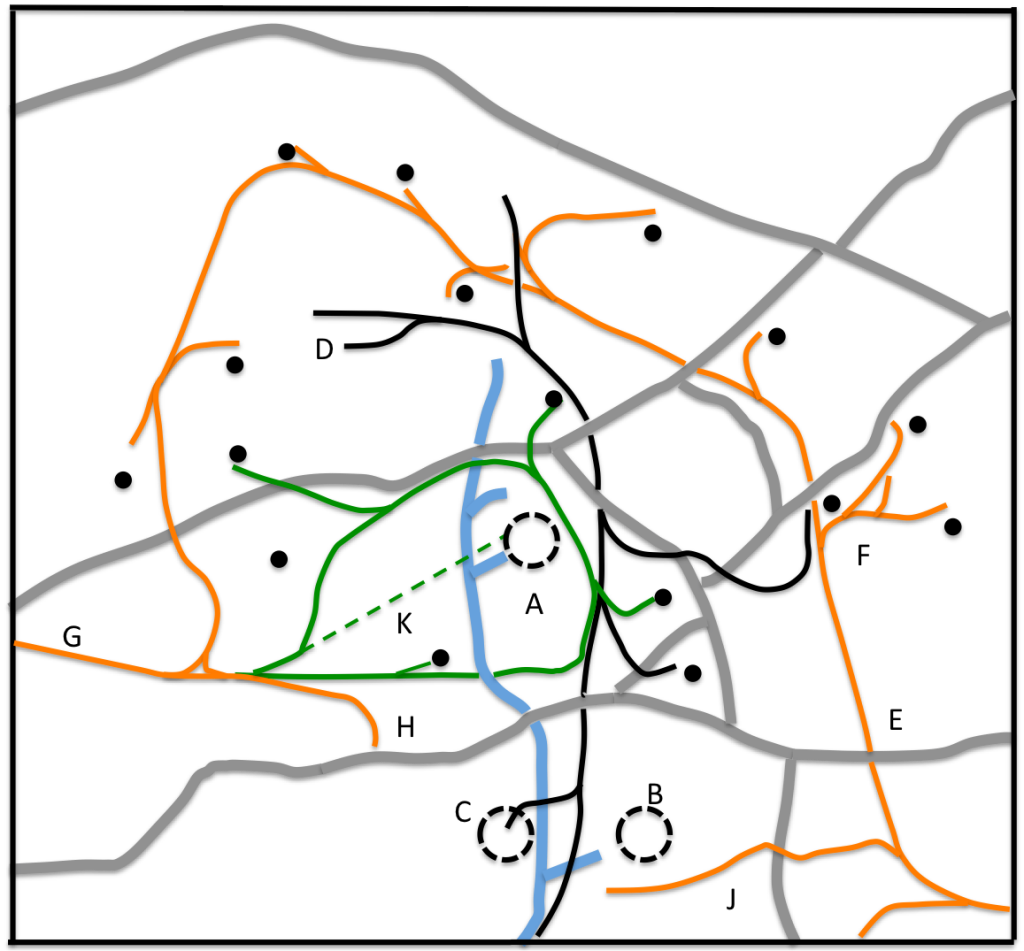

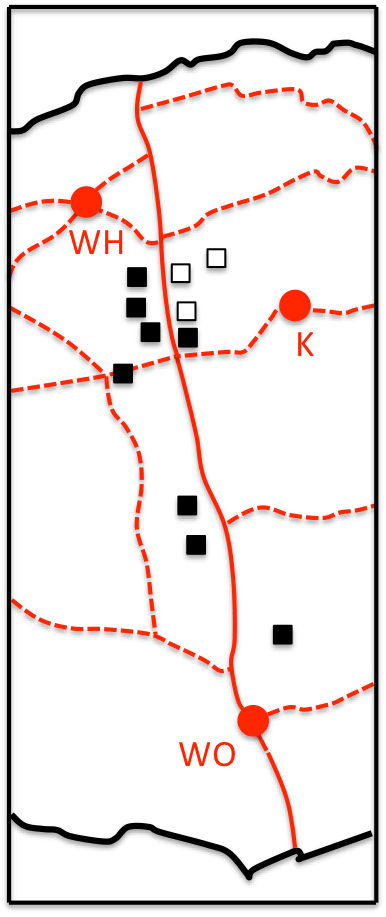

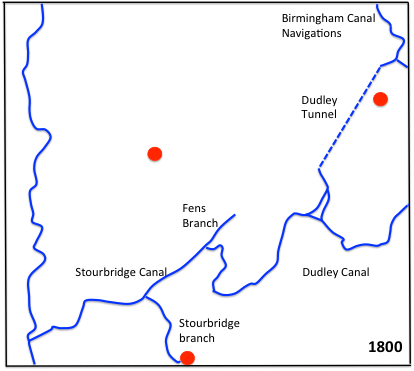

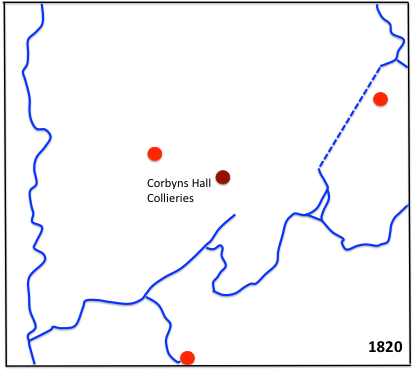

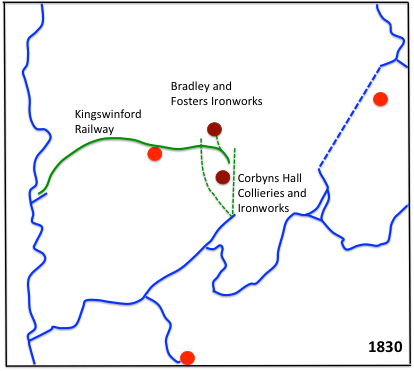

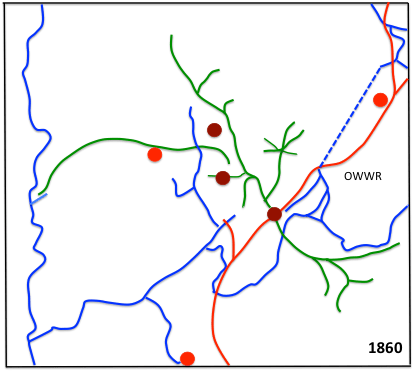

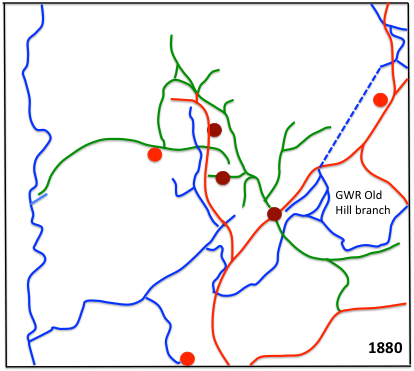

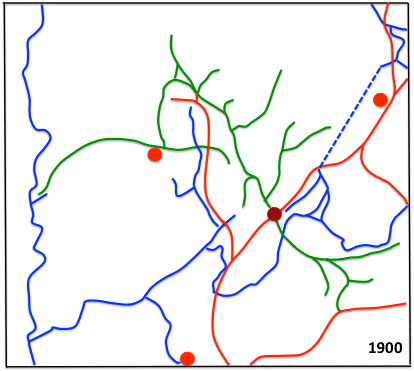

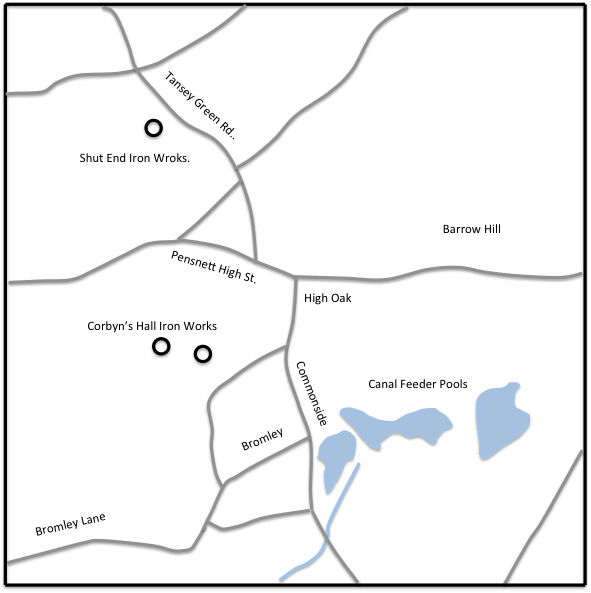

In an earlier post, I discussed the railway system around the Shut End and Corbyn’s Hall Ironworks and Colliery complexes in Pensnett in the late 19thcentury. One reader of that post pointed me in the direction of the Coal Authority web site, which contains huge amount of information about disused coalmines across the country, including of course the Shut End and Corbyn’s Hall area. It really is a fascinating site, and I would encourage readers to have a look at it. What I want to do in this post is to use some of the information presented there to give more details of the mining operations that I briefly discussed in Kingswinford