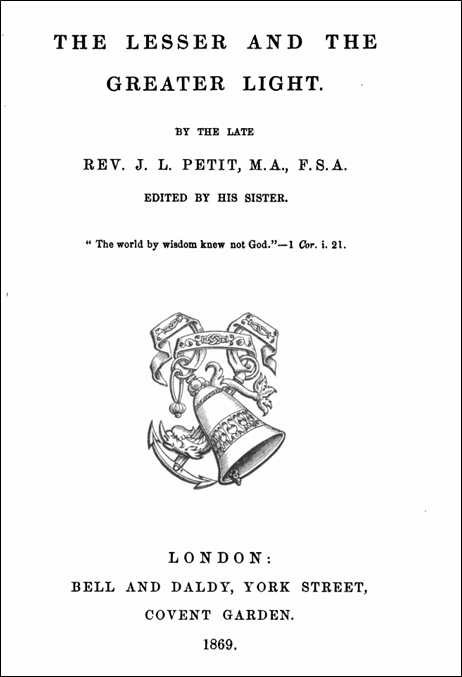

Introduction

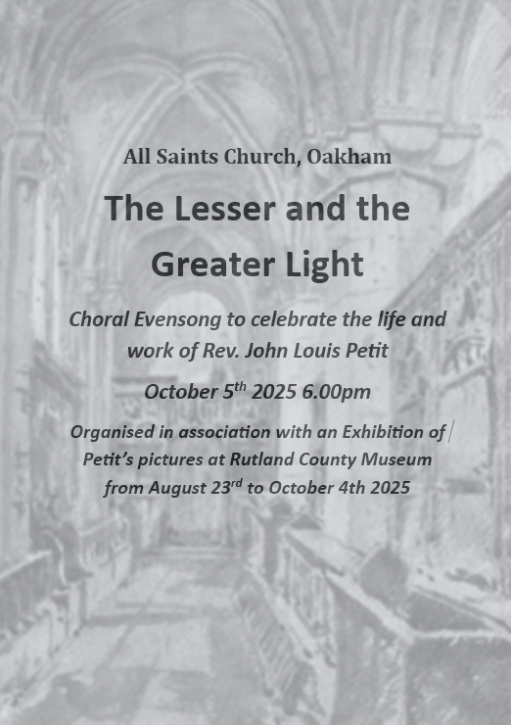

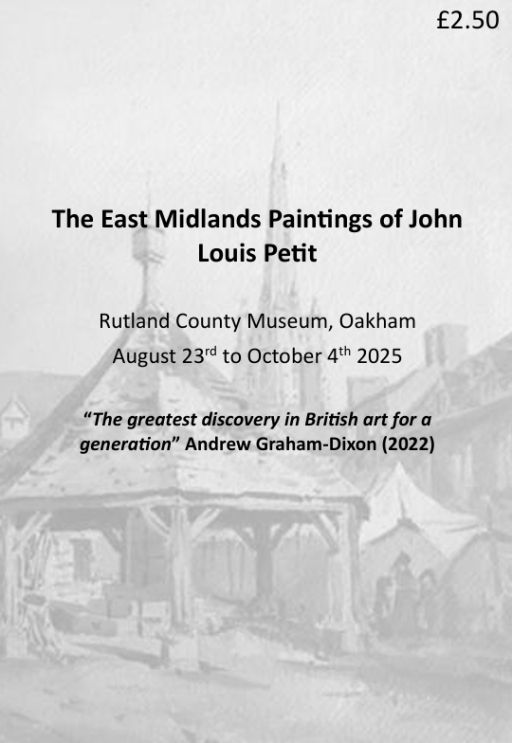

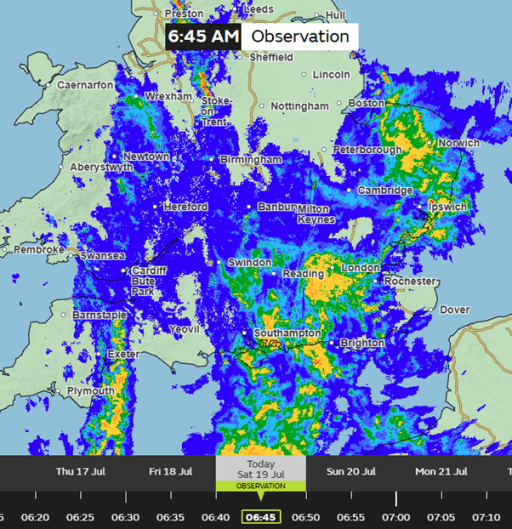

An Exhibition of the East Midlands paintings of John Louis Petit was held at Rutland County Museum from August to October 2025. During the preparation for that exhibition, I looked at whether the scenes that Petit painted were still recognisable today, and built up a collection of “then and now” photographs. Some of these have already appeared on various social media channels. In this post I show around 20 such comparisons and give brief notes as to locations and vantage points. Some of the modern photographs were taken by me, whist others were taken from publicly available sources. They are divided into the four sections used in the exhibition – Leicestershire and Rutland, Peterborough and Northamptonshire, Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire and Further Afield. I hope they will be of interest to some readers.

(Click on the pictures for full view versions)

Leicestershire and Rutland

St. Mary de Castro, Leicester – JLP 1845, Author 2025. The obvious difference between the 1845 and the modern picture is the lack of a spire- this was removed for safety reasons in 2013.

