An address / sermon delivered by me at All Saints Oakham on March 10th 2024, at a Choral Evensong during the Queen Edith Festival. A video recording of the service can be found on the Oakham Team Ministry Facebook page.

By way of introduction, you will see that in Worship for the Week I am referred to as a professor, which seems to give this address some level of academic respectability. And while that appellation is true enough, my actual title is Professor of Environmental Fluid Mechanics, and I have spent my career teaching civil engineering students. In terms of expertise on Queen Edith, I fear, ladies and gentlemen, you have an imposter in your midst. But let’s see where we get to.

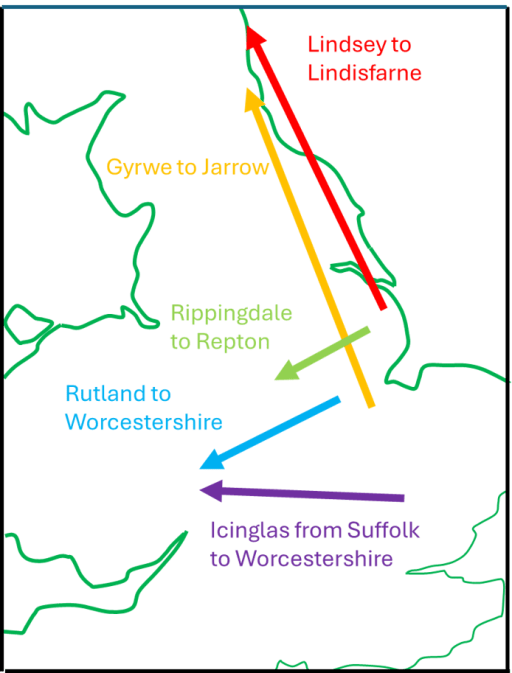

Edith of Wessex was born sometime around 1024 or 1025, so saying we are celebrating the 1000th anniversary of her birth is a bit of a guess, but not a bad one. Her father was one of the most powerful men in the country at that time – the Saxon Earl Godwin. Her mother was Danish, Gytha, a relative of Cnut, the then king of England, Norway and Denmark. England was that time was an ethnically and linguistically very diverse society with the undoubted tensions that resulted. Edith’s brothers and sisters mostly had Danish names, and she too most probably was given a Danish name that was to be changed when she married. I think it likely her mother tongue was Danish. She was brought up and educated at Wilton Abbey near Salisbury, and came to speak Danish, English, Latin and Irish fluently. She also was very capable in weaving and embroidery and, we are told, in a work she commissioned, accomplished in grammar, rhetoric, arithmetic and astronomy.