Manor and Parish (KMAP) and in the blog post just mentioned. Figure 1 shows the area that I will concentrate on, which is centred on the High Oak in Pensnett where Commonside meets Pensnett High Street. The figure shows the major roads in the area; the canal feeder pools, which are such a major feature of the local geography; and the locations of the Ironworks at Shut End and Corbyn’s Hall.

Figure 1 The study area

Topography and Geology

Figure 2 shows the topography of the study area, with the elevation profiles taken from Google Earth. It can be seen that it falls quite steeply from east to west from around 150 a.s.l. in the east to around 90m a.s.l. in the west. This will be seen to be of importance when considering the depths of coal seams and mines below.

Figure 2 Topography of the study area from Google Earth

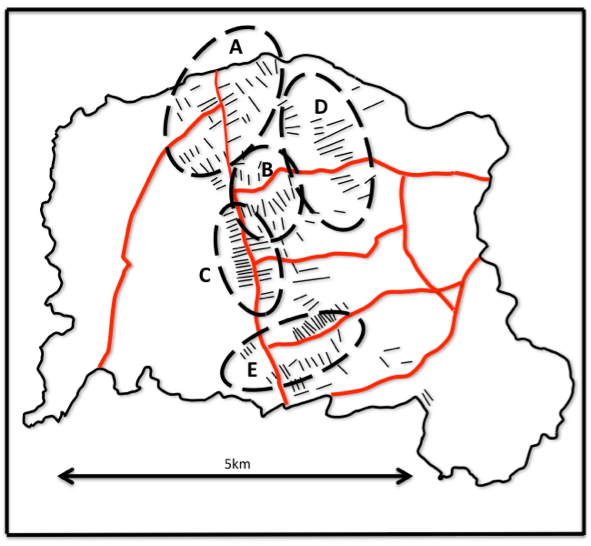

Details of the geology of the area can be obtained from the Edina Digimap web site. Figure 3 shows the underlying bedrock geology of the area. This has been very much simplified from the Digimap version to show only the major features. There are four main types of underlying geology – sandstone to the west and in outcrops across the area; an igneous outcrop in the Barrow Hill area; large areas of the Etruria formation of sandstone / mudstone, with some areas of Pennine Coal measures formation of sandstone / mudstone / siltstone. The latter two are the principal coal bearing strata. The major faults are also shown. The fault to the west is actually the edge of the South Staffordshire coalfield. There can be seen to be a number of faults in the area, which cause quite complex underground coal seam patterns. This will be discussed further below.

Whilst the figure shows the underlying geology, close to the surface the nature of the land changes completely, and the Digimap website describes it as “artificial ground” – a somewhat euphemistic description of the fact that the whole area is largely built on waste and colliery spoil.