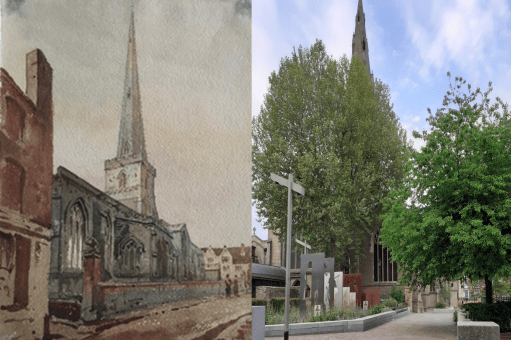

St Martin’s, Leicester – JLP 1845, Author 2025. St Martin’s became Leicester Cathedral in 1927 and has been considerably extended since Petit’s day, not least with the bones of Richard III. The 1845 view is now much obscured by trees and the new work.

St Luke’s, Thurnby – JLP 1845, Tim Glover, Creative Commons license. Petit painted his picture in the period in the period the church was without its chancel. The church was substantially rebuilt in 1870 by Slater and Carpenter with a new chancel and south aisle.

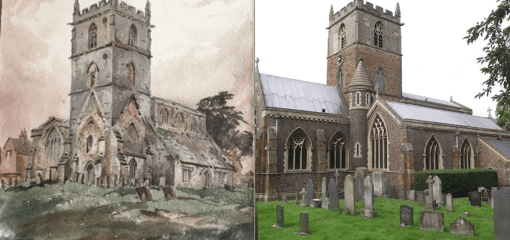

St Mary’s, Melton Mowbray – JLP 1850, Author 2025. Obtaining the modern picture required sitting on the ground at low level in a car park. One hopes the ground level was different in Petit’s day. There are some interesting differences between the pictures – specifically a door in the right hand aisle in Petit’s picture, and one in the left hand aisle in the modern picture – perhaps as a result of the restoration by Scott of the 1860s and 70s?

Kirby Muxloe Castle – JLP 1845, Ashley Dace 2010, Creative Commons license. The pictures are from very similar vantage points, and show little difference in the tower.