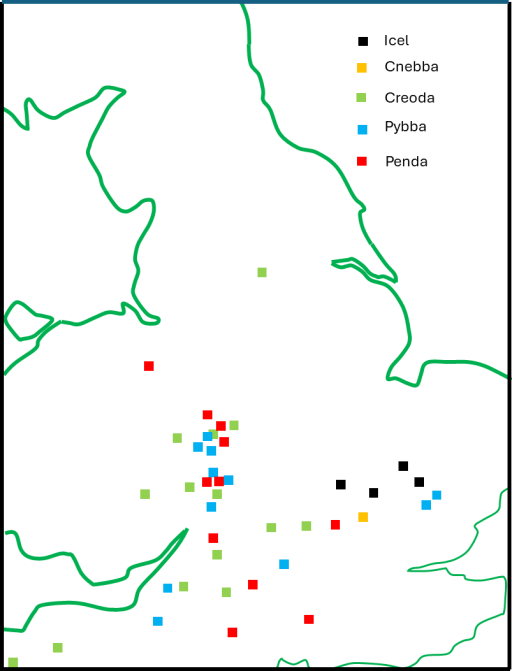

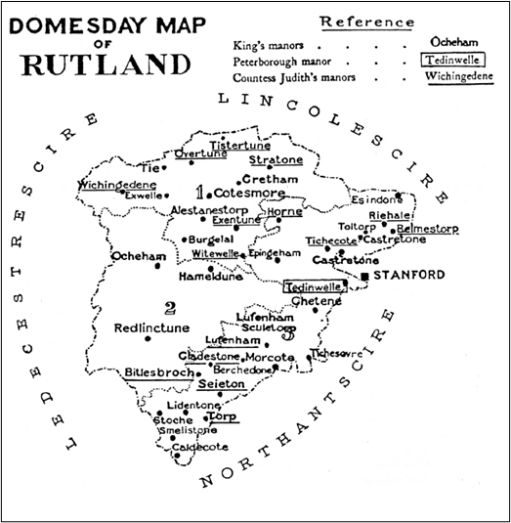

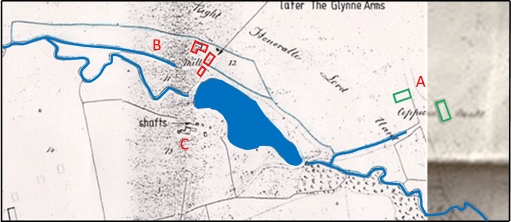

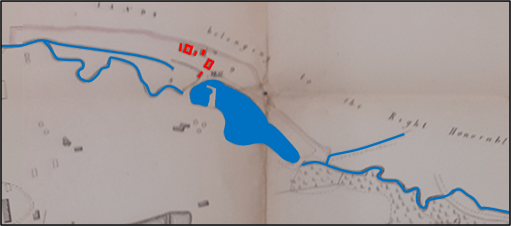

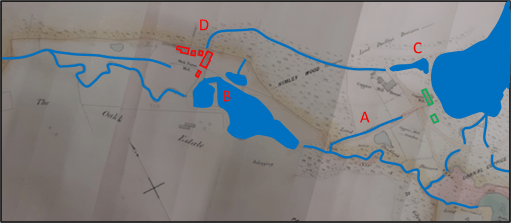

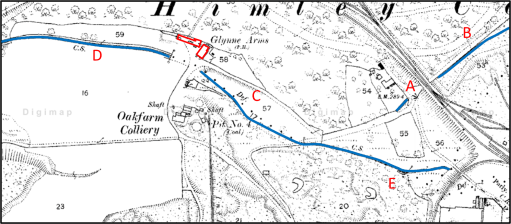

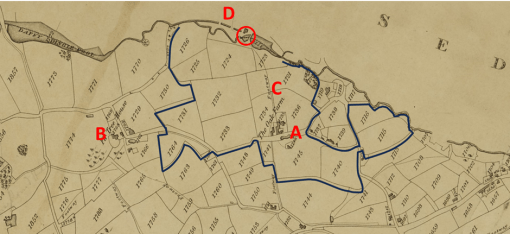

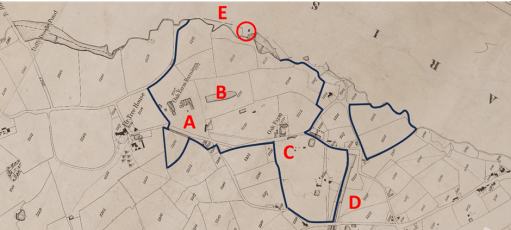

After the death of Canute and his son Harthacnut, the Anglo-Saxon dynasty that their ancestors had forced into exile was re-established in 1043 with Edward, ultimately to be known as Edward the Confessor, taking the throne. Edith was married to Edward in 1045 and, unusually for the time consecrated as well crowned as queen. For the first few years of her marriage, she would have lived in the shadow of Edward’s mother, the dowager queen, Emma of Normandy, the wife of Edward’s father Aethelred, and then the wife of Canute, a redoubtable and quite ruthless lady. I would imagine there were mother-in-law issues. The marriage was childless, which no doubt caused both personal and political tensions. In 1051, Godwin came close to armed rebellion, and he and his family were forced into exile, with the loss of his titles and his lands. Edith also fell out of favour and was consigned to a nunnery, perhaps as a prelude to a planned divorce because of her childlessness. Just over a year later, the situation was reversed, and Edward, faced with the threat of an armed conflict that he could not win, was obliged to reinstate Godwin to his former titles and lordships, and over the next 13 years, the Godwins became very powerful, holding most of the large earldoms in England. Edith too was released from the convent and reinstated as Queen. She was to become a close confidante and advisor to her husband, a de facto if not de jure member of the Witan, his body of counselors. We are told she took care to ensure that his royal dignity was appropriately displayed in his dress and his presentation. She acquired large estates and became a very wealthy woman – including most of Rutland, which were the dower lands of the later Mercian and Anglo-Saxon queens. That wealth was also used in generous benefactions to the church, particularly in Winchester and Abingdon.