Figure 3 Geology of the study area from Edina Digimap

The Coal Authority web site

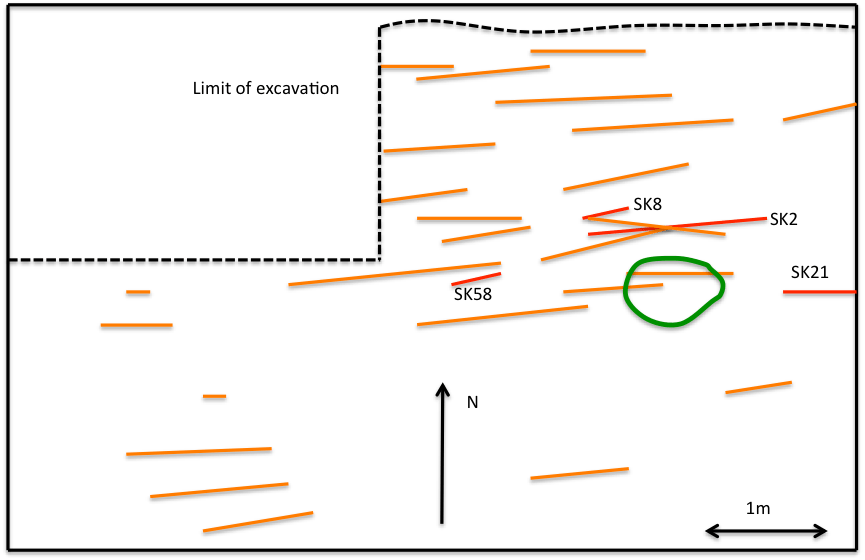

We turn now to the information provided on the Coal Authority web site. Coal has been mined over the entire region around our study area for many hundreds of years, firstly exploiting surface outcrops of coal, and then digging deeper and deeper mines to bring the buried coal to the surface. Most of the main surface outcrops of coal in the region were in the area south and east of Brierley Hill, which unsurprisingly was the first part of the ancient parish of Kingswinford to undergo industrialization. In our particular study area there were however a few outcrops (figure 4) – at Brockmoor in the south and in the Coopers Bank / Old Park areas in the north.

Figure 4 Surface outcrops of coal from Coal Authority web site

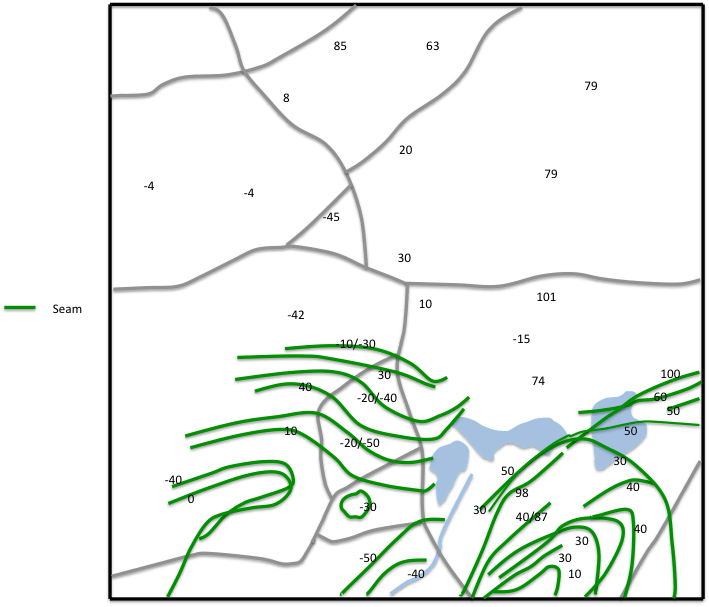

Figure 5 shows the seams of buried coal, where there is sufficient information for the contours to be mapped, and spot depths for seams at other points. The heights of the seams are all given in metres a.s.l. This figure needs to be considered in the light of the topographical information in figure 2 to enable the depth of the seams below ground level to be appreciated. The shallowest deposits are to the east of the area where the seams can be as little as 30m below the ground. In the west of the area, the seams are much further below ground level – up to 150m. The deepest mines in the region were ultimately to be those at Baggeridge to the north of the study region, where the deposits were 350m below sea level.

Figure 5 Coal seams and depths from Coal Authority web site

Looking at the distribution of coal from another direction, figure 6 shows a section through the study area from a drawing by William Matthews in a paper he wrote in 1860. Matthews was the proprietor of Corbyn’s Hall Iron Works at the time and a little more issued about him in KMAP. The approximate location of the section is given on figure 3. The line as specified by Matthews is a direct line from Dudley Castle to “Kingswinford” although where in Kingswinford is not spelt out and it is not possible to identify the precise location of the line. That being said the location of the igneous outcrop at Barrow Hill can be seen and the faulted and fractured nature of the coalfield is apparent. The need for deep pits to extract the bottom seams of coal is also clear.

