Introduction

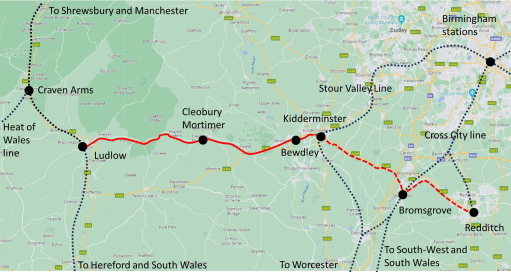

In mid-May 2025, I made a journey that I have had in mind for a number of years – a circular trip around North Wales mainly by inter-urban bus. I had a number of reasons for wanting to make this trip. Firstly it involves travel through some of the loveliest countryside anywhere in Britain. Secondly, it allowed me to indulge my obsession with looking at heritage railway stations, three of which are shown below – I will leave it to the reader to identify them. And thirdly, and for the purpose of this post most importantly, it allowed me to travel on the Traws Cymru bus network. I have watched this network develop from afar over the years, and have often thought I would like to look at it more closely.

In what follows I firstly describe the route that I took and comment on some general aspects. I then consider the vehicles that I travelled on, and then the infrastructure – bus stops and interchanges. Finally I make a number of comments on the good and bad points of the trip.

The route

The first step of my journey was to travel from my home in Oakham in Rutland to Ruabon on the Welsh border by train. This involved changes ta Birmingham New St and Shrewsbury. There were no problems either on the way there or the way out, with all journeys running close to time. At the start of the journey there was the perennial feeling of relief when it became clear my Cross Country train was really running and had not been cancelled, that turned into a feeling of surprise when it actually arrived at Oakham on time. But, as I say, the journey worked well and I arrived at Ruabon around noon as planned.