The question of succession was ever apparent. Edward brought back to his court other members of the Anglo-Saxon dynasty who had been in exile following the Danish takeover, and Edith took on parental responsibilities for the young boy Edgar, named the Aetheling as being eligible for the throne, and his sister Margaret, who Edith arranged to be educated at Wilton. The latter was to marry Malcolm Canmore, King of Scotland in around 1070, for whom, allegedly, Birnam Wood to Dunsinane didst come, and it was through their descendant’s marriage into the Norman royal line that the ruling family of England again came to be connected to Cerdic, the sixth century founder of the Wessex dynasty. In retrospect, Edith’s care for the child Margaret was thus to be of major long-term significance.

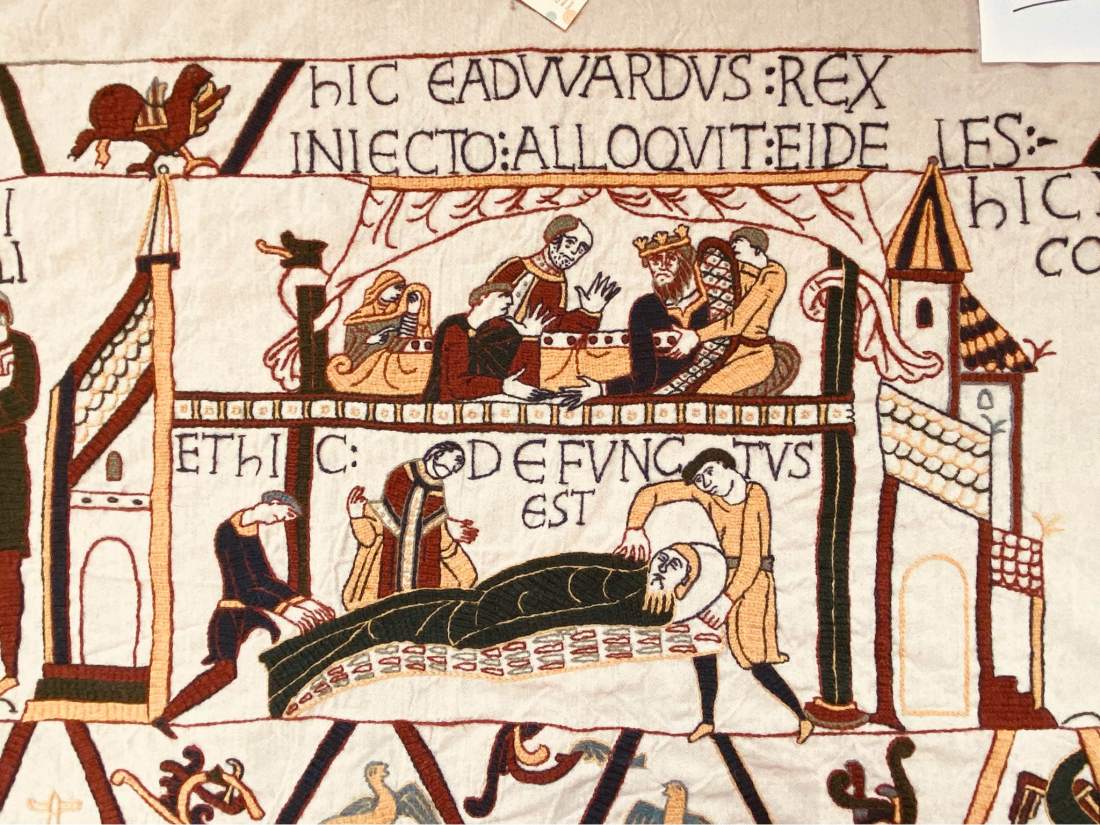

Over the latter part of his reign, Edward became increasingly occupied by the building of the Abbey Church at Westminster, which was consecrated in December 1065, just before his death and burial there in January 1066. The succession question then became critical. The claims of Edgar the Aetheling were swept aside, and the throne was taken by Harold Godwinson, Edith’s elder brother. This was disputed by both the King of Norway and, of course William of Normandy. By October that year, Edith had lost not just a husband, but her brother Tostig at the battle of Stamford Bridge, where he fought against Harold on the side of the Norwegian king, and three other brothers at the battle of Hastings. Edith submitted to William at Winchester and was allowed to keep her estates, the only surviving member of the Anglo-Saxon royal family to remain in England. In the years before her death in 1075, she continued to be a benefactor of various churches, and if some historians are correct, was instrumental in the design and production of the Bayeux Tapestry, or more properly the Bayeux embroidery. She also commissioned a book on the life of her husband and continued to manage his reputation after his death – and her actions were in large part responsible for his cannonisation several hundred years later. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of 1075, we read

Edith the Lady died seven nights before Christmas in Winchester, she was King Edward’s wife and King William had her brought to Westminster with great honour and laid her near King Edward, her lord.