Figure 6. Section through the study area (redrawn form Matthews , 1860)

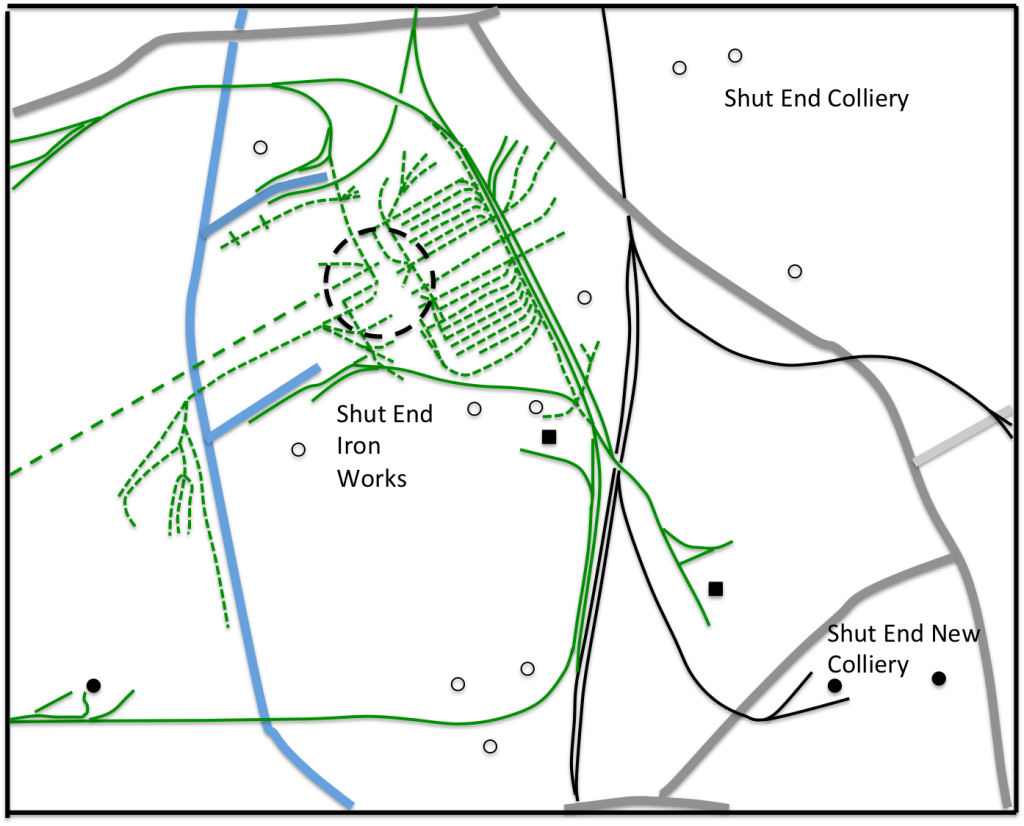

Figure 7 shows the “mine openings” as defined on the coal authority site. These mines were not of course all operating at the same time, so the map gives no temporal information. But the huge number of openings is instructive (and the density here is by no means as high as in the older Black Country mining areas of Bilston and Wednesbury). The site gives name information for many of these, which to some degree is indicative of ownership. The five main groupings are indicated on the map of Figure 7 as follows.

- The Shut End group, originally owned and operated by James Foster in the 1830s as part of the Shut End Iron Works complex, and later by the Shut End Colliery Ltd.

- The Tiled House / Corbyn’s Hall group, developed by Ben Gibbons and his associates in the 1830s to 1850s, and which provided coal for the Corbyn’s Hall Iron Works.

- The Himley Group of the Estate of the Earl of Dudley. It can be seen that this was to the east of Commonside, which was, in the main, the boundary of the Pensnett Chase Enclosure Award of 1784. A clause in the act reserved all the underground mineral rights to the Earl of Dudley and his successors, even where the land itself was allocated to others. The estate exploited these rights to the full over the next century and a half.

- A group in the Old Park area, which had been mined to varying degrees for several centuries by the Earls of Dudley.

- A group of mines around the Wallows / Woodside, which were probably also part of the Dudley estate.