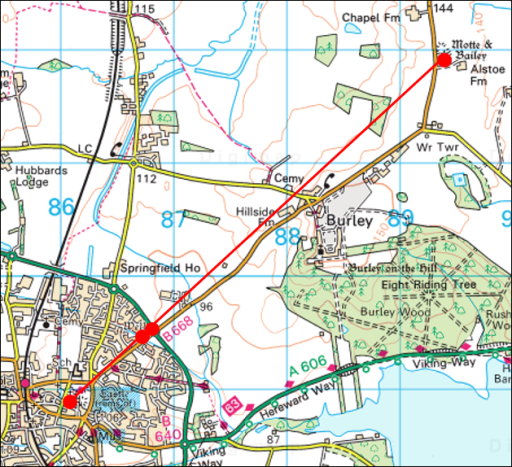

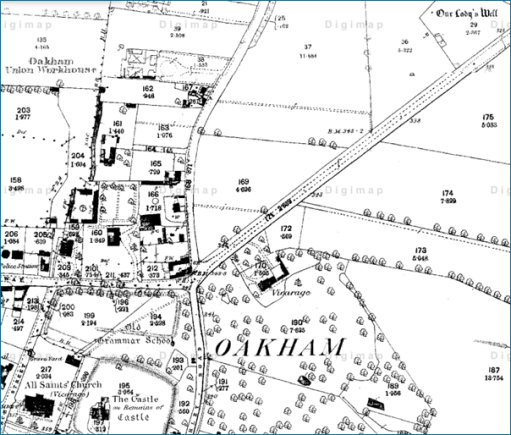

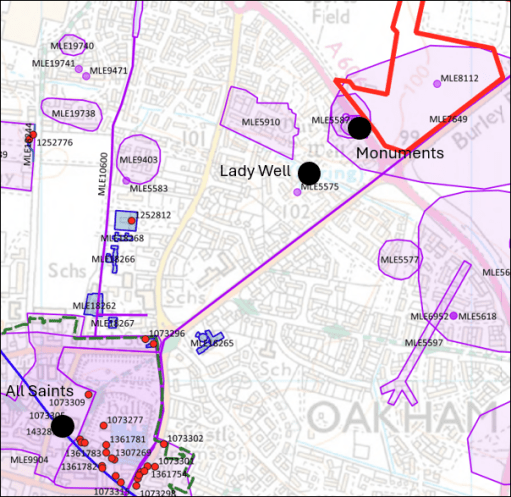

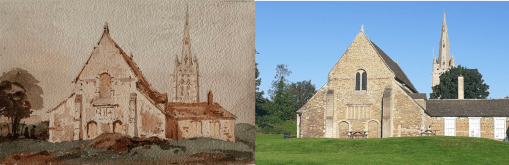

Oakham Castle and All Saints Church – JLP 1850, Author 2024. Both pictures are from the same vantage point. The major difference between them is the extent of the outbuilding on the right hand side.

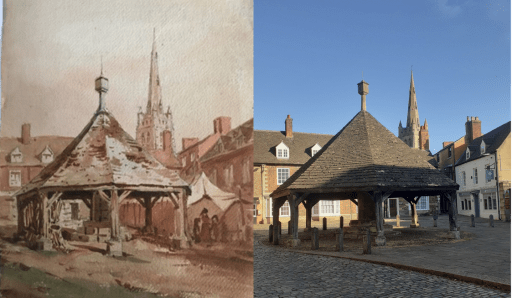

Oakahm Buttercross – JLP 1850, Author 2024. Again the pictures are from very similar, but not identical positions – the position from which Petit painted is now behind a hedge in the Oakham School grounds. The house roof lines and windows in the background are very similar. The building on the right hand side in 1850 has been replaced by the Sorting Office in the modern photograph.

St Peter and St Paul, Exton – JLP 1845, Author 2024. The locations of the two pictures are similar but not identical – to achieve Petit’s position would have required climbing over a fence and a boundary between the churchyard and the Exton Estate of the Gainsborough’s. The photograph was taken from very close to the church and significant perspepctive correction was required.