But what can we say about Edith as a person? Well, it depends upon what you read – the sources that we have can best be described as propaganda for various parties. They were either produced under the direction of Edith herself, or by those who saw her as a traitor. They describe her variously as moderate and wise, or hard and interfering. She is also alleged to have been involved in a number of church and court intrigues and was accused of rapaciously appropriating religious relics from churches around the kingdom and giving them to those she favoured. and of facilitating the murder of a Northumbrian noble, on behalf of her brother Tostig, the then Earl of Northumbria. It is simply not possible to say whether these descriptions or the allegations were true, and most probably have the same level of historical reliability as the Marriott Edgar poem that sees, at the conclusion of the Battle of Hastings

King Harold so stately and grand, Sitting there with an eyeful of arrow, On his horse, with his hawk in his hand.

But, with regards to Edith, taking all things together, it is probably fair to say that she was no saint. The words of Dylan Thomas through the Rev Eli Jenkins of Llareggub seem applicable.

We are not wholly bad, or good, who live our lives under Milk Wood.

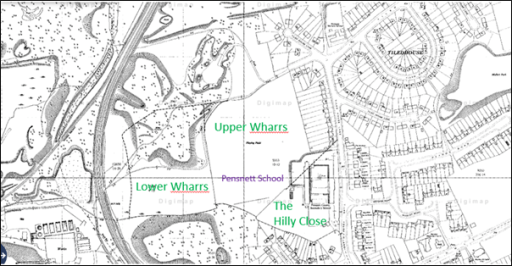

In our consideration of the life and times of Queen Edith, we see the emergence of much that contributes to our modern world, and many historical parallels and continuities. Our language is a direct descendent of the one of those that Edith spoke; our constitutional monarch is still a descendent of Cerdic; in the gathering of counsellors around the king on the Witan, we see a foreshadowing of our system of government; and the system of shire, shire reeves and shire courts that underpinned late Anglo-Saxon England, we see the foundations of our local government and legal systems. Indeed, the very existence of Rutland is due to it being Edith’s dower lands, and she has left her name in one of its villages. And shire reeves are of course still around. Despite these solid foundations, English society in Edith’s time was in a state of turbulence – divided by ethnicity, politics and language; threatened by external powers; at the mercy of the ambitions of powerful men, again foreshadowing something of current tensions in our own society and around the world. The life of Edith herself also evokes many modern issues some of which have a particular resonance for Mothering Sunday – the shame of childlessness, the struggles of an arranged marriage, the pain of loss of family and friends on the one hand and devotion to husband and adopted children on the other. And above all the simple struggle for a woman to survive in a male dominated society. And this is perhaps the most significant thing about Edith – she was a survivor – a woman who tried to hold things together as family and society were falling apart; something we see in the faces of women in refugee camps and war zones around the world.

But there is I would suggest a deeper continuity between Edith’s times and ours, one that is perhaps not obvious in our secular age where religion is largely seen as a private pastime, and spiritual experiences and realities dismissed. But in Queen Edith’s time that was not the case, and the spiritual was enmeshed in everyday life to a degree we would find hard to understand. Prof Richard North of University College London writes of the perceptions of the Anglo-Saxons in the pre-conversion era, with words that are equally applicable to Edith’s time, that spiritual realities

…were varied and widespread, and to the heathen mind in the early seventh, if not our own blind folly in the twentieth century, the world was charged with their power.