Figure 7. “Mine openings” from Coal Authority web site

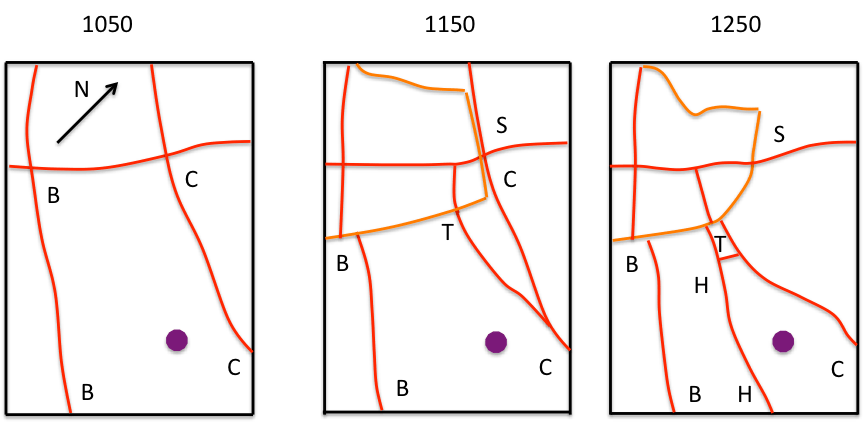

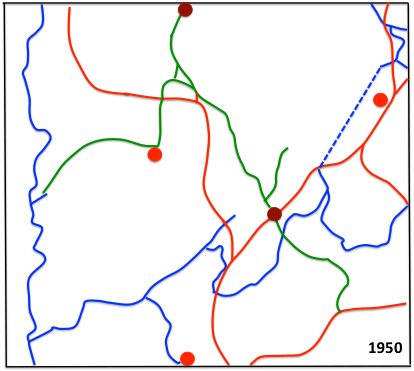

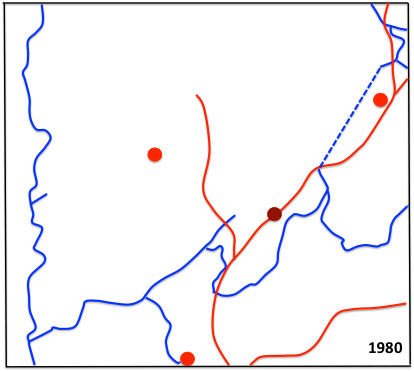

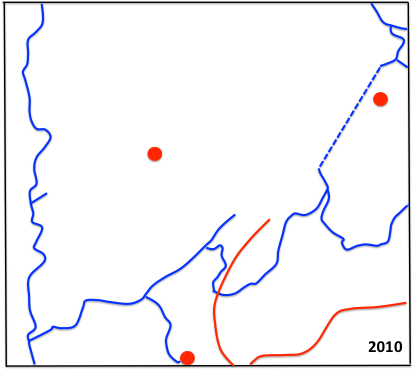

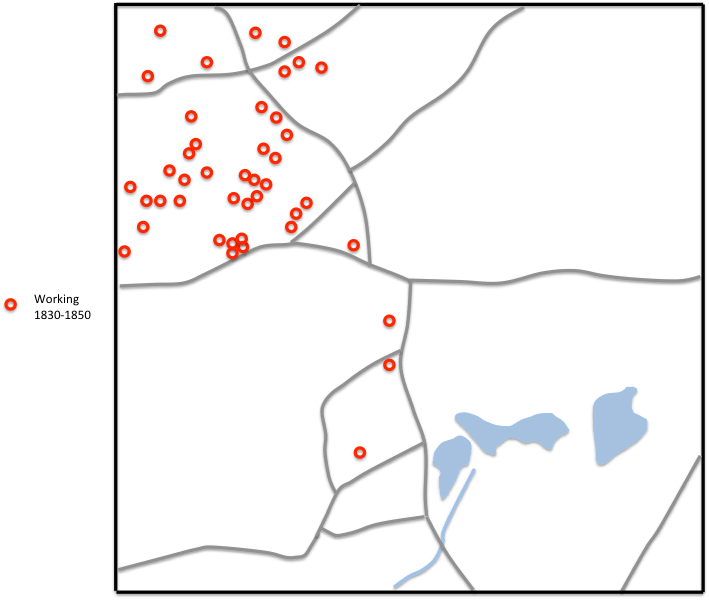

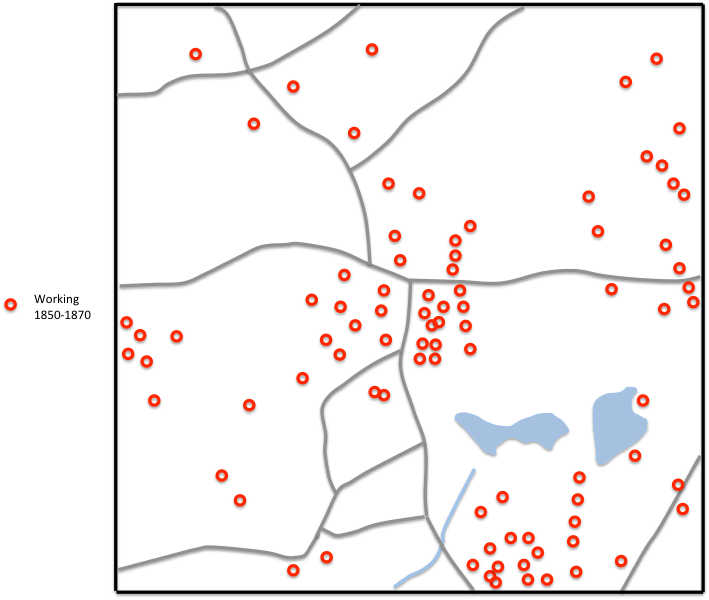

If the “mine opening” category on the Coal Authority site does not give temporal information, the “mine working” category does. For each mine that is included, it gives a year when it was working. The precise definition of this year is not clear to me i.e. was it the first year of operation; the last year; or something in between? But at least it gives an indication of when mines were in operation. I have presented this data in figures 8, 9 and 10 in twenty-year time slices – 1830-1850, 1850 to 1870 and 1870 to 1890. The former corresponds to some degree to that given on the 1840 Fowler map of Kingswinford, and the latter to the period I considered in my earlier post where I discussed the railways of the area. A comparison of the maps is instructive. Between 1830 and 1850 the highest concentration of mines is in the Shut End area, where the Iron Works was in operation, with limited mines around the Corbyn’s Hall area, presumably feeding the Iron Works there. Between 1850 and 1870 the mines close to the Shut End Iron Works had clearly all been worked out, and supplies were brought in from somewhat further afield by rail – a process I discussed in the earlier post. In this period there was much more activity around Corbyn’s Hall and the High Oak area of Pensnett, and mines were operating in the Wallows and Old Park areas. It can thus be seen that the exploitation of the coal reserves by the Earl of Dudley’s estate was well underway in this period. In the 1870 to 1890 time slice, the situation has changed again with the most heavily exploited areas being in the Fens and Barrow Hill regions. Many of the mines in this area were in the residential areas of upper Pensnett. A cluster of them was around Pensnett church and vicarage, and no doubt contributed to the long term subsidence problems of structural damage to the church. Comparing this information with that given in KMAP for the distribution of the coal pits on the 1840 Fowler Map and the 1883 Ordnance