Peterborough and Northamptonshire

St Andrew’s, Northborough – JLP 1841, J Haywood, Creative Commons Licence 2025. The Petit line drawing is from his book “Remarks on Church Architecture” from 1841. The two views are very similar

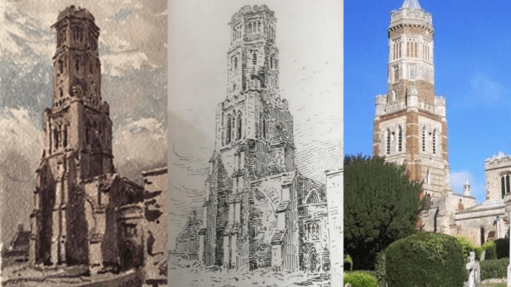

St Peter’s, Irthlinborough – JLP 1830,1841, Discover Northampton 2025. The line drawing is again from “Remarks on Church Architecture”, and was drawn for the 1830 painting. The tower in the modern picture shows the results from a major rebuild in the 1890s.

St Mary’s, Higham Ferrars – JLP 1830, Bearas 2024, Creative Commons license 2025. The major change here is to the chancel which was substantially rebuilt with a lower roof in the 19th century.

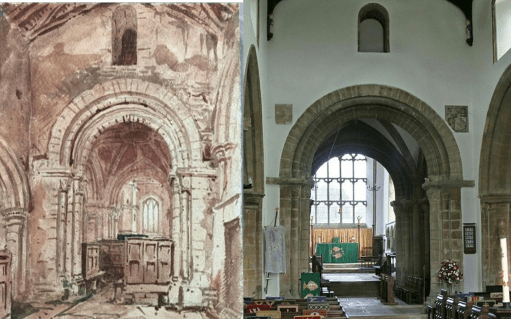

St Kynerburghia, Castor – JLP 1845, Alan Murray-Rust, Creative Commons license 2016. Both painting and photograph are from a position below the central tower. Petit’s painting shows a much more cluttered interior in the chancel area – possibly indicating an Elizabethan communion room arrangement.

Peterbrough Cathedral North Aisle – JLP 1845, Author 2024. The modern picture shows the location of the tomb of Catherine of Aragon. This was behind the screen that fills the aisle in the 1845 painting.

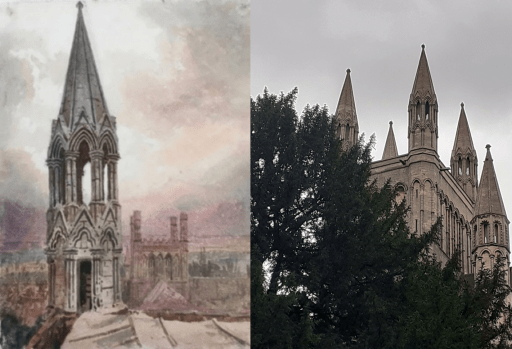

Peterborough Cathedral North Tower Pinnacle – JLP 1845, Author 2025. Petit painted the pinacle on the north tower from a location on the roof of the tower itself. It is looking east along the nave and chancel. I had neither the access or the inclination to get to the same vantage point, so the modern photo is from ground level, looking west from the side of the north aisle.

Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire

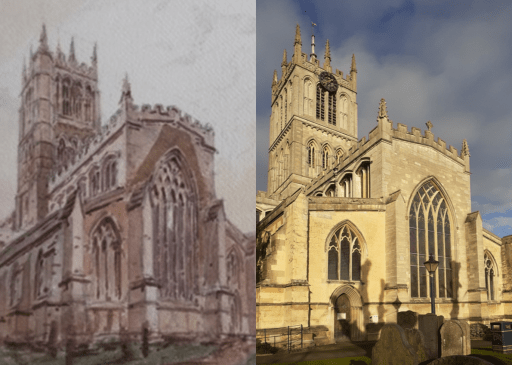

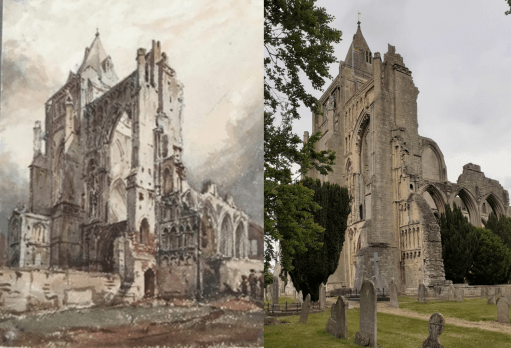

Crowland Abbey – JLP 1845, Author 2025. The location of the 1845 picture, possibly one of Petit’s most impressive, is now in the midst of a clump of trees, so the modern picture is from a slightly different location. The tree growth around the Abbey is significant.

South Kyme – JLP 1845, British Express 2025. The vantage points of both painting and photograph are very similar – and the tower has changed little in the interim.

St Peter and St Paul, Wisbech – JLP 1845, BBC 2023 (after Geograph/Richard Humphrey). Another case of significant tree growth obscuring the view that Petit painted.

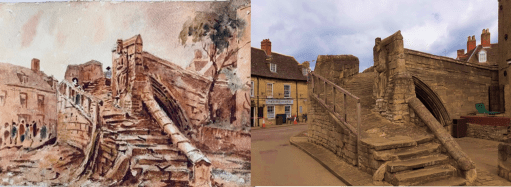

Crowland Trinity Bridge – JLP 1861, Author 2025. I managed to take the photo of Trinity Bridge in Crowland from almost the exact position from which Petit painted it and it can be seen the bridge is little changed. However Petit did not have to contend with cars and lorries wanting to occupy the same space.

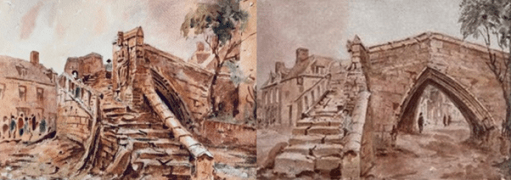

Crowland Trinity Bridge – JLP 1861 (x2). Finally I include a comparision of two pictures of Trinity Bridge in Crowland, almost certainly painted on the same day from slightly different vantage points. The right hand picture has recently been sold on eBay and is a screen shot from that site. The very similar representations of detail is astonishing, showing the accuracy of Petit’s representations.

Further afield

Both of these pictures are not really “then and now” – more “then and then” – and show the view that Petit painted against other historical views.

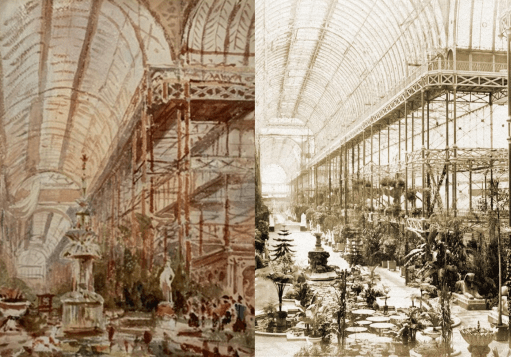

Crystal Palace – JLP 1867, Historic England 1859. The views are from similar vantage points, but show different exhibits in the same space. Comparing Petit’s painting of the superstructure with the photograph shows the accuracy of his representation.

Locmariaquer – JLP 1851, Postcard c 1900, Cartorum, Jules Coignet 1836, Public Domain. Petit painted his view of the dolmen at Locmariaquer in 1851. The painting by Jules Coignet is 15 years earlier, and the postcard view around half a century later. The similarities is in the rock formation in all three are striking, indicating again something of the accuracy with which Petit painted.

Closing Remarks

Perhaps the major point to emerge from this exercise for me is how Petit seems to have painted views from vantage points that were difficult to access, or from locations that most others would not have chosen. There are many churches for which I have not been able to make a comparison of Petit’s picture with the modern day situation, simply because there seem to be no published photographs from the location Petit used. He seems to have sought out the unusual viewing points.