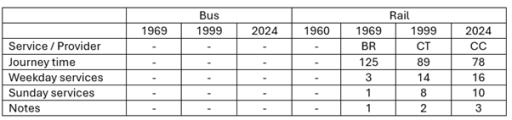

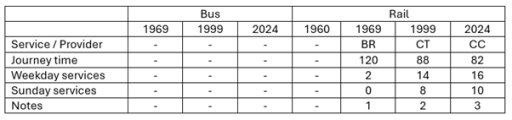

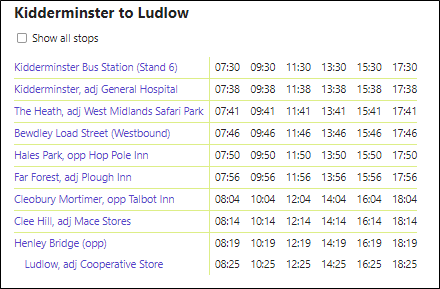

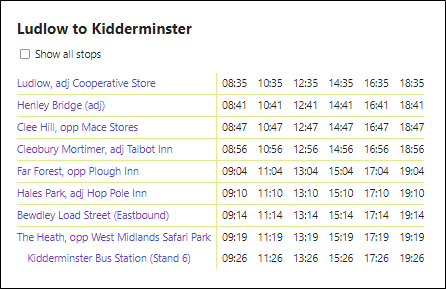

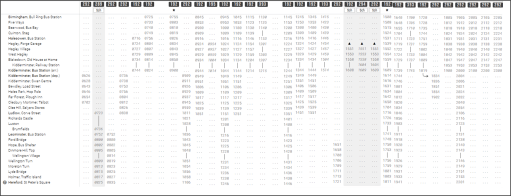

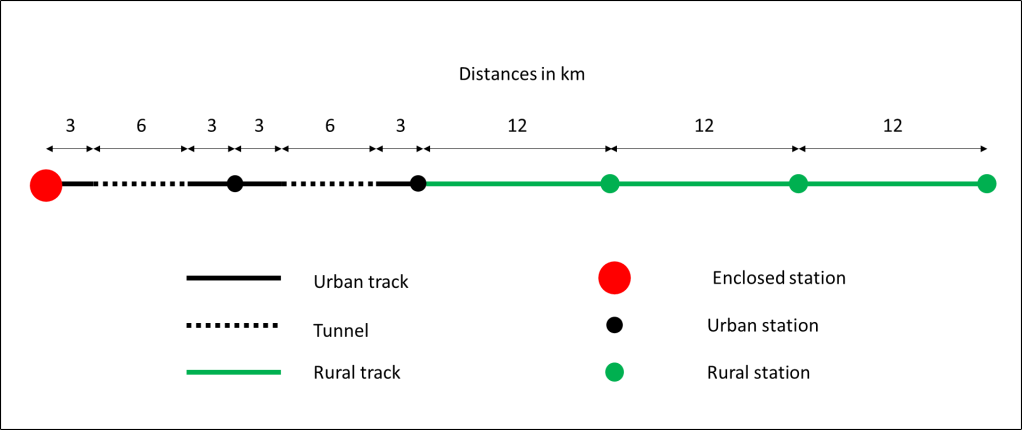

The Traws Cymru inter-urban bus network in North Wales is shown in the figure above. My first bus was not however part of the Trwas Cymru network, but rather the Arriva 5 from Wrexham to Llangollen that I boarded at Ruabon. I took this rather than wait an hour and a half for the first Traws Cymru T3 bus, and it gave me time for a brief look around Llangollen and a look at the railway station. On boarding this bus I asked for a concessionary 1bws ticket (£4.70 for all day travel on buses in North Wales for English bus pass holders – excellent value). The driver looked a bit mystified but eventually gave me the correct ticket. The bus was quite full – over 50% loaded – but fairly comfortable and made up some of the time after a 10 minute late departure from Ruabon. From then on my journeys were all (bar one) on the Traws Cymru network as follows (approximate loading given in brackets).

- Llandudno 13.39 to Corwen 14.04 – T3 (60%)

- Corwen 14.15 to Betws-y-Coed 15.03 – T10 (5%)

- Betws-y-Coed 15.05 to Caernarfon 16.23 – S1 (30 to 50%)

- Caernarfon 17.05 to Porthmadog 18.05 – T2 (100%+)

And the following day.

- Porthmadog 8.05 to Dolgellau 9.02 – T2 (30%)

- Dolgellau 9.03 to Bala 9.33 – T3 (5%)

- Bala 11.33 to Ruabon 12.39 – T3 (25%)

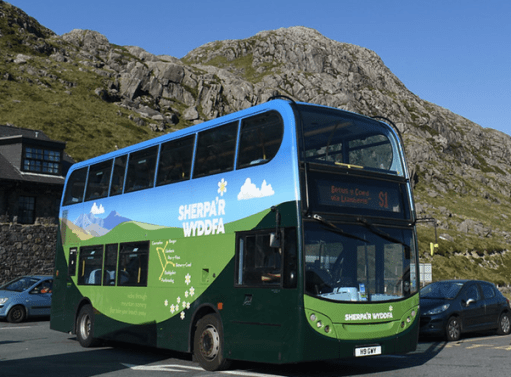

All the journeys kept time very well, and none was more than 3 or 4 minutes late at the point where I disembarked. Throughout the trip, the drivers were helpful and friendly, which makes a hige difference to the passenger experience. The journey not on the Traws Cymru network was the Sherpa S1. I chose to change onto this, rather than continue on the T10 to Bangor and catch the T2 to Caernarfon and Porthmadog there, simply because the ride up to Pen-y-Pass at the foot of Snowdon must be one of the most spectacular and exhilarating in the country.

The vehicles

I am by no means a bus expert, but from what I could gather from various websites, I travelled on the following vehicles.

- 5 – ADL Enviro400 City, operated by Arriva

- Traws Cymru T2 and T3 – Volvo B8RLE MCV Evora operated by Lloyds Coaches.

- Traws Cymru T10 – ADL Enviro200 MMC operated by K and P coaches.

- Sherpa S1 – ADL Enviro400 operated by Gwynfor coaches.

Photographs of all but the first of these are shown below

From my point of view as a passenger, the Traws Cymru and Sherpa vehicles were all basically buses – comfortable enough, with nice seats, but not of express coach standards. All vehicles had working USB charging points (something that many rail franchises don’t seem to be able to provide), and two of the Traws Cymru vehicles had WiFi, although this tended to drop out in the more rural areas. Most had screens that could potentially be passenger information screens, although they were not in use. As someone who isn’t terribly well acquainted with the area, the use of such screens to tell me which stop was coming next would have been really useful, and would have meant that I did not have to rely upon Google maps. In general though, I found the buses a pleasant and efficient way to travel, although I doubt I would have found them terribly comfortable for journeys of much more than an hour.