Survey map, shows that these two sources show far fewer pits than the Coal Authority map. This might be of course simply because they show the situation at a particular time rather than in a twenty year time slice, but it does give some idea of both the short lived nature of many of the mines, and the uncertainties in handling data from different sources.

Figure 8. “Mines working” between 1830 and 1850 from the Coal Authority web site

Figure 9. “Mines working” between 1850 and 1870 from the Coal Authority web site

Figure 10. “Mines working” between 1870 and 1890 from the Coal Authority web site

Final thoughts

Two final thoughts come to mind, in connection with items I have already posted. Firstly in Kingswinford Manor and Parish, when considering the spread of mining through the parish of Kingswinford I rather simplistically suggested that, during the nineteenth century, there was a gradual spread from the old mining areas in the Brierley Hill area in the south of the parish, northwards towards Pensnett and Shut End. The situation described above shows that it was rather more complex than that, with an early exploitation of the coal reserves around Shut End, and to a lesser extent Corbyn’s Hall, followed by a gradual “filling in” with mines of the areas between Brierley Hill and Brockmoor and Shut End over the next half century.

Secondly in my earlier post on the Railways of the area, I put forward a model of how Ironworks / Colliery complexes developed in the area – firstly with ironworks and coalmines being in close proximity; then as the coal reserves became exhausted, with railway systems being developed to bring coal from mines somewhat further away but still in the locality, and finally with coal being brought from considerable distances. Figures 8 to 10 above tend to confirm this model in the Shut End area in particular, with the early development and later decline of mines close to the ironworks there, but there is also evidence of the same process around Corbyn’s Hall.

Without a doubt the Coal Authority web site has a huge amount of data of interest to industrial historians, and I am very grateful that I was told about it. In this post I feel I have only scratched the surface of this material – so I may well return to it in future.