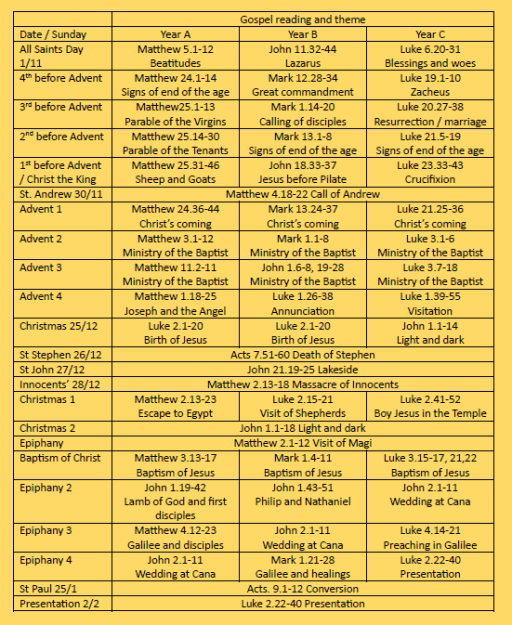

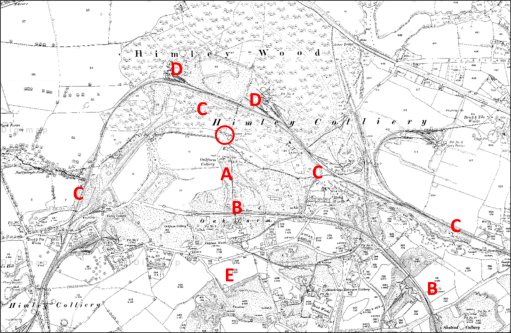

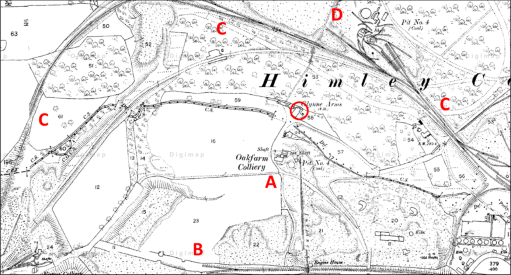

It is perhaps the rhythms of our worship that are a clock through which we can come to a deeper understanding of Edith’s times – as we go from Advent to Pentecost, from Lady Day to Michaelmas, we experience the unfolding of the scriptural and seasonal narratives with which those of Edith’s day would have been familiar, rhythms that would have constrained and ordered her life. She would have experienced the daily rhythm of the nunnery – the Magnificat sung in Latin at Vespers and the Nunc Dimittis at Compline. And further, whilst there can be no certainty, it seems to me highly likely that at some stage in her 20 years of marriage, Edith would have visited her dower land in Rutland, and we can imagine her in one of her manorial churches in Ridlington, Hambleton or Oakham, and can picture her participating in the mass or Eucharist that has been regularly celebrated down the centuries in these churches, with very few breaks – perhaps only in the interdict of King John’s Day, the turmoil of the Civil War, and most recently during the Covid lockdown. They were presided over by priest’s wearing very similar vestments to those used today – indeed when it was suggested we dress up as Anglo-Saxons at yesterday’s events, I thought about simply turning up wearing the Eucharist vestments! And the liturgy that she would have taken part in there would have been very similar indeed to the Eucharistic ceremonies of today – in Latin rather than English, but nonetheless essentially the same. God is praised, his saving work for the reconciliation of all things to himself is narrated, bread is broken, and wine is shared. I would suggest that it is in our worship that we can understand the rhythms of Edith’s time, and in which we find the deepest continuities between past and present.

And the Eucharist of course points to a yet deeper continuity, a longer thread, a thousand years before Edith – to Jesus and his disciples eating the Passover meal in Jerusalem just before his death and, three days later his resurrection. And that Passover celebration itself points to an even more remote time perhaps twelve hundred years before that, in a time and culture that for us would be utterly strange, as the people of Israel fled from Egypt to worship their God Yahweh, I am what I am, in the cloud and the fire on Sinai.

As Edith, with all her flaws and ambiguities, watched the mass in her Rutland churches, as we, being all too aware of our inadequacies, similarly eat the bread and drink the wine of the Eucharist here in Oakham, as we move in the rhythm of the year towards Lady Day, Good Friday and Easter, we become part of that long thread of history that takes us back to Sinai and Jerusalem, and to the England of a 1000 years ago, in which we join with all God’s children, alive and dead, the saintly and the not so saintly, and become part of the outworking of God’s plan for the salvation of the world.

It thus seems appropriate to end with words of praise to God – the words of the earliest known English hymn – that of the Northumbrian cowherd Cadmaeon from the late 7th century.

Nū scylun hergan hefaenrīcaes Uard,

metudæs maecti end his mōdgidanc,

Now we must praise – the protector of the heavenly kingdom

the might of the measurer – and his mind’s purpose,

the work of the glory father – as he for each of his wonders,

the eternal Lord – established a beginning.

He shaped first – for the sons of the earth

heaven as a roof – the holy maker;

then the middle-earth – mankind’s guardian,

the eternal Lord – made afterwards,

solid ground for men – the almighty Lord.