Bus stops and interchanges

Bus stops and interchanges are an integral part of any public transport journey, but in my experience receive far less attention and allocation of resources than they should. These feelings were reinforced on the journey described in this post

At Ruabon the Traws Cymru stop was just outside the station building. It contained basic information about timetables, but no real time information. The shelter was functional but nothing more. I actually only used this stop on my return journey – the Arriva 5 left from a stop at the end of the Station Drive. Here the same information (about northbound buses to Wrexham only) was being displayed in the shelters on either side of the road, which was confusing to say the least. If one didn’t have a basic grasp of the geography of the area, it would be easy to have got on the wrong bus.

At Llangollen I got off and on the bus at the Bridge Hotel stop. This can be seen to be a roadside stop of the most basic sort. Fortunately it wasn’t raining. There was a timetable displayed, but no real time running information.

Corwen was very different. Here there are proper interchange facilities with good, real time information, a solid shelter and space to wonder in the bus stop area. I think I could make out a toilet block too, but didn’t investigate it. This is a nice facility. It would probably benefit from not being branded as “Corwen Car Park” – although it is indeed in the centre of a car park. It is much better than such a name would suggest. My only worry would be that the shelter would not be large enough for all those changing vehicles on a wet day. But this is how it should be done.

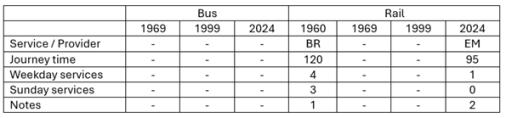

Betws-y-Coed is a strange place. It seems to be drowning in an ever expanding sea of car parks that have obliterated whatever it was that attracted folk there in the first place. The interchange is close to the station, and whilst there is shelter and some timetable information, I found the interchange, with four buses parking in an area that simply wasn’t large enough, very confusing and unsettling. Indeed I boarded the wrong bus at my first attempt. I think that there is scope for producing something like Corwen here, but it will cost I guess. Sadly the adjacent railway line, with its not-quite three hour interval service simply isn’t part of the interchange game here, which is based on a regular two hourly frequency.

Caernarfon bus station is simply a row of three of four bus stop and bays along a narrow street. However there is good passenger information and the provision of shelters is adequate. No problems here from my perspective.

I began my second day at the bus stop outside the Australia in Porthmadog. It is simply a roadside stop. Passenger information and creature comforts are minimal. Porthmadog deserves better.

With my trip almost over, it reached its low point – Eldon Square in Dolgellau. This was perhaps the most chaotic bus interchange I have ever experienced with four buses double parked in wholly inadequate, highly trafficked space. There may have been public information systems, but such was the chaos I couldn’t find anything. The place is simply not fit for purpose. It is clear from a web search that its inadequacy is well appreciated and there have been long term discussions about how to overcome the issues. Maybe something will be sorted out in future, but of all my memories of the trip, Eldon Square is the one that remains with me. I will do my utmost to avoid ever having to use it again.

My final change of buses was at Bala – simply alighting at the stop in the centre and getting on the next bus in two hours time. again, it was a simple roadside bus stop. with only a paper timetable provided, amongst a sea of notices pasted to the stop itself. Very oddly, one of these was advertising a vacancy for a clergyman in East Sussex!

Some closing thoughts

On balance I was quite impressed by the Traws Cymru network. The regularity and timekeeping were impressive (although I suspect the latter might suffer when the traffic is busier in the high season) and the tickets were excellent value. The buses were comfortable, at least for journeys up to an hour or a little longer. It would be good if more use could be made of the on board information screens, particularly for passengers who don’t know the area well. The bus stops and interchanges were not so impressive however, with only just tolerable information provision (and hardly any in real time) and shelter provision in most places. I suspect if the weather had been wet, I would have been less impressed by the experience. The contrast between my experience at the well thought out interchange at Corwen and the chaos of Eldon Square in Dolgellau was quite stark. Something really does need to be done about the latter.

A recent news item indicates that an express North / South Wales coach service is under consideration, over the route of the current T2 to Aberystwyth and the T1 from there to Carmarthen, which would only have a relatively small number of stops in the larger towns. From my perspective this is to be welcomed, but I would urge anyone involved in implementing such a scheme not to forget the passenger infrastructure where the coach calls. If a premium service is to be provided by high quality coaches, then this must be matched by higher quality passenger facilities at its calling points, with good quality shelter and information systems – and ideally toilets and access to refreshments. Good interchange with the rail network should also be provided, with something better than a bus stop in the station carpark, Without such provision I fear any such experiment will fail.